The $3 Million Brevard Blue Zones Project: A Mix of Real Benefits and Marketing Claims

Residents praise Blue Zones' goal of improving public health and the impact of some of its programs. But critics say it exaggerates accomplishments and uses misleading metrics.

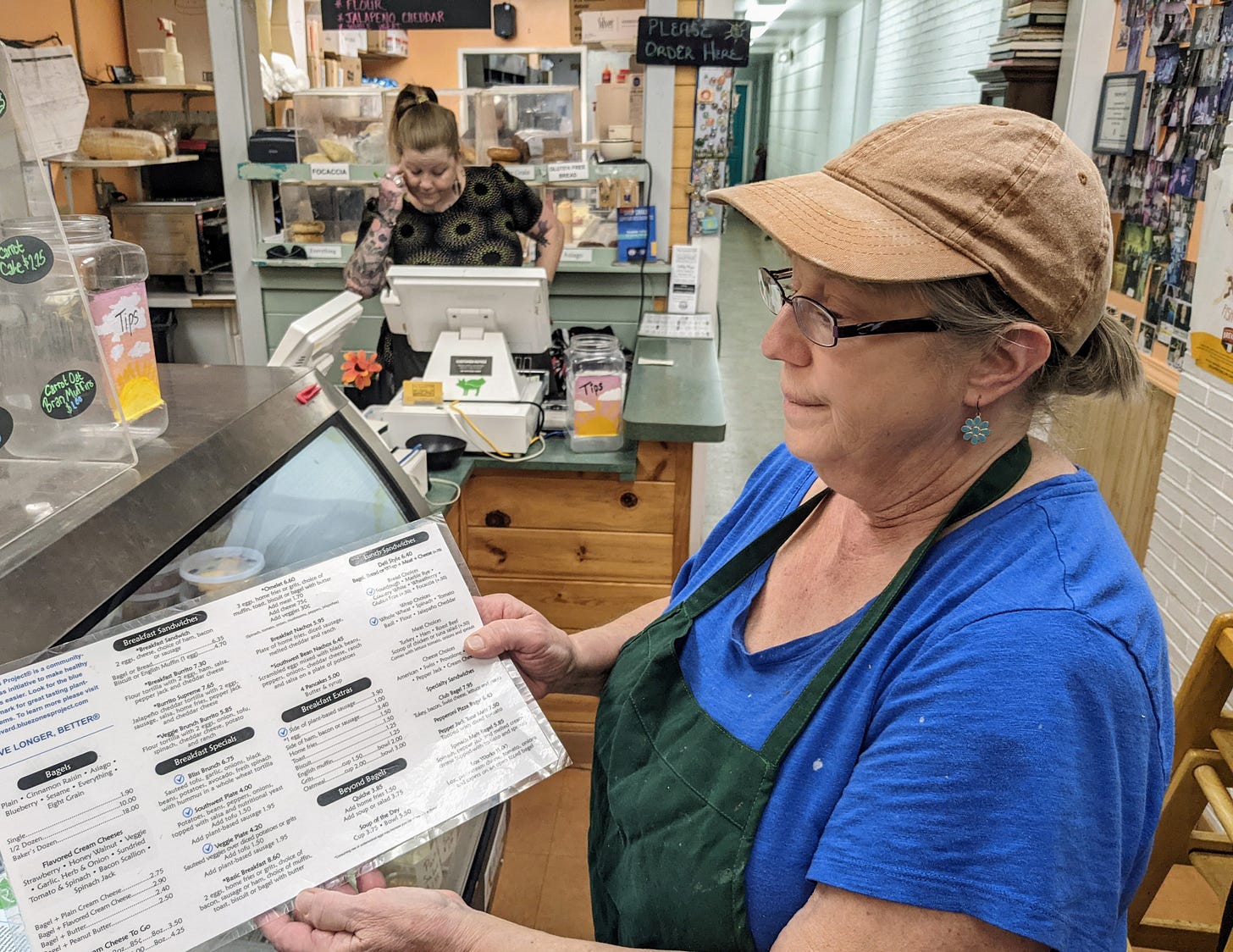

BREVARD — A chalkboard high on a wall at the Sunrise Cafe lists a half-dozen “Blue Zones Menu Items,” including a Bliss Brunch of black beans, tofu, avocado and spinach.

Blue checkmarks highlight more such offerings on the Cafe’s printed menu. And as proof that they are catching on, owner Marisa Gariglio said she whips up twice as much hummus as she did before the popular breakfast-and-lunch spot near Brevard College became a Blue Zones-approved restaurant last year.

“We still sell more bacon than anything in the world. That doesn’t stop,” she said. “But I do think we’ve given more choice to those who are vegetarians.”

It’s progress, in other words, one sign among many that the Brevard Blue Zones Project has reached “a tipping point where we can continue to sustain and grow the work,” said Senior Program Manager Sarah Hankey, a local employee of Sharecare Inc., the for-profit company that runs Blue Zones in Brevard.

The Project, like dozens of others across the country, aims to improve community health and well-being by encouraging changes to policy, infrastructure and residents’ diet and exercise habits.

Blue Zones’ three-year-plus run in Brevard — funded by a total of $3 million in payments to Sharecare from the nonprofit Pisgah Health Foundation — comes to an end this month. But it will leave a lasting certification of Brevard as the state’s first Blue Zones Community, a Project press release said, a recognition “of Brevard’s well-being transformation through the successful implementation of the Blue Zones Project.”

But what does this transformation look like? What did the community get for this money?

Blue Zones’ goals of promoting regular physical activity, social cohesion and wholesome eating are certainly admirable, the more than two dozen people interviewed for this story agreed.

Few of them doubt that Blue Zones programs — including walking groups, cooking classes and initiatives in more than 70 schools, businesses and public agencies — have nudged residents to make healthier choices.

Locals also use words like “great” and “awesome” to describe the Brevard Project’s three staffers and singled out Hankey for her work in addressing the ongoing youth mental health crisis.

But there’s also this: Blue Zones is a brand designed to generate revenue.

It’s used by Sharecare and — though he’s no longer involved with the community projects — author Dan Buettner, who trademarked the name and continues to feature it in the titles of his popular cookbooks.

And it’s been advanced by Sharecare’s assertions of sweeping benefits, many of which are questioned by local and out-of-town critics.

City Council members recently pushed back on Blue Zones’ claimed role in improving and planning what the Sharecare calls “the built environment” — parks, trails and policy documents intended to bring residents together and promote physical activity. In fact, members say, the Council’s been pushing these initiatives for years and the real work was done by city staffers and consultants.

A close examination of public data supporting some of Sharecare’s claims show the company’s use of this information can be selective and misleading — and that by some measures and in some cases community health has declined after Blue Zones’ arrival.

Even more suspect, according to public health experts, are the Projects’ numbers generated by its own surveys.

Blue Zones “pretend that they are in the scientific research domain, but they are really more in the marketing domain,” said Eric D. Carter, a professor of geography and global health at Minnesota’s Macalester College.

“To me it’s just a lot of mumbo-jumbo.”

Pisgah Health

Blue Zones projects operate “as a partnership between Sharecare Inc. and Blue Zones LLC,” Jen Martin Hall, Sharecare’s executive vice president of corporate communications, wrote in an email.

Buettner formed the LLC, which owns the Blue Zones copyright, in 2005 and sold it to nonprofit Adventist Health in 2020.

Sharecare Inc., an Atlanta-based health-and-wellness corporation, was founded in 2010 by current CEO Jeff Arnold and controversial doctor and former unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate Mehmet Oz, who is no longer affiliated with the company, Hall said.

Lex Green, the former executive director of Pisgah Health, said in a Youtube video that he was inspired to bring Blue Zones to Brevard after learning about the concept from his son, who had read one of Buettner’s books.

It was about this time that the Foundation was facing big changes.

Originally established as a fundraising group and previously called the Transylvania Regional Hospital Foundation, it got its new name in 2019, along with a new mission — to promote community health — and the promise of a new funding source: $15 million paid out over three years from the proceeds of the sale of nonprofit Mission Health — the previous owner of the local hospital — to for-profit HCA Healthcare.

“That is our money, from our hospital, that is in that fund,” said Brevard Mayor Maureen Copelof, who is generally supportive of Blue Zones.

Green, who left his job at the Foundation in September, declined to comment for this story, and Pisgah Health’s interim executive director, Shiela Jarvis, wrote in an email that the Blue Zones contract between the Foundation and Sharecare was “not available.” Neither, she wrote, were the organization’s most recent budget nor minutes of Board meetings where the Sharecare contract was discussed.

But Jarvis did confirm figures from the group’s publicly available tax returns including:

Green’s total compensation in 2021, including benefits — $183,584.

The Foundation’s reserves at the end of that year, about $12 million, accrued from earlier community donations, estate grants and the payments from the proceeds of the Mission sale.

The $1 million annually paid to Sharecare, which in 2021 exceeded the $785,000 total of all other contributions and dwarfed individual grants to regional nonprofits that ranged from less than $10,000 to a maximum of $50,000.

Pisgah Health Board Chair Cathleen Blanchard, while acknowledging that the Board approved the Sharecare deal, described it as mostly Green’s doing.

“The board was led by Lex and he is the one who brought Blue Zones here,” she said, “and so we’re going to credit him with being instrumental in bringing it here to Transylvania County on a three-year contract.”

The Origin Story

Why Blue Zones?

Because, Buettner said in an interview, it represents one of the few viable options for holding back the ever-rising tide of temptation created by American food and transportation networks — the ubiquitous offerings of fast food and sugary snacks, the street layouts that invite us to reflexively jump behind the wheel of a car.

Because people are “genetically hard-wired” to seek both ease and calorie-dense foods, he said, communities can’t just advocate for better eating and exercise habits. They need to “reshape environments,” he said, and the difficulty of this task should be considered when examining his work.

This started after researchers documented a disproportionately high incidence of centenarians on the Italian island of Sardinia in the 1990s. Buettner and a team of demographers went on to identify four other regions of exceptional health and longevity in Costa Rica, Greece, Japan and California — work Buettner wrote about in a 2005 National Geographic cover story.

Buettner and his team, according to the LLC’s bluezones.com, “set out to reverse-engineer longevity,” identifying common habits of these blue zones’ inhabitants such as consuming mostly plant-based foods, engaging in regular physical activity and living purposeful lives shared with other members of close-knit social circles. It then began the work of spreading these practices to American communities.

But what if the very old people in these zones aren’t really that old?

Saul Newman, a demographic researcher at England’s Oxford University, doesn’t doubt that Buettner and his team used the best available birth and death records and took pains to validate them. He just thinks these documents are likely skewed by undetectable errors and the powerful incentive to exaggerate age.

After a high-profile 2010 case of pension fraud in Japan, for example, the country launched an audit of its demographic records that found 230,000 residents previously reported as centenarians were “unaccounted for.” A similar 2012 examination in Greece — home of another designated blue zone — also found widespread irregularities in the claims of pension recipients.

In 2019, Newman published a pre-print on an academic website saying blue zones such as Sardinia and the Japanese island of Okinawa are also poor regions with low overall life expectancy compared to their countries as a whole. He called such factors unlikely “predictors of centenarian and supercentenarian (110-plus) status, and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records.”

Buettner responded to this criticism on bluezones.com, and in an email to NewsBeat wrote that poverty can result in longer and healthier lives if it leads people to walk more, eat cheap-but-healthy foods such as beans and avoid heart ailments and other “diseases of affluence” that kill so many Americans.

Buettner added that it’s the loss of frugality and self-sufficiency in the past two decades that accounts for some of the more recent statistics Newman cited, such as the high obesity rate in Okinawa.

Buettner relied on the work of “top-tier demographers,” to support his findings, he said in his interview. In Okinawa, for example, researchers included a geriatrician who has lived on the island for decades and “actually works in all these villages and treats all these centenarians,” Buettner said, and in the Costa Rican zone “our team went and saw . . . every single (living) centenarian.”

Their articles have repeatedly appeared in peer-reviewed journals, while Newman’s analysis — written when he was working as a plant geneticist in Australia — has never been accepted by such publications.

“I spent eight years of my life making sure I did this right,” Buettner said of the research. “Saul (Newman) never set food in a blue zone.”

Commercial Pressure

Newman told NewsBeat he stands by his post and in a 2021 interview with the Sydney (Aus.) Morning Herald’s national science reporter, he colorfully dismissed Buettner’s response as “basically what you’d expect if you told the yeti-hunting society that yetis don’t exist.”

Other demographers support Buettner’s arguments about the strength of the research behind blue zones. But they also raised concerns about the commercialism of the concept.

Robert D. Young, a demographer for the independent Gerontology Research Group and a consultant on old-age claims for the Guinness Book of World Records, described Newman a self-promoter and “over-skeptic” of centenarian data.

“But a lot of the Blue Zones stuff is marketing material that is not solid either,” Young said, and demographics similar to Sardinia’s can be found in many other coastal Mediterranean communities.

“The idea that a blue zone is some magical little place that is isolated from everywhere else is not true,” he said.

Michel Poulain, one of the researchers who helped identify original blue zones, said in an interview from his home in Belgium that he stands firmly behind their designation and calls Buettner’s work to spread healthy habits in the United States “the most valuable thing he did.”

But Poulain also said that Buettner “made a lot of money on something that I produced 20 years ago.”

Buettner wrote in an email that, in fact, another researcher coined the name. He called Poulain “a great demographer” but added that the two of them haven’t worked together directly for about two decades.

Buettner also said that, since the sale of the LLC, “I have nothing to do with” Blue Zones projects.

He continues, however, to use the name in cookbooks such as the best-selling “The Blue Zones Kitchen: 100 Recipes to Live to 100.” And, Poulain said, “He is putting all his effort on food because that is the component he can make the maximum amount of money on.”

As an example of the pressure commercial interests can apply to research, Poulain said Buettner recently asked him to identify additional longevity zones in countries with highly marketable cuisines — India, Mexico and Thailand.

“I said I cannot because there is no data,” Poulain said.

Buettner wrote that “in the scope of things, (the books) are irrelevant money-makers for me.”

In his interview, he described his conviction about the harm caused by the American “food environment” and his determination to create healthy-but-appealing alternatives. He hoped to further this goal by developing recipes in the countries Poulain mentioned, calling them in an email the “cuisines that Americans love best.”

“I reached out to (Poulain) for some ideas” Buettner wrote. “I had no intention to name them Blue Zones . . . and for the record, I’m likely taking a different tack for the book.”

Ground Zero, Then and Now

If there’s a poster-child for the benefits of Buettner’s ideas, it is Albert Lea, Minn., where in 2009 Blue Zones LLC launched a “pilot project” that is still up and running.

It helped spark a virtual renaissance in the town and surrounding Freeborn County that features prominently in Blue Zones literature. There are now bike paths, a walkable downtown and a completely renovated park in Albert Lea, according to the LLC’s website. The city has seen robust business investments, multi-million-dollar savings in health care costs and big improvements in community health.

The number of adult smokers dropped from 23 percent in 2009 to 14.7 percent in 2016, according to the website. And text on the web pages of several local projects, says the county “jumped up 34 places in the Minnesota County Health Rankings,” and “after just one year, participants (in Albert Lea) added nearly 2.9 years to their average lifespan.”

The pages also quote a professor at Harvard University’s school of public health, who called the results “stunning.”

They appear less so, however, after the sources of the statistics are examined closely and publicly available numbers are tracked over the full length of the Project’s run.

Sharecare uses several sources of data to determine projects’ benefits, said Hall, the Sharecare communications executive. Primary among them is the company’s Community Well-Being Index (CWBI), based on surveys of residents about a range of “physical and social factors,” according to the company’s website.

The reported lifespan gain in Albert Lea came from Blue Zones LLC’s True Vitality Test, which estimates individual life expectancy based on answers to questions about, for example, consumption of healthy foods and frequency of exercise.

Both tools were developed with the advice of outside experts, including, in the case of the CWBI, initially the Gallup polling company and, more recently, researchers at Boston University.

Even so, “measures of self-reported health are intrinsically problematic, for being subjective,” said Carter, of Macalester College, who published a 2015 paper examining the political ideology behind the use of private Blue Zones projects to advance the public goal of improving community health.

Also, Carter said, such tools’ ownership by the companies behind the Blue Zones projects “means there is a conflict of interest . . . it would be better if a neutral third party, not attached financially to the BZP, conducted the survey.”

Blue Zones’ literature does cite data from such third-party sources, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s rankings of counties’ public health.

The baseline numbers, taken from the site near the start of the Project’s run, match statements from Sharecare and the LLC, as do some results recorded midway through its time in Albert Lea.

Freeborn — where Albert Lea is the dominant population center — was ranked 68th of 87 Minnesota counties for overall public health in 2011, according to the Foundation. (Though that was the earliest information available on the site, it typically relies on data about two years old.)

Twenty-three percent of adults were smokers and 28 percent were “obese,” according to a table on the Foundation’s site. A new measure added the following year applies to Blue Zones’ goal of encouraging exercise: 23 percent of adults reported “no leisure-time physical activity.”

By 2018, according to the Foundation, Freeborn had indeed climbed 34 places in the statewide health rankings, to 34th, and its percentage of adult smokers had dropped to 16 percent.

But by 2022, according to the Robert Wood Johnson site, the reported gains were less dramatic and some markers indicated recent declines in the county’s public health.

Freeborn’s ranking had slipped back to 55th in 2022, according to the site, and its rate of smokers had climbed since 2018 to 19 percent — four percent lower than in 2011, but higher than in the state or nation as a whole.

The 35-percent obesity rate reported by Robert Wood Johnson in 2022 was 5 percent higher than the statewide figure and 7 percent higher than that of Freeborn in 2011.

Finally, the Foundation data showed that during the previous decade — a time of robust, Blue Zones-inspired trail and park construction — the prevalence of physically inactive adults in 2022 had climbed in the past decade to 27 percent — also above state and national rates.

Brevard Results

In Brevard, the reported health gains since Blue Zones’ arrival include:

“The number of residents suffering from high cholesterol is down 61.7 percent,” the certification press release said, while “tobacco use is down to 5.4 percent of adults, well below the state average.”

These results are based on the CWBI, while the company cited the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as the source of the statement that “life expectancy increased in Transylvania County from 80.2 years in 2020 to 81 years in 2022.”

That’s true enough, according to the site, but it also clearly states those figure were based on data collected in 2019, before the full launch of the Brevard Blue Zones Project.

The numbers generated from Sharecare surveys, meanwhile, clashed markedly with those in the most recently available public source, Transylvania’s 2021 Community Health Assessment, which was based on reports from randomly selected county residents in the middle of that year — about halfway through Blue Zones’ stint in Brevard.

The Project’s reported finding of a dramatic drop in high-cholesterol levels came from surveys showing more than 17 percent of respondents reported this condition in 2020 compared to less than 7 percent in 2022.

The Assessment also showed a significant decline, but from 35.8 percent to 25.1 percent.

The prevalence of adult smokers in the county, meanwhile, dipped only slightly to 13.7 percent, the Assessment found, or about 8 percent higher than the rate reported by Blue Zones.

As for other measures of public health in the Assessment, the prevalence of overweight and inactive adults was on the upswing in 2021, while consumption of healthy foods was heading down.

The number of adults who reported “no leisure-time physical activity in the past month” had climbed slightly since 2018 to 20.2 percent in 2021, and Transylvania’s rate of obese and overweight adults stood at 70.6 percent — nearly 13 percent higher than in 2018, and higher than the rate in the region, state or nation.

The number of people who consumed at least five daily servings of fruits and vegetables, meanwhile, plunged over that same period from 13.5 percent to 6.4 percent.

The results of the Assessment are not definitive, the explanation of its collection methods says: because it is also based on surveys of a relatively small number of residents — 223 in 2021 — the findings come with a significant margin of error.

And some of the difference between this source and the Sharecare surveys can be explained by the different populations measured, Hankey said. The assessment’s surveys are conducted countywide, while the Brevard Blue Zone Project is confined to the 28712 area code that includes the city and much of central and southern Transylvania.

But the results also show the Project has failed to reach the broader community, said Brevard City Council member Geraldine Dinkins.

Most residents who engage with Blue Zones “already appreciate the outdoors, eat their veggies and have the time to seek communal experiences,” she wrote in an email, and their reports can be “shined up to portray all kinds of positive yet surprisingly vague metrics.”

Policy, Streets and Parks

What about another crucial aim of all Blue Zones projects — redesigning communities so that, as in their namesake regions, activities such as walking and gardening become part of everyday life?

The local accomplishments in this regard are impressive, Hall wrote in her email, which said “$3.8 million in grant funding was leveraged with Blue Zones Project support, including grants for the Ecusta Trail, City of Brevard Community Garden, and school gardens.”

She also highlighted streetscaping, tree planting and extensive park construction, as well as job creation that resulted from the expansion or renovation of downtown enterprises and “the 24 businesses that opened.”

Mark Burrows, the former Transylvania County planning and economic development director who led the local Blue Zones Project until temporarily moving to Norway last year, provided more details of Blue Zones’ contributions to Brevard’s infrastructure and planning.

The Project steering committee “devoted a great deal of time and energy” to address the city’s dire shortage of affordable housing, he wrote, and compiled a report “presented, at the city’s request, during a special workshop devoted to this topic.”

Blue Zones identified the Ecusta as its “marquee project,” he continued, and the group wrote letters of support for grants while volunteers spent hours identifying potential trail heads.

The group brought in a well-known street-planning expert and worked with the city and state Department of Transportation to design safer downtown intersections, Burrows wrote, and he personally advised city staffers on the creation of an updated Comprehensive Land Use Plan.

But he was also careful to say that his involvement with that process lessened after the city hired a consultant to write the plan. And when it comes to the Ecusta, he said, “the main credit” for progress on the trail belongs to the city and groups including Conserving Carolina.

Hall, meanwhile, didn’t claim the Blue Zones Project was directly responsible for the planning and building efforts she listed in her email, instead saying they were part of a larger community effort and labeling them as “outcomes since launching the local Blue Zones Project.”

Longtime Council member Mac Morrow, who serves on the local Blue Zones steering committee, agreed that the Project has been a boon. He called it “one of the most impactful organizations I’ve seen in our community considering the progress it’s made in the past three years.”

From his office at KEIR Manufacturing Inc., he said, he regularly witnesses walking groups in the Project’s trademark blue T-shirts gathering on the nearby Estatoe Trail. They are evidence that the group has fostered connections, he said, and “I’ve seen it with my own eyes.”

Other Council members are more skeptical.

When the new Comprehensive Plan was first presented to Council at a meeting last month, a majority of the members objected to including a Blue Zones’ recommendation that the city build 400 units of affordable and workforce housing in the next 10 years.

Council members and city planners were well aware of such a need, Mayor Pro Tem Gary Daniel said at the meeting, and “I’m a little offended that this Blue Zone paragraph is in there to, in essence, take credit for the work of our staff.”

More generally, he said of Blue Zones afterwards, “I think there is some truth to the statement that a lot of the work they are taking credit for is being done by someone else, whether it’s the city or the Ecusta Trail folks.”

Dinkins was more critical, writing that “increased spending on the Estatoe Trail or downtown was a Council decision, made with support and guidance from city staff . . . Splashy special presentations by BZ to Council do not directly ‘result’ in increased spending, at least not in my opinion.”

The Participants

But true appreciation of the Project’s contributions in Brevard requires looking behind the numbers, Hankey said in an hour long-interview last month. Blue Zones’ real benefits can be seen in testimonials on Youtube, can be heard in the stories of participants “really telling us about how it affected their lives.”

Roya Shahrokh, 62, who recently moved to Brevard after early retirement from a career in finance, attended a purpose workshop in the Blue Zone office on West Main Street last month.

The first hour was devoted to an inspirational presentation quoting authors as diverse as Nelson Mandela and Matthew McConaughey, the second hour to an exercise that resulted in a purpose statement identifying Shahrokh’s gift for “shaping environments,” which she could use “to design things for the benefit of others,” she said.

“The intention is great,” she said, of the workshop, though she noticed that of the three full participants, one was a life coach from Hendersonville and the other a naturopathic doctor from Greenville, S.C..

“The part that seemed odd to me was that I felt like I was the only one there to find a purpose and the other people were there, maybe, to find clients,” she said.

Katina Hansen, 58, co-owner of downtown’s Blue Ridge Bakery, who is featured in a Blue Zone testimonial, spoke in a follow-up interview of dramatic improvements in her personal fitness and her commitment to expanding healthy options available at her Blue Zones-approved business.

Eight years ago, she said, “I weighed 325 pounds and I was miserable,”

After dropping 100 pounds, she was able to start walking and four years ago joined a CrossFit gym. Yes, she made these changes before Blue Zones arrived, but the program encouraged her to keep at it, and to add Blue Zones items such as Crunchy Chickpea Salad and Lentil Salad Wrap to the bakery’s menu.

“It’s so much easier to do good stuff when you are around people who are doing good stuff,” she said.

Margarette Kennerly said the walking group she started at her church, Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, has furthered not just one Blue Zones goal, regular exercise, but also two others — building social connections and a sense of purpose.

She knows she has to show up to lead the group, she said, and told how its members rallied around a fellow walker during a severe and ultimately fatal health crisis.

“We were able to support her and support her husband,” she said. “It’s become a little community beyond walking.”

Students’ Voices

The Brevard Project’s achievements are more impressive, Hankey said, because it was launched at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. And she is perhaps proudest of its response to tragic signs the pandemic was fueling an already apparent youth mental health crisis.

These efforts were not part of Sharecare’s “blueprint,” she said, “but happened because we listened to the needs of the community and organically responded.”

Blue Zones was one of the early backers of TC Strong, a community organization formed during the 2021-22 school year to support the emotional health of young people, said TC Strong Coordinator Rik Emaus. Hankey, he said, “became part of the front-line work group that develops our strategies and helps establish our priorities.”

Along with another organization and TC Strong, Blue Zones helped expand youth outreach last year by forming Voice of the Students chapters at the county’s high and middle schools, Emaus said: “Blue Zones was incredibly supportive and is one of the three legs of the stool of community support for Voice of the Students.”

Besides working to encourage healthier eating in the cafeterias in the county’s five Blue Zones-approved schools, Hankey said, the Project has also made purpose workshops available to all high school seniors.

After leading one of these workshops at Brevard High School, she said, “a girl came up to me, fully masked and her eyes had just welled up with tears and said, ‘Nobody ever listens to us and this is the first time I felt heard’ . . . The impact (of Blue Zones) on just that one child’s life is worth every dollar we have spent in the community.”

Moving Forward

Even when Blue Zones departs, this work will go on, said Hankey and Charlotte Shackleford, the Project’s organization coordinator.

They will use their experience as former teachers and, in Hankey’s case, as a certified nutritional health coach, to form a new nonprofit that aims to advance many of the same goals as Blue Zones.

Called SparkPoint,” it will “ignite well-being” through improved personal and community connections. It will build on the contacts and experience Hankey and Shackleford gained working for Blue Zones, and draw on the knowledge of the many Blue Zones volunteers.

It will be a leaner organization than Blue Zones, funded with local contributions and serving residents throughout the county. It will also be able to respond quickly to needs that present themselves, as Blue Zones did in its work with TC Strong.

“We’re not confined,” Hankey said, “not by Sharecare, not by anybody.”

That sounds like a plan, said Emaus.

“This is an opportunity for it to truly become a local effort,” he said, “one that better fits our community and would be easier for all our community to embrace.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

This was a fabulous article. Marla thank you for your comments! I forwarded this to so many people!!

Dan, thanks for writing the article!!

One of Dan's talents is the objectivity of his research and reporting -- listening well and presenting complexity, like that of Blue Zones Project in Brevard. Seems to me, from this read -- and from living in Brevard -- that BZP has made strides among us, contributing to the wellbeing of many, including those kids touched by TC Strong as well as diners at such places as Blue Ridge Bakery and Sunrise Cafe. And yet, goodness knows, we have a long way yet to go, collectively as diverse communities even here in one small mountain town. Good that a not-for-profit, SparkPoint, is being launched!