Time to utter the "Z-word?" That's the question as neighbors say a planned air curtain incinerator is good technology in the wrong place

Owners of the planned incinerator tout its environmental advantages, but a zoning expert says such controversies over location help push the "inevitable" expansion of zoning laws.

Dan DeWitt

Brevard NewsBeat

PISGAH FOREST — Jennifer Poe, who lives on Brown Road next to the planned site of Wood Recyclers Inc.’s air curtain incinerator, said the company’s owners have explained that it produces far less emissions than open burning.

They have promised it will process only untreated wood waste, she said, and is much cleaner and quieter than an industrial grinder.

But when she looks at the grassy, 9.3-acre incinerator site she imagines trucks rolling in and out of its sole entrance on Brown. She pictures stockpiles of stumps and limbs and a possible landscaping retail operation just on the other side of the fence that separates the two properties.

“What they want to do is valid. They want to use their land,” said Poe, 43, who with her husband, Stephen, bought their home on three acres in 2015. “It’s just not the right business for this area.”

Plenty of other neighbors feel the same way, joining a Facebook page Poe launched to oppose the project and/or signing a petition that another neighbor, Don Dubreuil, sent to the state Department of Environmental Quality, which is reviewing Wood Recyclers’ application for a clean air permit.

The incinerator site, about a mile east of the main entrance to Pisgah National Forest, is flanked by homes on large, wooded or pastoral lots. To the north, across Brown, is the Benton Hills subdivision and, to the southwest, on the other side of Hendersonville Highway, is the Brevard Academy charter school.

“Air curtain incinerators are a great idea,” Dubreuil wrote in the petition’s cover letter, “but they should be located in an industrial area, not in the middle of a densely populated residential area.”

The argument echoes that of residents fighting other recent projects — including several Dollar General stores — viewed as dragging down quality of life and property values.

Also familiar is the main obstacle the Brown Road group faces: with a lack of countywide zoning and the narrowly drawn boundaries of the Pisgah Forest zoning district that exclude the incinerator site, the county will likely have no role in deciding whether the incinerator is a good fit for the neighborhood, said County Manager Jaime Laughter. And because the unit will be towed in rather than constructed, it probably won’t need a building permit, said Mike Owen, Transylvania’s code enforcement administrator.

“Unfortunately, at this point, there is no recourse” for preservation-minded residents, “because our County Commission continues to fail to recognize this is a problem,” said Elizabeth Thompson, who fought the construction of the Dollar General store that opened last year on US 276 and Becky Mountain Road.

But it is precisely this sort of project that brings that recognition home over time, said David Owens, a professor of public law and government at the University of North Carolina’s School of Government.

As population and development pressure mounts in counties, so do clashes between the rights of property owners, and so do the demands from residents across the political spectrum to regulate land use.

“It’s a slow process but it has been a largely inexorable expansion of the government,” Owen said. Counties “emerge almost as referees as different property owners have different interests and (these interests) start to conflict.”

“Clean” Wood and Technology

One of Wood Recyclers’ owners, Mary Bearden, said she doesn’t understand why there would be conflict over the incinerator. It’s that much cleaner than the common alternatives for disposing of wood waste, open burning and grinding, she said.

Bearden and her business partner, Katrina Wright, are local residents and “stay-at-home moms,” she said. “This is how we plan to come into the workforce. We wanted to improve the place where we live.”

Open burning pours contaminants directly into the air and results in a zero recycling rate, she said. Industrial-scale grinders, using loud diesel engines that can consume more than 300 gallons of fuel per day, produce noxious dust and potentially pest-contaminated mulch that is often stockpiled because owners can’t give it away.

The air curtain incinerator, made by Florida-based Air Burners Inc., consists of a 30-foot long fire box that resembles a large construction Dumpster. On one end is a 75-horsepower diesel engine that powers a fan blowing a sheet of air over the flames; it consumes about 30 gallons of fuel daily and is quiet enough that it should be barely audible from Brown Road, Bearden said.

The “particulate matter,” which makes up the visible components of smoke, “hit the air curtain and they bounce back,” said Air Burner Vice President Norbert Fuhrmann, who provided a video of the machine in action.

The particles are then reburned in the fire box, so neighbors will see a puff of smoke when a newly deposited load of wood “breaks the air curtain,” he said, but then, “immediately, it is clear again.”

Worries about invisible-but-dangerous chemicals should be allayed by the clean feedstock, “which means not chemically treated in any way and not painted,” Fuhrmann said. “Clean wood waste would be forest slash, agricultural waste and tree clippings.”

If operators rake out the residue before it turns to ash — which Bearden said they intend to do — the incinerators produce biochar, which helps soil retain water and nutrients, as well as sequestering a portion of the wood’s original carbon content.

Both he and Bearden oppose DEQ’s designation of the burner as an incinerator because it does not use an outside ignition source to fire the waste. The technology is well-established enough that a DEQ spokesperson said the agency has previously issued 18 permits for air curtain incinerators, and Fuhrmann said units similar to Wood Recyclers’ — which cost about $180,000, including installation — are used by several federal agencies, including the US Forest Service and the Federal Emergency Management Agency

The owners are so sold on the technology, Bearden said, that the nearest neighbors to the incinerator will be the Wrights, who plan to move into a house on an adjacent property.

“If it’s not something they would want to be a part of,” she said, “it’s not something they would want to live next to.”

Neighborhood Impacts

Poe and Dubreuil said that doesn’t address all their concerns.

While the permit application requests the right to burn six days a week, neighbors have been told the incinerator will burn only a few days per month.

“I took that with a big fat grain of salt,” Dubreuil said. “If it becomes profitable, I’m sure (the owners) will use it as much as possible.”

Bearden said she and Wright plan to start with only occasional use, but acknowledged they might extend hours if the business volume increases. Burning, she added, is the only way to address another concern, the accumulation of large piles of wood waste.

Poe also asked about the extent of the retail operation. Would there be bins of mulch and biochar just on the other side of her fenceline?

Maybe, Bearden said. She said that they hope to serve residents dropping off wood waste, who are likely to be in the midst of beautification projects and therefore natural customers for landscaping products. Such an operation would also mesh with JK Enterprises of WNC Inc., the landscaping and grading company owned by Wright’s husband, Josh, who is also listed as an owner of Wood Recyclers on the DEQ application.

Wood Recyclers won’t sell mulch ground on site because they don’t plan to operate a grinder, Bearden said, but the company hasn’t decided on the details of the retail operation or the marketing of its biochar.

“That’s still kind of in the planning stage,” she said.

Regardless of the form the operation takes, Dubreuil said, the result will be an industrial and commercial enterprise in a residential neighborhood.

“Please try to imagine,” he wrote in his letter to DEQ, “how you would feel if a commercial incinerator was suddenly placed right next door to your house?”

Local Zoning Advances in NC

That’s the sort of question that changes laws, Owens said.

In rural counties, parcels are usually large enough that few uses impact neighbors, and property rights are a simple matter of guaranteeing that residents can use their land as they see fit.

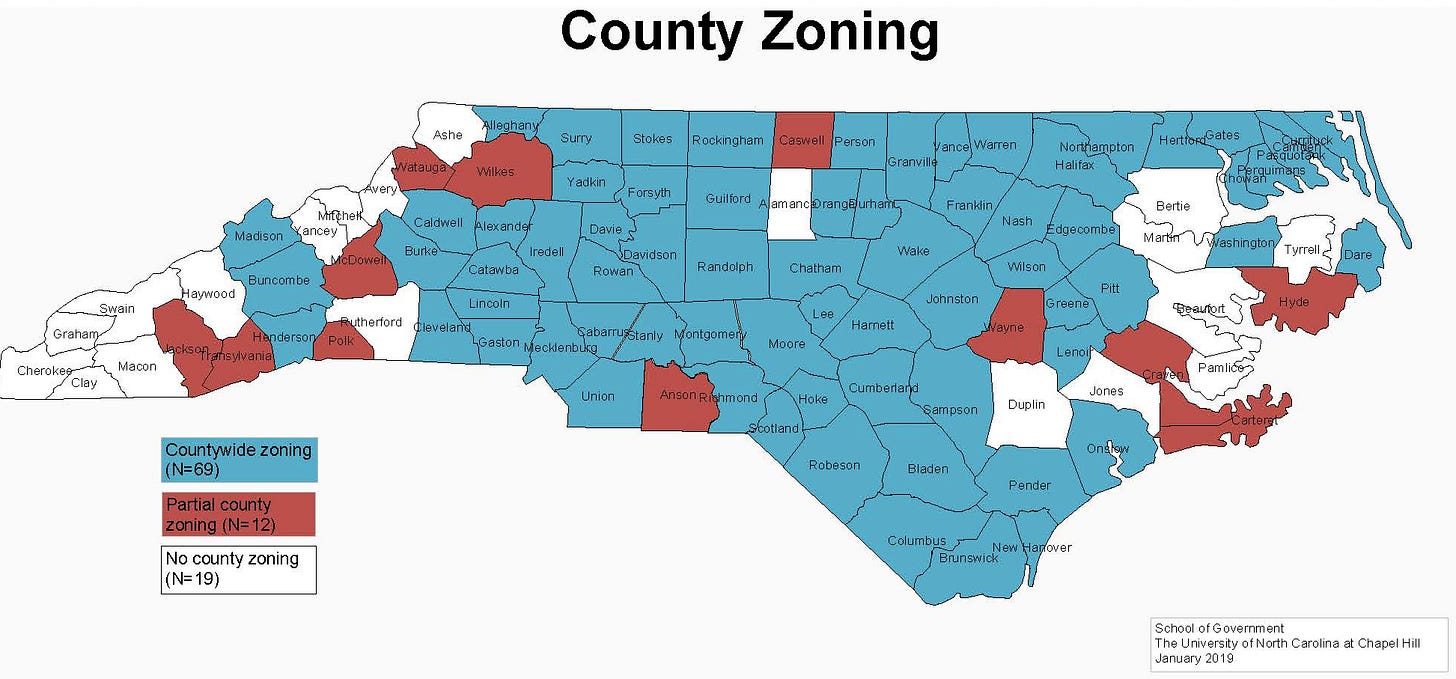

The issue becomes more complicated as communities become more crowded. North Carolina’s cities (including Brevard) typically adopted zoning ordinances decades ago. The state granted counties the right to pass broad land-use regulations in 1959, and so far 69 of the 100 counties in North Carolina have done so. (See map above.)

The lack of such laws in much of western part of the state is not a matter, as is sometimes claimed, of the independent culture of the mountains, but of the region’s comparatively sparse population.

Owens called zoning a “flexible tool,” and counties sometimes start by restricting the placement of unpopular uses such as race tracks, asphalt plants and rock quarries.

Though the development pressures and policy responses vary, he said, the need to address competing rights of property owners in growing counties “inevitably” and “invariably” becomes clear to a wide range of leaders and residents.

“I may be a libertarian who has a great distrust of government and the z-word,” he said, using the name applied to zoning in areas where it is considered beyond the limits of public discussion.

“But if there’s an industrial plant coming in that may harm my family and my property, I’m going to look for some degree of government regulation.”

Is Transylvania Ready for Zoning?

Transylvania is not there yet, said County Commission Vice Chair Jake Dalton.

“I guess I subscribe to the old notion that neighbors should be good to one another,” he said. Zoning may be standard elsewhere, “but up here it’s still a foreign concept.”

He and Commissioner Larry Chapman said that because the placement of the incinerator has not come before the board, they do not know enough about the project to comment in detail. Commissioner David Guice did not respond to requests for an interview on the subject.

But Chapman pointed out that development is restricted in “probably 70 percent” of the county’s land by public ownership, the city of Brevard’s zoning laws, or by the rules on building in subdivisions and flood zones.

“My personal position is I support personal property rights but I also recognize my property rights stop at the property line,” he said.

He said the Commissioners will comment further on the “very contentious issue” of zoning when they address the proposed Cedar Mountain Small Area Plan, which recommends extending the zoning law that covers parts of Pisgah Forest into some areas of that rural community.

Dubreuil said he doesn’t want to wade into the zoning controversy, but sent his petition to the DEQ’s Division of Air Quality in hopes that it will consider the proximity of the school and neighbors in its response to the application, which was submitted on April 12.

“I could send the (county) petitions until I’m blue in the face and it would have no impact,” he said.

The division has 90 days to decide whether to issue the clean air permit, though the clock has not started ticking because it has requested additional information from Wood Recyclers, said Zaynab Nasif, a division spokesperson.

The agency considers whether emissions from a project meet state and federal air quality standards, she said, but also accepts public comment and can require a public hearing if it determines the need.

Poe said there should also be public discussion on the county level. And her growing awareness mirrors the statewide change that Owens mentioned.

Poe said she wasn’t aware of the lack of countywide zoning until she read about the controversy over the Becky Mountain Dollar General. She didn’t see the potential impact on residents until she could picture it from her front yard.

Now, she wrote in an email, “I feel strongly that zoning needs to be in place to protect residential areas, historic sites, the environment and the general integrity of our rural community.”