Why Is the County's "Best" Teacher Taking Early Retirement? It's about Respect

Cuts in benefits, lagging pay and the "Parents' Bill of Rights." All have diminished trust in her profession, said Jeanne DeJong, who represents a trend in early teacher departures.

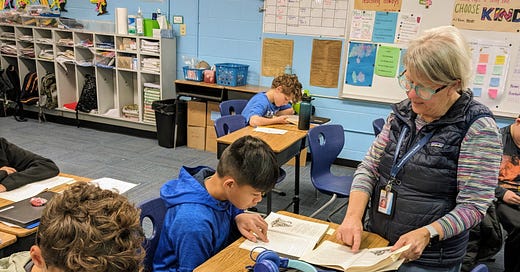

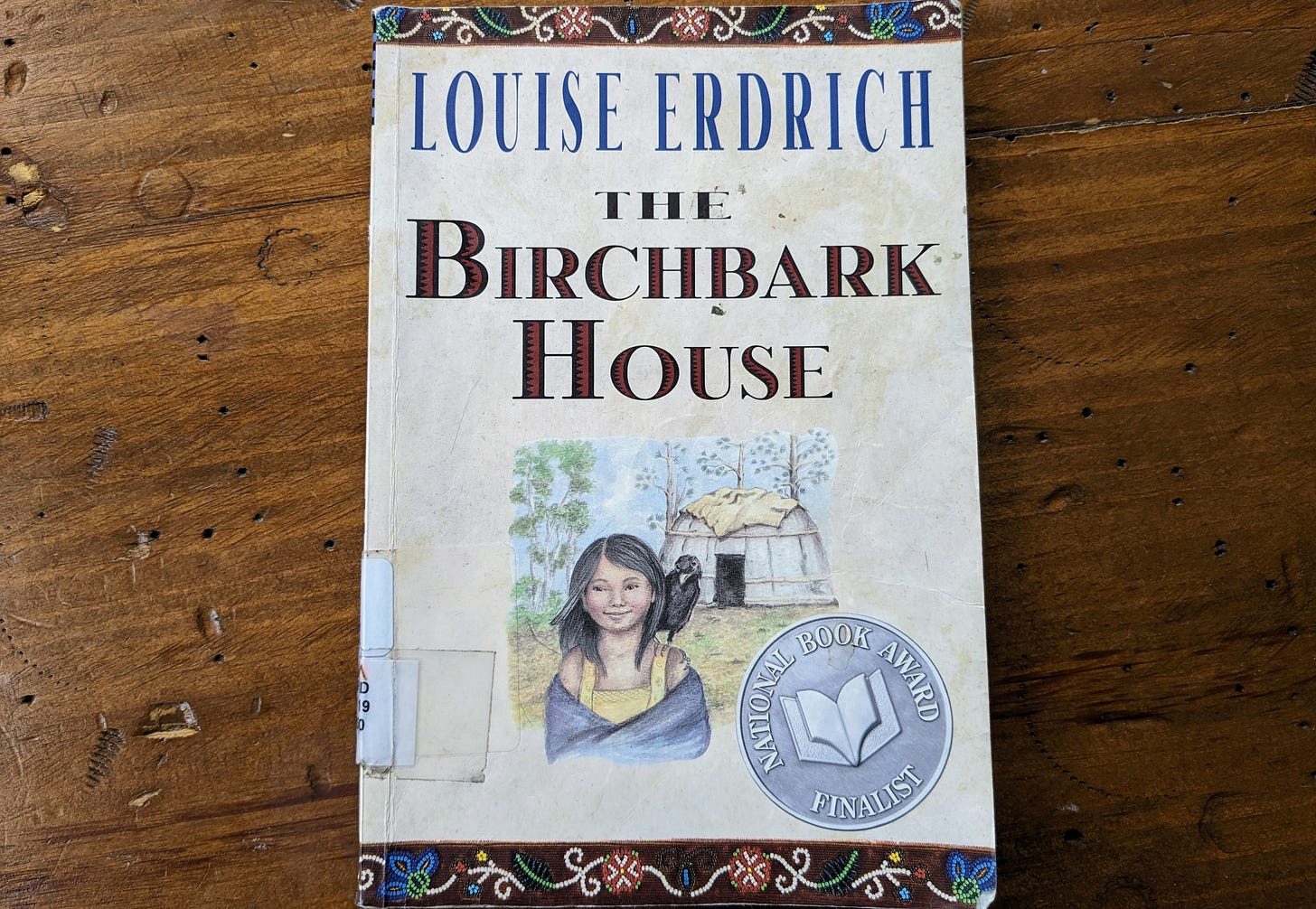

BREVARD — Hands shot up in Jeanne DeJong’s fifth-grade class — not to offer answers to her question about the previous week’s Latin root word, but to demonstrate it.

“Got it!” she said. The word was “man,” meaning ‘hand.”

“What was it two weeks ago? Show me,” DeJong continued as the aisles between desks filled with extended legs and wiggling sneakers.

“Yeah!” she said. “ ‘Peds.’ You are showing me your feet.”

The current week’s root, “ject,” or “throw,” called for another demonstration.

“Show me with your face what ‘dejected’ means,” she said, prompting despondent-looking heads to collapse on desk tops.

“Oh, nice,” she said. “I see it. ‘Dejected.’ To feel sad, to feel thrown down in spirit.”

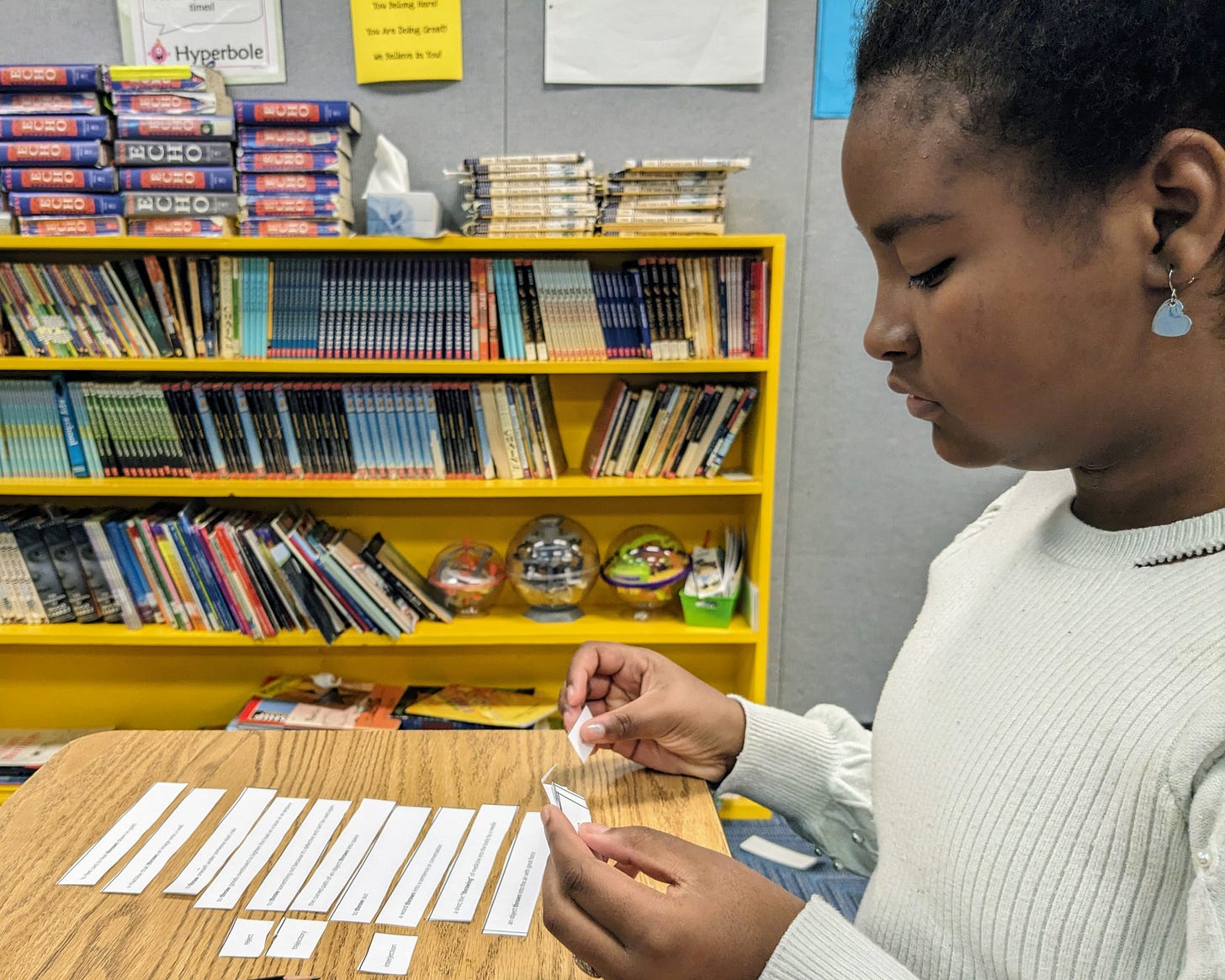

Engagement. It has long been a hallmark of DeJong’s English Language Arts classes at Brevard Elementary School. So has the depth and variety of instruction packed into her 90-minute sessions, which on this day last month continued with readings from an acclaimed novel, The Birchbark House, set among American Indians living near Lake Superior in the 19th Century.

Topics ranged from comprehension strategies to the complex relationships between the story’s characters. There was history — about the culture of Native Americans and the devastating impact of smallpox on their tribes. There was science — the immunity afforded by previous exposure to viral infections.

Beyond covering the required curriculum, said Brevard Elementary Principal Michael Kirst, “it’s up to the teacher to add more ingredients, more flavor to the lesson, to make it more fun. And (DeJong) does it to the max every day.”

Or did do it. This class was one of DeJong’s last.

Widely praised as one of Transylvania County Schools’ best educators, DeJong, 61, is part of a trend steadily sapping expertise from the district: veteran teachers leaving the profession short of the 30 years needed to collect full state retirement benefits.

She retired Jan. 31 after 23 years as a teacher in North Carolina — and, she said, after watching the erosion of classroom autonomy and the steady diminishment of her profession.

For more than a decade, state lawmakers have stripped benefits and allowed teacher pay in North Carolina to slip far behind that of neighboring states. Last year, they passed a “Parents’ Bill of Rights” that led DeJong to cull her shelves of potentially controversial books, she said, and “just makes me as a teacher feel as if I have to walk on eggshells.”

Some of these same factors are discouraging young people from entering the profession, said Betsy Burrows, a former high school English teacher and current director of teacher education at Brevard College.

Add last year’s broad expansion of a voucher program that diverts state education funds to private schools, Burrows said, and it feels as if public schools are under assault.

“We're going to lose public education. That sounds dire, but I’ve never felt that way before,” she said. “I’ve been teaching since 1984 and I’ve never been this concerned.”

Recruitment and Retention

Transylvania has not yet seen the acute teacher shortages documented in some other districts as more veterans across the state flee the profession and fewer young people enter it.

Numbers of college students enrolled in traditional education programs in North Carolina dropped by more than one third between 2013 and 2022, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality.

Though the headline-grabbing total of nearly 4,500 teacher vacancies reported by North Carolina at the start of the 2022-23 school year dipped to 3,584 last fall, that gap was largely filled by the recruitment of teachers from other professions, who often start with less preparation than graduates of education programs.

Transylvania is currently advertising five open teaching positions, and two other vacancies have been filled by staffers taking on additional classes, said Assistant Superintendent Brian Weaver.

But the total number of openings for teachers and other “certified employees” actually dropped from 39 to 28 during 2022-23 compared to the previous school year, Weaver wrote in an email recently.

The “mobility rate” of teachers leaving Transylvania for other districts in the state was among the lowest in the state during the 2021-22, according to the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s most recent State of the Teaching Profession report. And the attrition rate among the district’s 268 teachers, 7.8 percent, was well below the statewide rate, which had climbed to 11.1 percent that year from 7.5 percent three years earlier.

Still, teacher recruitment and retention is a growing challenge, Weaver told the Transylvania County Board of Education last March before it approved a cash incentive for current staffers who help recruit new employees.

The traditional spring-summer hiring season now lasts all year, he told the Board, and attendance at regional education job fairs, a vital source of prospective teachers, “is running 40 percent of what it was six years ago, seven years ago.”

The district’s ability to attract teachers is aided by Transylvania County’s high quality of life but hampered by a lack of childcare and affordable housing, he said. He also confirmed a trend toward earlier departures evident in lists of retirees recognized by the School Board at the end of each school.

Of the 12 retiring teachers listed at the end of the 2020-21 school year, half had taught 30 years; one had logged 50 years in the classroom and all but one of the departing teachers at least 25. Two years later, only four of the 10 retiring teachers had put in at least 30 years and two of them 20 years or less.

“I don’t believe we’re going to have many candidates in the teaching profession, in the current state it is, who are going to remain for 30-plus years,” Weaver told the Board.

Josh Tinsley, an English teacher at Brevard High School, has seen the trend in his own small department. Two veteran teachers have departed in the past two years, he said, and he and his wife, fellow English teacher Meredith Licht, both plan to retire early.

Their reasons include the proliferation of non-teaching duties, stagnating pay and inaccurate accusations that they are pushing destructive views about race and sexuality.

“The political environment feels hostile and the ongoing social environment feels hostile,” he said. “I mean, we are being full-on attacked.”

The “Best” Teacher

Longtime teachers aren’t always the best teachers, Weaver and others said. But it’s also clear that the mastery DeJong is known for can only be built with experience — and that she is the kind of teacher the district doesn’t want to lose.

“I can honestly say, she’s the top, she’s the absolute number one,” said a longtime fellow teacher at Brevard Elementary, Lisa Pauer, whose own now-adult children still rave about their time in DeJong’s classes. “She’s on a whole other level.”

DeJong (pronounced de-young) arrived at school at 6 am daily to ensure her lessons were in order, Pauer said. The district’s director of K-8 curriculum, former Brevard Elementary Principal Carrie Norris, recalled DeJong dressing up in costume to teach Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and dropping eggs from the roof of the school to illustrate the power of gravity.

DeJong was an early advocate of outdoor learning to allow safe face-to-face instruction during the Covid-19 pandemic, Norris wrote in an email, and she made a practice of sending hand-written cards to her former students when they graduated from high school.

“An absolute gem,” Norris called her. “Mrs. DeJong will do absolutely whatever it takes to make learning meaningful and encouraging for students.”

DeJong’s devotion was reciprocated with a stack of congratulatory retirement cards and letters.

One former student, now a 26-year-old doctoral candidate, remembered the warmth DeJong extended to her as a young girl after her mother had been diagnosed with cancer and credited DeJong with imparting “a love of learning for me that has guided me ever since.”

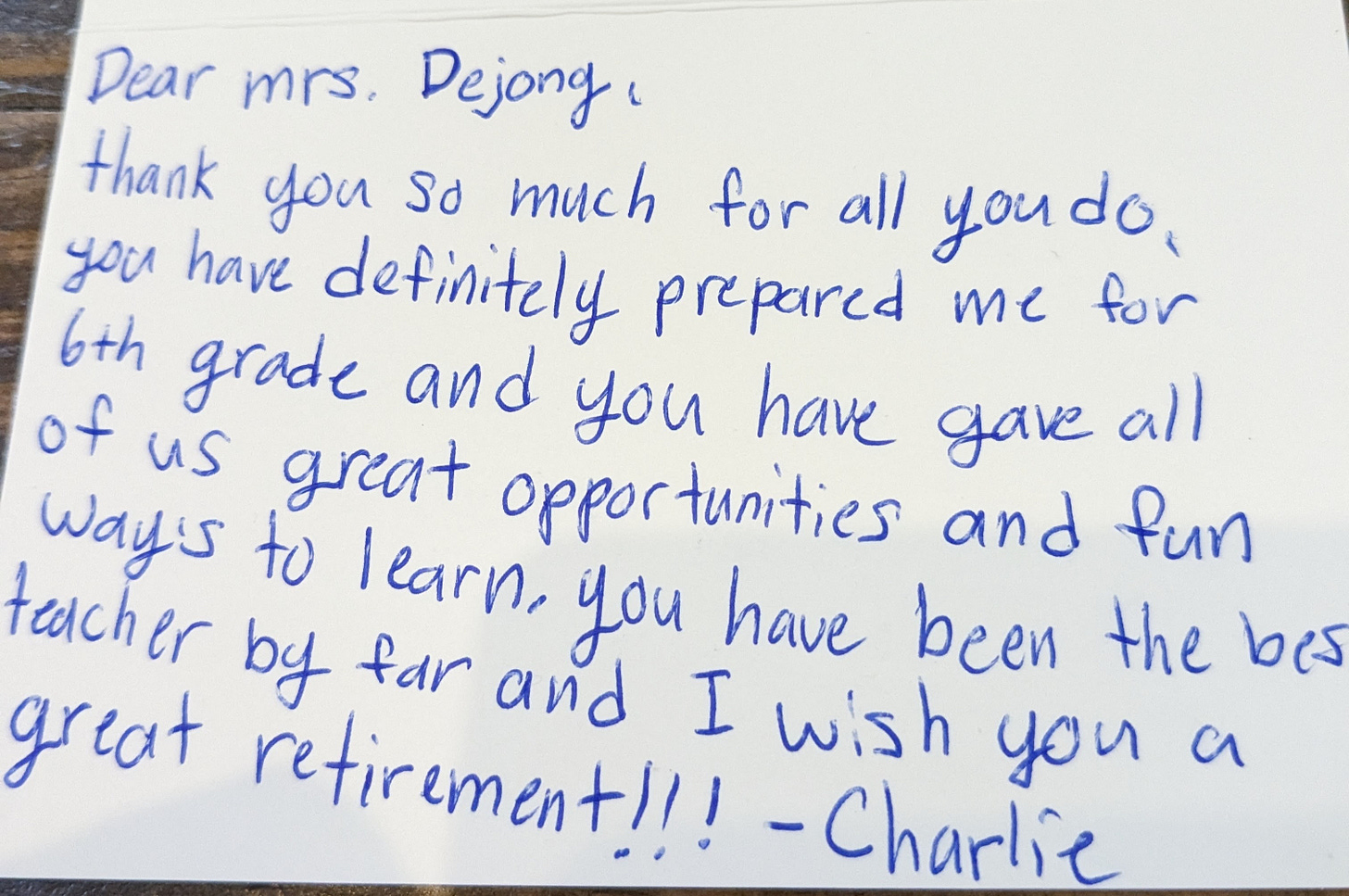

“You have been the best teacher by far,” a current student named Charlie wrote in a card that also thanked DeJong for providing “great opportunities and fun ways to learn.”

The Power of Novels

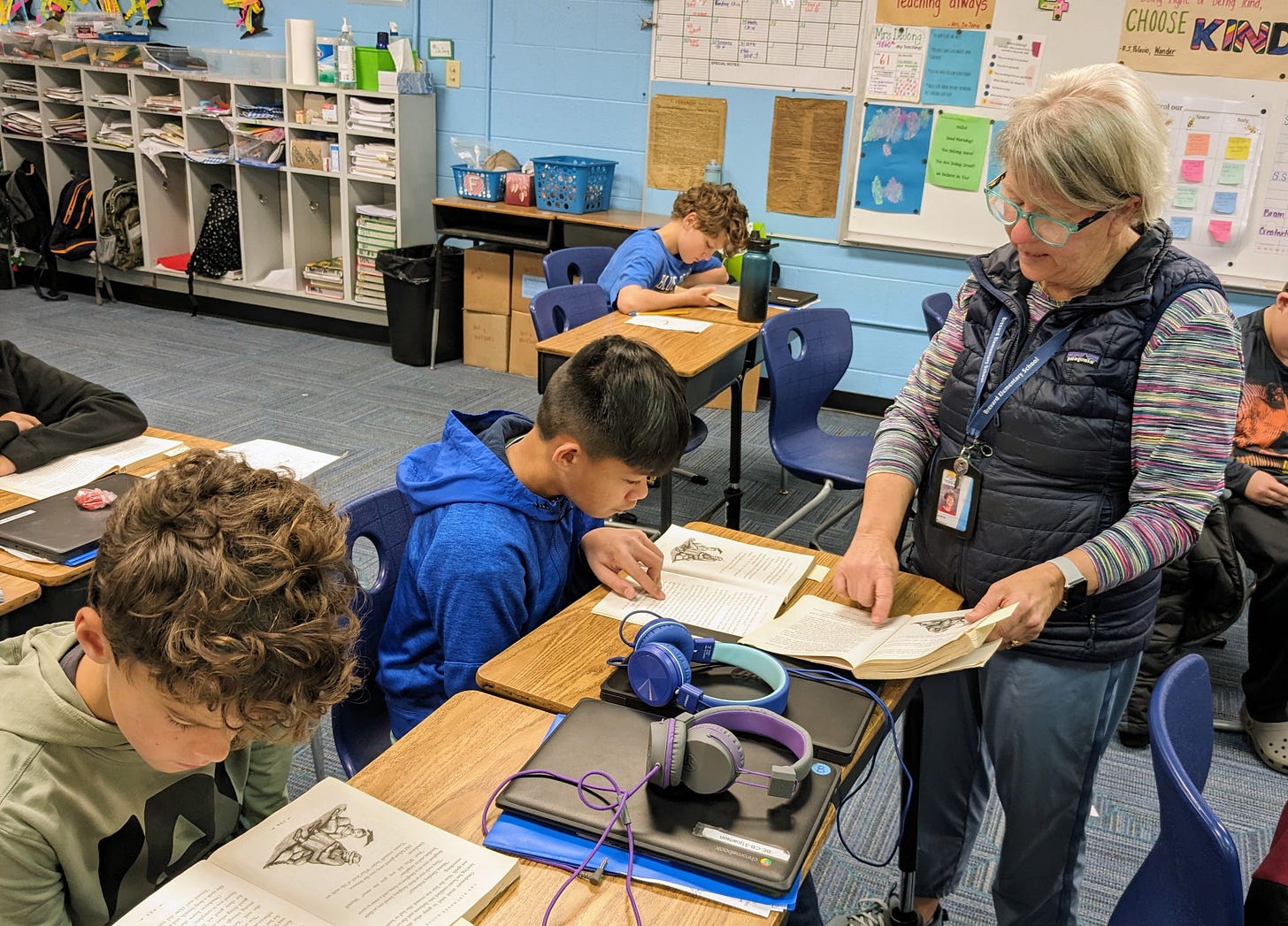

The reading comprehension exercise that started DeJong’s class last month didn’t seem especially fun. But, DeJong said afterwards, it allowed her to hammer home techniques — highlighting key passages, for example, and rereading the text — that build students’ confidence and “bring them into everyday, happy learning.”

During the subsequent vocabulary lesson, students didn’t just study the 10 words and definitions based on the Latin root. They cut them out and sorted the resulting jumble to match words with meanings, enlisting senses other than vision and employing extended concentration that cements lessons in students’ minds.

This is also accomplished by teaching novels such as Birchbark that feature powerful narratives and highly relatable main characters, in this case an eight-year-old girl named Omakayas.

As DeJong and students took turns reading from the book, she prompted them to recall its main themes. They remembered that passing seasons illustrate the cycles of life, death and rebirth. They identified the significance of a rare sweet treat for tribal members that the students had previously made in class — and that became a source of Omakayas’ bond with her baby brother.

“Just because it’s fun — maple sugar!” DeJong said.

Students also knew that Omakayas initially resented the gift of hide scraper that consigned her to a difficult and dirty job but that it evolved into a symbol of pride as she realized how this work allowed her to contribute to the well-being of the tribe.

Which turned out to be her destiny. A dying stranger brought the “itching disease,” smallpox, to her village, sickening Omakayas’ family members and killing her little brother.

How did she remain well enough to care for them?

It was the book’s central mystery and it was solved by a student named Cullen using a strategy covered at the start of the class.

Omakayas was not born into her family but adopted as the only survivor from the island home of a tribe that had been wiped out by smallpox, a scene that opened the book.

DeJong asked Cullen how he had figured this out.

“By looking back in the text, back in the very beginning,” he said, flipping through his copy of the novel. “It says ‘The Girl from Spirit Island.’ ”

“Good!” DeJong said, before reading the words of a usually gruff tribal elder who told Omakayas the story of her adoption in the book’s last chapter.

“ ‘This was before you were two winters old,’ ” DeJong read to the rapt class. “ ‘You were the toughest one, the littlest one, and you survived them all.’ ”

Why Retire?

DeJong’s mother was a teacher, her father a professor at the small Ohio college where she earned an undergraduate degree in computer science.

After an unhappy stint in that field, she said in an interview soon after her retirement, she remembered how much she enjoyed working as a swimming teacher as a teenager and tutoring during college.

“I guess I figured out that’s what I really like to do,” she said of teaching.

She returned to earn a master’s degree at Emory University in Atlanta and then taught in Georgia for seven years (time that does not count in the calculations of her North Carolina retirement benefits).

She remains grateful that she found a profession that suited her so well. She never lost the thrill of guiding students such as Cullen to reach thoughtful insights.

“Teaching is wonderful. I mean I wouldn’t do anything else,” she said. “I'm happy every day in terms of actually seeing the kids’ faces, seeing they enjoy it and are making connections.”

So why leave? Why forfeit an estimated half of her pension income by retiring early?

There are personal reasons. Her husband runs a successful business. Her daughters are grown and financially independent. She wants to help raise her two young grandchildren.

And some of her dissatisfaction stems from requirements adopted with far less controversy than, say, the Bill of Rights.

Following state guidelines, a district employee now uses testing data — and, DeJong said, inadequate input from teachers — to decide which students are pulled from class to receive reading “intervention.”

“It’s very upsetting to teachers when that happens,” DeJong said. “We are professionals. We know what those students can and can’t do.”

A new reading series that emphasizes nonfiction has crowded out time available for the novels that she has found best create a love of reading.

This year she was able to compromise, incorporating some of the series while continuing to teach books such as Birchbark. But she couldn’t have done that indefinitely, she said.

“I know pretty much for a fact that if I wasn’t retiring it would have been an issue.”

“Bill of Rights”

She could also see trouble brewing from the Bill of Rights, passed by the North Carolina General Assembly last year to increase parental control over education.

Both lawmakers representing Transylvania, Rep. Mike Clampitt-R, Bryson City, and Sen. Kevin Corbin-R, Macon County, were co-sponsors.

Corbin didn’t respond to a request for comment, but Clampitt said the Bill was justified because “parents know what is best for their kids.”

The need for provisions that enhanced the right to challenge teaching material, he added, has been proven in another county in his district, where activists objected to a book housed in the children’s section of a regional library. It was so “risque,” Clampitt said, that it couldn’t be shown by news media covering the controversy.

“But it’s okay for a fifth grader? Give me a break,” he said.

DeJong, repeating a common observation, said most of the policy changes adopted by the Board last fall to comply with the law merely reinforced powers that already existed.

Their main direct impact, she said, has been diminished participation in routine vision screening offered at schools. Parents were previously allowed to opt out but must now opt in, meaning a misplaced form could mean a lost opportunity to ensure that children’s education isn’t hampered by poor eyesight.

More worrisome was the local and national discussion around the Bill. A speaker at one Board meeting last fall, for example, denounced “people right in our community intent on sexualizing our children.”

Never happens at the schools, DeJong and other teachers said. Neither does the teaching of Critical Race Theory, which opponents say fosters division between black and white students by emphasizing embedded racism.

It’s a pattern addressed in the proposed HB187 that Clampitt supports and that would “ban anti-American school indoctrination” according to a document he shared with NewBeat.

Such efforts, DeJong said, have made her leery of offering any books that might be seen as putting the country in a bad light.

Last year, after receiving approval from a parent, she sent a child home with a book that explores American racism through the eyes of historical figures.

It’s one of several volumes she later pulled from her classroom.

“I don’t even have it on my shelf this year,” she said.

The Bill of Rights also made her “think twice” about books covering established historical facts that now seem potentially controversial — the segregation of Hispanic residents in California, the internment of Japanese citizens during World War II, even the spread of smallpox to American Indians from white populations, a central theme of Birchbark.

She didn’t avoid discussing these books this year, she said, but she might have if she planned to stay in teaching.

“Those are things that just make me nervous now.”

“A Real Profession”

Also, she and other educators said, the Bill of Rights shouldn’t be seen on its own but as part of a decade-plus pattern of legislative action that has hampered recruitment and retention.

In 2013, state lawmakers removed protections against peremptory teacher firings and eliminated the 10-percent supplement for new educators receiving master’s degrees.

In 2014, it cut “longevity pay” meaning that after 15 years on the job teachers can look forward to only one more seniority-based salary bump — at 25 years.

A program that provided a bridge in health-care coverage for retired teachers until they qualify for Medicare was removed for teachers hired after the start of 2021.

Meanwhile, the average teacher salary in North Carolina — ranked 19th in the nation in 2002 — had dropped to 33rd by 2022, according to a report last year from BEST NC, a business-backed education nonprofit. Pay for starting teachers, meanwhile, fell to 46th in the country, according to a report last year from the National Education Association teachers’ union.

Clampitt touted teacher raises averaging 7.8 percent that were included in the biennial budget approved last year. That these increases are targeted at boosting salaries of early-career teachers is clearly justified, said Brevard High English teacher Morrey Davis.

“Beginning-teacher salaries in North Carolina were horrifying and they are still not much above that,” he said.

But the resulting 3.6 percent raises for teachers with more than 15 years of experience over the next two years will likely not even keep up with inflation, said Davis, who started teaching at the school two years ago but is considered a 17-year veteran because of his previous career as a college history professor.

And along with the loss of longevity pay, these paltry raises for seasoned educators seem almost designed to discourage long-term commitment to the profession.

“There’s no incentive to stay,” said Davis, who has taken on “sidebar” employment teaching online college classes to help make ends meet.

“I teach here because I want to contribute to the community,” he said, “but they are making it very difficult for people like me to do that.”

Pay and benefits weren’t the main reasons DeJong decided to leave teaching, she said.

The county’s 8.5 percent local teacher supplement is higher than that of most other Western North Carolina counties. Her veteran status preserved her post-teaching medical coverage and protected her from the loss of the master’s degree bonus. Her final annual salary came to nearly $70,000, she said, an amount she considers fair.

Still, she is dismayed by the impact of legislative action on teacher recruitment and the “disrespect” it has shown to her and her peers.

Like Davis, like most other teachers, she said, she was drawn to the field by a sense of mission.

“I want to be one of the people who make wonderful citizens of our society, people who are going to be contributors, people who are going to be kind,” she said.

Doing this well requires a level of skill on par with what is needed in law or medicine, she said. Failing to appreciate this diminishes the value of the expertise she has built over the years, the work she has poured into her classes.

“People think it’s a pretend profession,” she said. “It’s not. It’s a real profession.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Editor’s Note: Another shocking story from The Asheville Watchdog about inadequate care at Mission Hospital, where lapses led to at least three patient deaths according to a “scathing” government report.

Dan, your article made me want to be in Jeanne’s class. She is an artist, combining fun, skill training, history, science, experimentation, freedom to make discoveries, multiple ways to take in and master learning and deep knowledge of her students. This article about her is both INSPIRATIONAL and TRAGIC. I hope she finds ways in a well deserved retirement to find a way to advocate for her education & teaching vision. If not, she has planted 100’s and 100’s of fertile seeds. Thank you Jeanne DeJong! P.S. On my way to checking out Birchbark House.

Another excellent, insightful feature, Dan. My wife and I were so happy that our daughter had Jeanne DeJong as one of her teachers. It's shameful what the current educational system is doing to high-quality, well-intended teachers like Jeanne. Our teachers and students deserve much better!