“Transformative?” Not so much. New Pisgah Health Leader Talks Scaled-Back Plans

Previous spending and ongoing financial burdens have left Pisgah Health Foundation imagining a role much changed from when it was flush with the proceeds of the Mission Health sale.

BREVARD — Pisgah Health Foundation arrived on the local nonprofit scene in 2019 with a big bank account and big ambitions.

Formed after the sale of then-nonprofit Mission Health to industry giant HCA Healthcare Inc., it was funded with a pledge of $15 million over three years from the deal’s proceeds.

It not only started spending but spent money to tout its spending, producing a slick report in 2021, Relentless for Western North Carolina, that listed $5.5 million in grants distributed to area nonprofits in its first two years.

It paid $1 million annually over its first three years to a for-profit corporation for the controversial Brevard Blue Zones Project and, at one point, $183,000 in annual salary and benefits to former President Lex Green.

Not satisfied with its donated and newly renovated office near downtown, the Foundation agreed in 2021 to foot the bill to create its opulent Trust Center office and event space in a long-neglected old bank building on West Main Street.

Renovating the building, which it doesn’t own, ended up costing the Foundation $718,000 and saddling it with $8,950 in monthly rent, plus taxes and bills for insurance and maintenance, said Page Lemel, the chair of a new Foundation board installed at the end of last year.

Green said in an 2024 interview that he envisioned the Center as a downtown hub for regularly contributing “health insiders” and the half-dozen staffers he hired who would continue to raise money and otherwise fulfill the organization’s stated mission — “to seek transformative improvements in the health and well-being of all people in WNC.”

That’s probably not happening now, Lemel said.

The new board has been working to strip expenses, to shed the burden of the Trust Center lease and create a new role for the Foundation in the nonprofit community, which will definitely not be the same as it was at its founding — an accessible piggy bank for charitable organizations.

With diminished assets and a long list of financial commitments, the total sum available to nonprofits this fiscal year will be, at most, $160,000, she said in an interview on Monday.

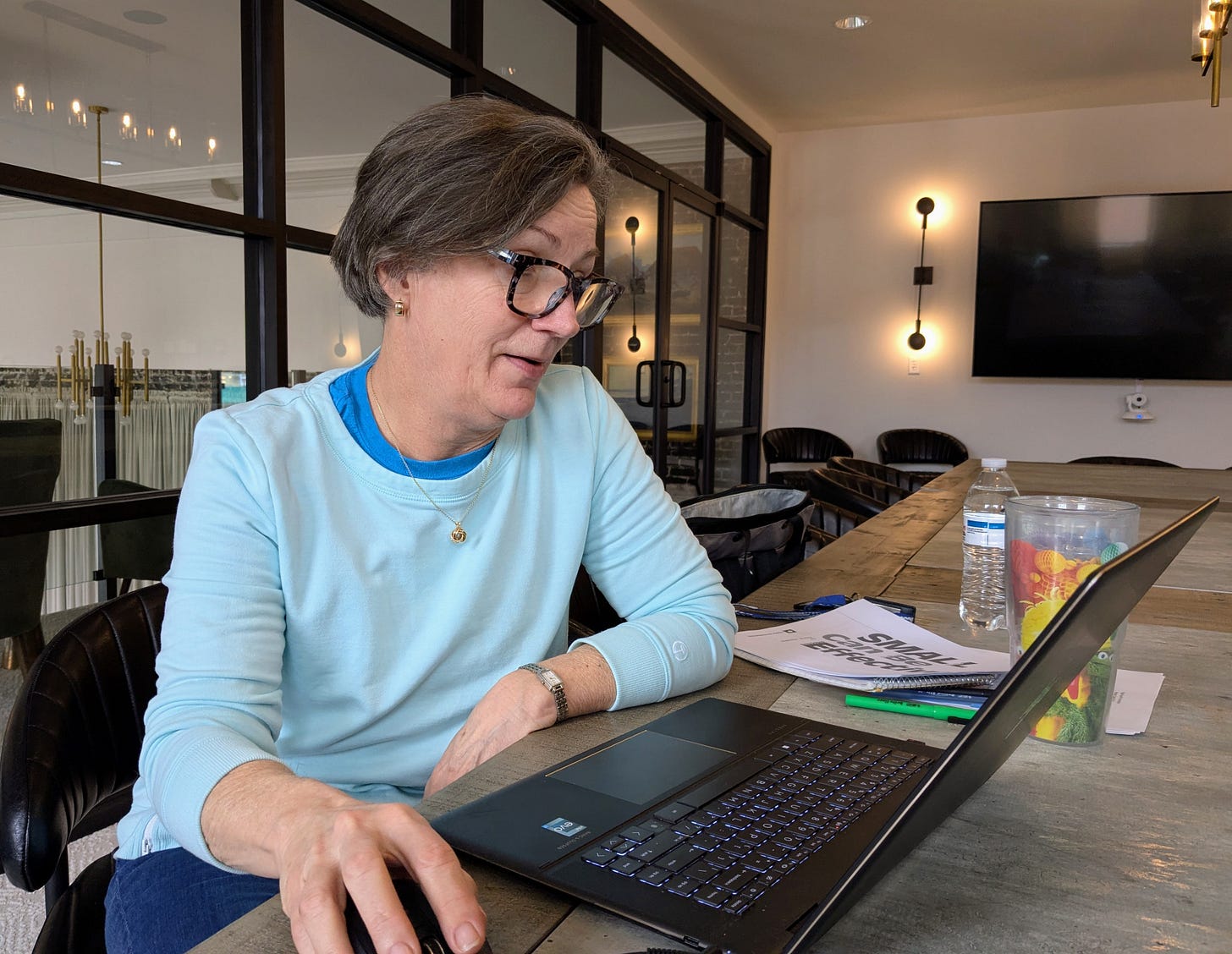

The group’s scaled-back ambitions were evident in the title of a guidance document for nonprofits resting next to her open laptop on a conference table at the Trust Center: “Small Can be Effective.”

They were also in her comments after she briefly took in the Center’s chandeliers, gleaming floors, puffy easy chairs and Persian-style area rugs.

“It’s stunning . . . an incredible building,” she said, “but it’s not where a little nonprofit needs to be operating.”

Shedding Burdens and Assets

Lemel, a longtime former Transylvania County Commissioner and owner of Keystone Camp for Girls, publicly questioned the Foundation’s decision to take on the Trust Center renovation after its completion in late 2023.

But she does credit the previous board for recognizing, last summer, that things needed to change.

It invited six potential new members to a meeting in July and hired an Asheville-based consultant to conduct a community survey about the work of the Foundation.

Though Lemel declined to provide a copy of the results, she said some commenters praised the restoration of the historic bank building, but many more criticized spending money for this work that should have been used to advance wellness.

Among the respondents’ descriptions of the Foundation board, she said, were “ ‘bombastic,’ ‘out-of-touch,’ ‘profligate’ and ‘uninvolved.’ ”

She also declined to provide details of how the new board came to power, and neither of the past two board chairs, Cathleen Blanchard and Jeremy Purcell, responded to requests for interviews.

But Lemel did say that five newcomers were voted in at the end of the year and that the board has since expanded to eight members.

Their first goal, Lemel said, has been identifying and stripping away unneeded expenses.

It has drastically cut the hours of its two remaining, formerly full-time staffers. It is working to eliminate inherited contracts with, for example, an information technology firm.

“Why are we paying $771 (a month) for IT services?” she asked rhetorically. “For what?”

It is hoping to find buyers for several taxable properties it owns in the county, she said, and has reached an agreement with the owner of the Center, John Nichols, to seek a new tenant for the building, the lease for which expires in June of 2026.

The long-term goal is to return to the Keeley House, on West Jordan Street, which was donated to Pisgah Health’s predecessor, the Transylvania Regional Hospital Foundation, in 2008 and restored to serve as the home of the new Foundation in 2019.

That office is currently being rented out. If it is unavailable when a new occupant is found for the Center, the current Foundation staff is so small, Lemel said, “that quite frankly, I think we could go virtual for a while.”

One other measure aimed at freeing up funds would mean, counterintuitively, giving up income-generating pots of money.

Of the organization’s roughly $15 million in total assets, about $5 million is held in “restricted endowments.” The income from these is legally designated for Pisgah Health operations such as Camp Bluebird, which hosts adult cancer survivors, and the Mission Belles nursing scholarship program.

But running these operations would require hiring more staff, Lemel said, and they could function more efficiently if the endowments were shifted — a long and legally complex process — to other nonprofits better equipped to take on these duties.

Mission Belles, for example, is a natural fit for the WNC Bridge Foundation, which already runs a robust healthcare scholarship program.

“It’s not costing Pisgah Health any value to get rid of those” dedicated endowments and programs, she said.

“In fact, it’s saving us money.”

Finding a New Role

Green said in a text response to questions about his spending that the organization’s mission was mandated by its founding documents.

It was a huge job, he said, and expensive.

“To achieve the tenets of that mission is a heavy lift financially,” he wrote. “As president, I took that mission very seriously and provided three years of robust grant writing, financial reporting (and) program development.”

He left the organization with roughly the same amount of assets it holds currently, $15.1 million.

Which means that compared to the average holdings of nonprofits in the country, it is far from small.

“PHF probably has very robust financial assets compared to the majority (of nonprofits) in the US and in Transylvania County,” he wrote.

That’s true in one sense, Lemel said, but Pisgah Health isn’t flush enough to be a major source of money for nonprofits in the near future, especially given the limits on the use of its assets and capacity to raise funds.

Only $10 million of its endowment is unrestricted, and in an effort to preserve that nest egg, the board “is maintaining a 5 percent spend rate,” according to a statement the Foundation released last month, leaving an annual budget of “approximately $500,000.”

The $160,000 for charitable organizations is the maximum amount that will remain from that sum after subtracting salaries, service contracts, rent on the Center and other burdens, she said; it also depends on the health of financial markets.

The board has scrapped the Foundation’s original plan of generating revenue by renting the Center out for weddings and other private events at costs as high as $2,750.

For one thing, it didn’t have many takers, Lemel said, partly because of lingering ill will about the money spent on the project.

“I think that caused the community to react so negatively that nobody wanted to use the building,” she said.

And embarking on an aggressive fundraising campaign, as Green envisioned, would put Pisgah Health in the counterproductive position of competing with the nonprofits it seeks to support for the limited resources in its service area — primarily Transylvania, but also Haywood and Madison counties.

“We don’t have a sugar daddy, a big corporation that can stroke us a million-dollar check,” Lemel said.

Still, the challenges to the Foundation remain the same, addressing dire shortages of affordable housing and mental health care and other obstacles to community well-being.

How can the Foundation do that with limited resources?

Cutting costs will free up more money to distribute to area nonprofits in the coming years, Lemel said, and the Foundation might also take on one of the roles of the former United Way of Transylvania County, which ceased operations in 2020.

It could serve as the “trusted organization” to manage and distribute large donations, such as grants from other foundations and bequests left in wills, she said.

“Maybe Pisgah Health could be the repository.”

But it has already started filling one other role, serving as a coordinator for area nonprofits, or, in Lemel’s words, “a convener.”

That started with making the Center easily accessible as a meeting and event space for nonprofits. These groups can now use the upstairs conference room and the downstairs ballroom for up to four hours at no cost and full days for $25 and $75 respectively.

That coordination role was also on display on Monday, as was the help Pisgah Health could offer nonprofits seeking grants.

Just before Lemel sat down for the interview, she met with members of the newly formed Transylvania County Long-Term Recovery Group, which seeks to remediate damage from Tropical Storm Helene and improve preparedness for future disasters.

The Group is not yet registered as a nonprofit and needed help in applying for a large grant from the American Red Cross “to get this off the ground,” said Cara Bradshaw, the Long-Term Recovery chair.

Pisgah Health, as an established nonprofit, has agreed to partner with the Group to apply for the grant, Bradshaw said.

She emerged from the meeting with the hope the Foundation might also be able to help nonprofits tap into other large funding sources, and with good feeling about the new board.

“With the new leadership, and the confidence in that new leadership — that’s a big win for Transylvania County,” she said.

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Sounds like an organization that was having great initial impact and is now doing less work other than “saving money”. I wonder how a health foundation can improve the health and wellness of local folks by guarding a “nest egg” of $10 million? Wasn’t that money supposed to be used to help local non profits? Money in the bank only helps the board controlling the purse strings.

A few years ago this organization was awarding local students nurses scholarships, hosting cancer survivor camps, having healthy cooking classes for all public school district chefs, setting up student wellness committees in every TC school, improving local worksites for the benefit of local employees, having health workshops, hosting athletic events, establishing Covid drive through testing that helped 5000 people, giving out vital medical supplies, working to improve physicians burnout to retain local doctors, supporting front line workers, funding the needs of many local non profits to ensure they did not close their doors, funding food boxes for the homeless, trying to keep the adult day care facility open, funding elderly home repairs, advocating for the Ecusta trail, and addressing affordable housing. They were a certified living wage employer and were recognized by the state of NC for helping seniors in need. Why did that all end? A few years ago it seemed all the non profits were grateful for their help and local citizens that participated in their programs were very happy. The physicians liked them. They had lots of good things going on. Sounds like a loss for the community. I hope they get their groove back.

Thanks Dan. Sounds like a failure. Another government program that went nowhere

Where was DOGE when we needed them ?