Lawmakers "Bring Home the Bacon," but There's a Better Way to Spend Taxpayer Dollars

The $33 million in legislative earmarks for local utility projects are badly needed, officials said, but reports say this funding method "circumvents" the state's competitive grant process.

The $33 million worth of earmarks for local utility projects packed into the current state budget is a sign of the times — an era of big and not-especially-discriminating government spending.

This summer, the US Department of Transportation awarded two grants to the city of Brevard totaling $46 million and essentially paying twice for the same job — building unfunded stretches of the multi-use Ecusta Trail.

Transylvania County received an initial $6.7-million grant from the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and, later that year, a $7-million earmark from the state’s pot of ARPA cash that was once expected to pay for a new water plant. It didn’t.

Some of that first chunk of ARPA money could be set aside to help pay for a new cell at the county landfill, according to budget talks last summer. But $7 million in the current state budget was also set aside for just that purpose, along with another $2.3 million appropriation to Blue Ridge Community College for capital improvements.

Brevard received one of those previously mentioned utility earmarks, $13 million to get started on the replacement of its aging sewer plant. But like the two $10 million appropriations to the county and the town of Rosman, it was approved without a formal application detailing need or benefits.

Rosman Mayor Brian Shelton said he’ll use the town’s earmark to pay for a badly needed drinking water plant, but also said that it could take “months” to work out a spending plan with the state.

The appropriation to the county, which doesn’t run a utility system, was lumped under a general budget heading of “water and wastewater” appropriations, and County Manager Jaime Laughter has since referred to the target of this funding even more generally as “infrastructure.”

All the money is, of course, welcome. And a range of local and state officials say these utility appropriations fall far short of the amount needed to address a dire and a longstanding need. Upgraded utilities are vital, they say, to promote public health, expand economic opportunity and address the county’s affordable housing crisis.

Also, the state’s largesse is hardly limited to governments in Transylvania. The budget includes a record $2 billion worth of handouts for water and wastewater projects secured by state lawmakers.

This kind of spending goes by a variety of names: “earmarks,” “appropriations,” “pre-allocations” or, less kindly, “pork.”

Whatever the term applied, is it the best way to distribute taxpayer money?

Absolutely not, at least when it comes to utility funding, according to the State Water Infrastructure Authority, which was created a decade ago to fairly and efficiently award grants and low-interest loans to local governments based on a competitive application process.

For five straight years, the Authority’s annual report to lawmakers has recommended that they “limit or eliminate pre-allocation of project funding,” which one report said “circumvents” the competitive grant process.

That this trend has only accelerated in the face of these concerns can be blamed on both robust budgets and politics, Brian Balfour, senior vice president of research for the conservative-but-nonpartisan John Locke Foundation wrote in an email:

“In my opinion, that’s the result of two main factors — revenues recovering and growing at a healthy clip since the Great Recession and Republicans enjoying a majority for over a decade, making them more comfortable with ‘bringing home the bacon’ to home districts to maintain support from constituents.”

A Better Way

Maybe nobody better understands the statewide need to upgrade local utility systems than Shadi Eskaf, who serves as both non-voting chair of the Infrastructure Authority and director of the state Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Infrastructure (DWI).

The Authority’s six-year-old Statewide Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Master Plan estimated the costs of needed facilities at between $17- and $26-billion “over a 20 year window,” he said in an interview last week, “but that was back in 2017, so costs have gone up.”

No matter how lawmakers distribute utility money, their commitment to bridging this funding gap is “fantastic,” he added. “We're happy to make sure the funds are out there to help with public health and environmental protection and economic opportunity.”

But needs always exceed the available funding, which is where the Authority comes in.

It approves spending based on DWI recommendations, which are in turn based on Priority Rating Systems that score applications based on factors such as the environmental and economic benefits of planned work, the urgency of the need to replace “failing” facilities, and the ability of the local governments to pay for upgrades without the state’s help.

The process uses “prioritization criteria to build public confidence in its funding decisions,” the Authority’s 2022 report says.

A prime local example of how it works: a series of grants and low-interest loans Brevard has received from the Authority allowed it to bolster its network of wastewater pumps and pipes, greatly reducing spills into the French Broad River.

For several years, almost all of the money allocated for such projects statewide was distributed through this competitive system and at relatively consistent levels.

In the 2013-14 fiscal year, for example, the Authority awarded $226 worth of grants and loans through the various programs it oversees — many of which are backed by federal funding. In the 2016-17 that total came to $304 million.

The amount distributed by earmarks, however, climbed to $6.9 million the following year, which prompted the Authority to include its first recommendation to limit the practice in its 2019 report.

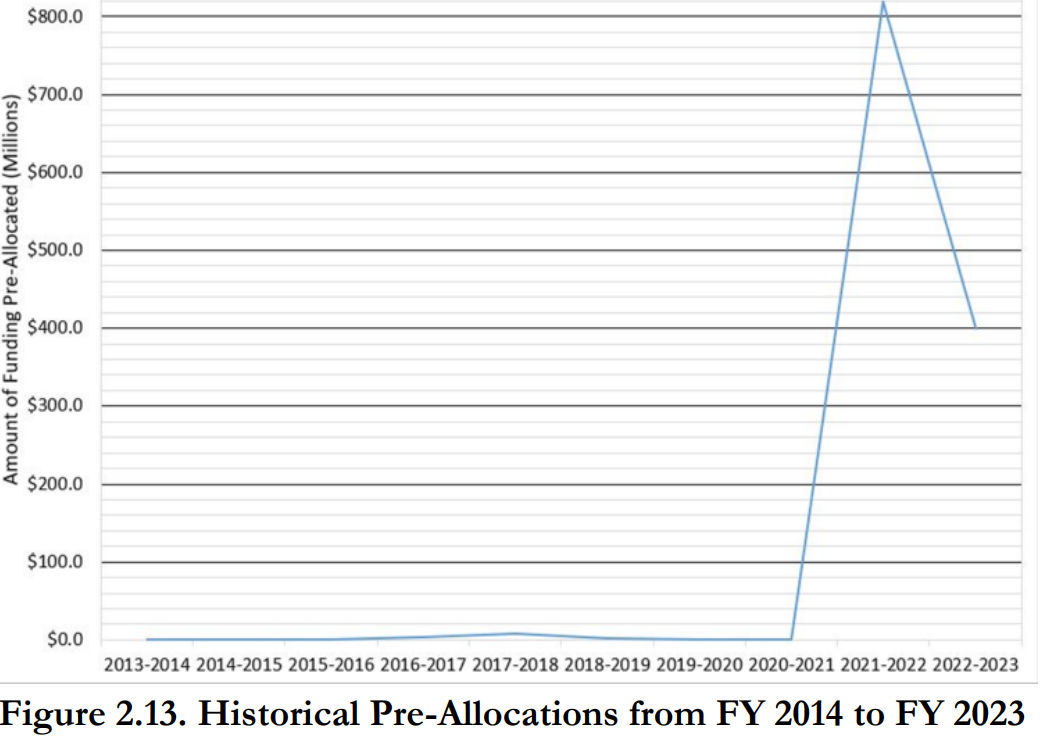

Then came the Covid-19 pandemic and relief programs such as ARPA, which starting in the 2021-22 fiscal year, “increased the amount of preallocated funding by an order of magnitude of a hundred,” the Authority’s 2023 report said.

The biennial budget approved in late 2021 included $821 million in water and sewer project earmarks for the 2021-22 fiscal year and lawmakers were able to secure an additional $386 million the following year, according to a spreadsheet provided by DWI.

As a result, less than half of the funding available for such work during those fiscal years was distributed through the competitive bidding process, the report said:

“The amount of funding . . . that was pre-allocated ($1.2 billion) exceeds the amount which was available for competitive funding ($1.1 billion) by over $126 million.”

And with state revenues soaring, that trend is accelerating.

The Authority awards grants and loans twice a year and though the amount it can spend in its spring funding cycle hasn’t yet been determined, the $235 million available for the applications received in October is dwarfed by the $2 billion worth of budget earmarks.

The consequences of this spending pattern is most clearly stated in the Authority’s 2022 report, which said it drains the pool of money awarded through a “competitive, transparent application and review process,” and “greatly weakens (the Authority’s) efforts to keep the funding process equitable.”

Spending Restrictions

Such recommendations address the method of distributing money. But Eskaf provided assurance that no matter whether funding takes the form of earmarks or competitively awarded grants, it receives the same level of scrutiny from DWI, including requirements covering engineering, design and competitive bidding.

The county’s ARPA money was also subject to guidelines that allowed all the subsequent use of its funds, Laughter said.

One such restriction — the tight spending deadlines attached to ARPA funding — contributed to lawmakers’ decision to funnel the state’s share of these funds through earmarks rather than time-consuming, competitively awarded bids, Laughter wrote in an email.

Concern about not meeting that requirement was also one reason the county diverted its $7 million chunk of state ARPA funds.

In April of 2022, the County Commission approved a plan to spend this money on the planned Rosman water plant. But because the facility would have cost far more than that amount and taken longer to build than ARPA guidelines allow, much of those funds were instead directed to other utility work, Laughter wrote, including the recently completed extension of Rosman utility lines along the US 64 corridor and connecting these pipes to Brevard’s water system.

It’s an example of the county’s cooperation with other local governments, which was one of the points Laughter emphasized in an emailed response to NewsBeat’s questions about state funding. Her other main theme was the county’s vast unmet capital needs.

All the projects that ultimately received funding were included in a January letter to state Rep. Mike Clampitt, R-Bryson City. The letter, after referring to the “capital challenges our county faces,” sought a whopping $376 million in state money, including unfunded asks of $50 million for a new county courthouse and $100 million for “high school improvements.”

The $45-million sum requested for a county “water treatment/water intake plant” was based on a cost estimate included in a 2014 study from the McGill engineering firm that looked at countywide needs.

“While the county is not a utility provider, we have been involved with both the city and the town in understanding and advocating for infrastructure needs,” Laughter wrote.

Filling all those needs is crucial to promoting “economic development and the future of housing affordability” she wrote, and the cost will “well exceed” the $33 million received by the city, town and county.

The terms of the first, $6.7 million ARPA grant allowed small counties to use it for “revenue replacement” according to county documents. This means it can be “be used in capital planning overall,” Laughter wrote, and not just for the landfill expansion, which is both an immediate and ongoing need.

Not only must the county build a new cell in the near future, she wrote, “we will also need to be prepared by 2030 with the next landfill cell . . . if we are going to continue to accept solid waste at the site.”

Brevard and Rosman

But the cooperation between local governments that Laughter touted has also run up against limits, Shelton said.

The town and county were unable to reach a long-term utility agreement covering the funding and operation of the Rosman plant, and the earmark the town received was the result of the town’s separate request and will allow it to start building the plant on its own.

It’s sorely needed, Shelton said, because the town’s current system of wells and tanks — some of them decades old — is inadequate to handle the development expected to follow the new utility lines, much less the long-term growth the town hopes to serve.

Asked last week about an earlier, controversial proposal to sell the town property he owns for the site of the plant, he said he is in the process of selling “most of that land” to another buyer.

“I’m not selling it to the town,” he said.

Though he has not yet received state guidance about the use of the earmark, he intends to devote it strictly to the plant, the cost of which is beyond the reach of municipalities the size of Rosman.

“It’s hard for a small town to have the fund balance to work on these projects,” he said, “so the appropriation is tremendous for us.”

Brevard’s leaders also say it can’t afford a new, $65-million plant without outside sources of funding. That price is a rough estimate based on a 2014 engineering report that highlighted the need to replace the now-36-year-old plant, a need that has grown far more acute since, said City Manager Wilson Hooper.

Its antiquated treatment method already struggles to handle highly contaminated waste from, for example, breweries, and is wholly inadequate to support the industrial expansion the city craves.

Though Hooper, like Shelton, has not received guidance for the use of the money, he said he hopes to spend about $1 million on an engineering study providing, among other information, projections of future demand, options for treatment methods and an up-to-date cost estimate.

This will allow the city to proceed with future phases of the project, he said.

“I’m hoping that (the report) will be sufficient enough that we can submit it to the state for our first round of permissions and permits,” Hooper said.

“Not Arbitrary”

Local officials praised Clampitt lavishly for his work in securing funds for their projects. And it was only after extensive communications with them, including a full day of meetings and tours of local water and sewer facilities, that he pursued the earmarks, he said.

“It’s not arbitrary spending,” he said.

Clampitt wasn’t in on the high-level legislative discussions that assigned the total amount in the budget available for utility earmarks, he said, but agrees with this priority because of the crucial role that water and wastewater access plays in building the economy and supporting affordable housing.

Because of such benefits, he “disdains” words like “pork” and “bacon,” he said. “I don’t like that particular connotation for bettering the life of communities.”

He also echoed the arguments from Hooper and Shelton about financial need, saying his job is to help the small communities that he represents. The effort is necessary, he said, to level the playing field between rural Western North Carolina and wealthy urban areas such as the city of Charlotte.

Why, he asked rhetorically, “are they needing state dollars to fund their projects when they have a tremendous tax base?”

The “Affordability Criteria”

But funding equity is also a primary goal of the DWI’s Priority Rating System.

A close look at the system shows it is receptive to all the arguments local officials made to justify the earmarks they received. If a city, town or county can show a need to expand a utility facility and/or replace an aging one, for example, it gets points through the Rating System.

The same is true for demonstrations of financial need.

The competitive bid process includes “affordability criteria,” the Authority’s 2022 report said, and one danger of instead distributing funds through earmarks is that state will end up helping “recipients that could afford some amount of debt . . . and need less grant funds.”

“There are a lot of things that go into that Priority Rating System,” Eskaf said. “One example would be prioritizing funding to communities that need financial assistance the most.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

This is watchdog journalism at its best. Maybe earmarks do serve a purpose, maybe they don't. Maybe an objective needs-based approach is best. Maybe each funding method has its pluses and minuses. But without access to the facts, taxpayers don't know they even need to answer these questions, let alone come to a conclusion about what's the right balance for NC taxpayers. If earmarks are back in fashion. The NCGA could do worse than throw a few public interest bucks to local news sources like NewsBeat.

Dan, since the money is being distributed through earmarks, as championed by members of the NCGA, do we know if counties represented by Republicans received more money than those represented by Democrats? I understand the urban/rural divide when it comes to access to capital, but still..... Were Democratic members of NCGA able to obtain funding through the earmarks?