The Fight Against the "Very Real" Threat of the Record-Breaking Table Rock Fire

The largest fire in Upstate South Carolina history also burned more than 500 acres in Transylvania County. If not for a shift in the weather and the work of fire crews, it could have been a lot worse.

CEDAR MOUNTAIN — Robb Davis, the assistant regional forester who led the North Carolina Forest Service’s fight against the Table Rock Fire, isn’t given to dramatic talk.

Driving past fire-blackened slopes on a dirt road along the South Carolina state line Tuesday afternoon, he provided a detailed account of the nearly week-long battle against advancing flames in restrained, professional terms.

Snuffing out blazes was “suppression,” the twigs and leaves of Tropical Storm Helene deadfall were “lighter fuel classes” and the troops of firefighters, along with their trucks, hoses and bulldozers, came out as “operational resources.”

So it was all the more striking when Davis allowed that, yes, the main body of the fire was burning hot and fast when it crossed the state line on the afternoon of Thursday, March 27, that more than once crews had to retreat from the flames, that he was, if not scared, at least deeply concerned — “My senses were very heightened,” he said — and that, when the weather was at its driest and the wind at its highest, he fully expected the fire to reach homes and, possibly, upend lives.

That threat was “very real,” Davis said.

“In fact, if you would have asked me on (March) 27th or 28th if we would have had firing operations around structures, I would have said, ‘100 percent, yes,’ ” he said.

If residents didn’t already know it from the evacuation orders and the smokey haze that enveloped Brevard in the last week of March, Davis confirmed that Transylvania County narrowly escaped a major natural disaster less than six months after being hit with devastating winds and flooding from Helene.

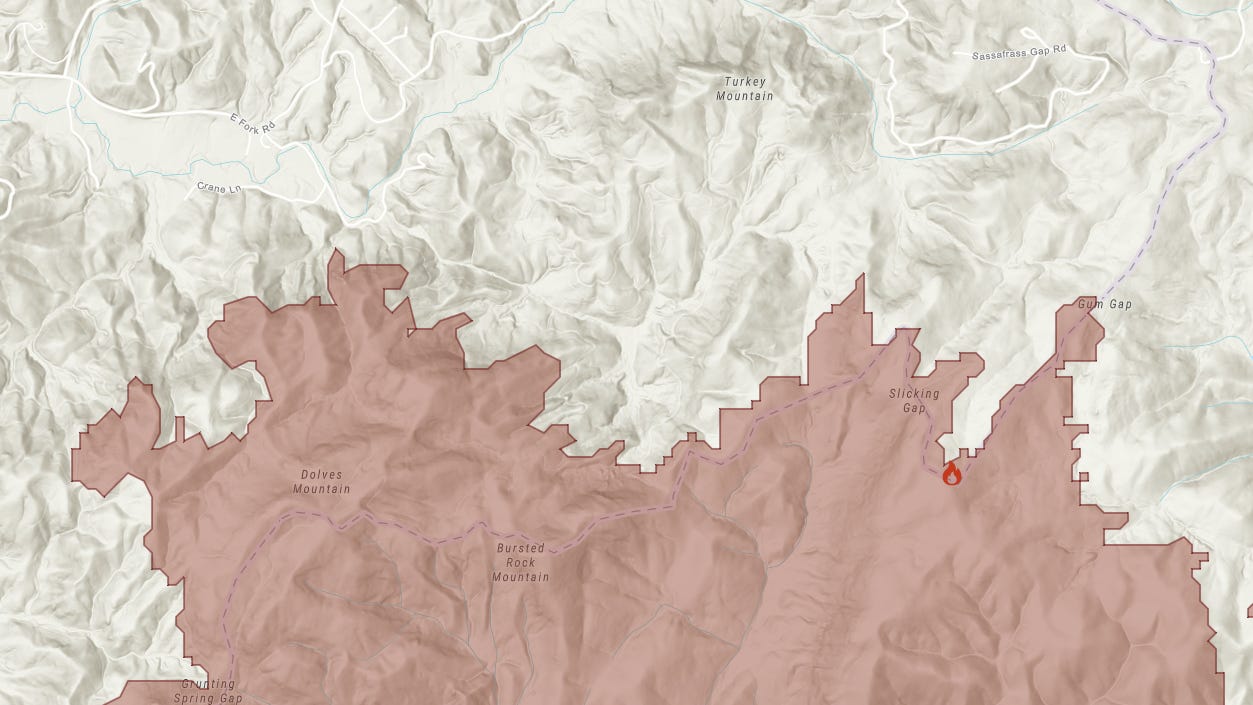

The Table Rock Fire, which consumed nearly 14,000 acres — including more than 500 in North Carolina — was the largest in the history of Upstate South Carolina.

Its cost to the that state’s Forestry Commission was more than $8 million, a number that is not only sure to grow, but that doesn’t include the expenses incurred by the dizzying number of other agencies that contributed airplanes, trucks, heavy equipment and a total of more than 500 firefighters and support staffers to fight what was, for several days, the highest priority wildfire in the nation.

Though their exhaustive efforts have been lavishly praised by grateful residents, this work might not have been enough to save homes if not for improved weather and the damper, north-facing slopes the fire encountered once it crossed the state line, Davis said.

The threat from such blazes will grow in the future, according to scientists who have tracked the increased frequency of wildfires and the rapid residential development of natural areas in the Southeast, as well as, of course, the ever-warming climate.

Table Rock’s consumption of forest debris and flammable understory plants should reduce the likelihood of a destructive wildfire in southern Transylvania for the next three to five years, Davis said, but in the long term the risk will be heightened by other factors.

If not addressed, chronic staffing shortages and antiquated equipment will continue to hamper the Forest Service’s ability to carry out preventive measures such as conducting prescribed burns and bolstering fire lines, he said.

And the large limbs and trunks of trees felled by Helene that were too green to burn in this fire represent a potentially massive fuel source for future blazes.

“The thing we have to concern ourselves with this year and the next 10 years is all the Helene damage laying on the ground,” he said.

Actually, said Davis, 41, correcting himself, not just 10 years, but “probably the rest of my career.”

On the Battle Line

The array of agencies that responded to the fire is too long to fully list but included the NC Forest Service, Transylvania Emergency Services, every one of the county’s fire departments and the federal “Blue Team” emergency response group.

Though Team members didn’t arrive in Transylvania until after the worst of the fire threat had passed, said Davis, who put in nearly a week of 17-hour days as the incident commander in North Carolina, they relieved exhausted personnel with sophisticated firefighting equipment and highly trained crews from as far away as Nevada.

“They were of great benefit, for sure,” he said.

At its peak, the operation in North Carolina employed about 150 firefighters and other workers stationed at the Connestee Fire Rescue headquarters on East Fork Road.

The Forest Service took the lead on bulldozing fire breaks and setting fuel-consuming “backing fires” intended to move south to meet the wildfires advancing northward, Davis said.

County firefighters, meanwhile, were stationed near homes, standing by with pumper trucks and blowing leaves, twigs and other flammable debris from almost all of the 758 structures in the evacuation zone south of East Fork and west of US 276.

Local firefighters were also called in to extinguish a spot fire that flared up north of the fire line and quickly consumed about a half acre in the darkness of early Friday morning, Davis said.

“It probably quadrupled in size in about an hour,” he said, pointing to the site of the spot fire. “Four or five of them came up here and just knocked it out.”

Earlier in the week, a crew led by Davis bulldozed a fire line — partly on lanes left from a previous timber harvest — from Gum Gap east towards 276, sealing off the Sherwood Forest and Stone Lake communities.

That line could have been bolstered along its entire length with a backing fire if a large wild blaze had come closer.

That this never happened could partly be attributed to the work of a state crew that set a small controlled fire near Gum Gap, which is about two miles due south of Sherwood, creating a blackened “mitten” of burned forest to contain a “small finger of wildfire” working its way up from the south.

This left the main battle line west of Gum Gap, along a rocky, rutted road deep in Headwaters State Forest that also serves as a spur of the Foothills Trail.

Driving east on this path from an extension of Dolly Masters Road, Davis’ four-wheel-drive pickup truck passed mountain faces on the right blackened by a backing fire. On his left was the mostly unburned forest where county firefighters had put out the spot fire.

Then he came to the scorched landscape where flames crested the ridge near Dolves and Bursted Rock mountains and consumed the steep slope to the north before stopping just a few hundred feet from the homes in the deep valley on Crane Lane and Streamside Drive.

Davis had one more plan that didn’t need to be executed, cutting a fire line behind those homes, the potential starting point of another backing fire.

Even so, he expected that the tools of fighting blazes in the forest — bulldozers and backing fires — would soon give way to the hoses and fire engines employed by local crews to prevent and fight house fires.

This scenario never played out — not primarily because of the firefighters’ work, though that certainly slowed the fire’s advance, but because of factors beyond their control.

The fire burned slower as it moved downhill from the 3,000-foot plus elevation of the mountains into the valley. These north-facing slopes receive less sunlight and retain more moisture than hillsides facing other directions, he said. Then there was the arrival of more favorable winds and higher humidity on Friday, the light rain on Saturday and heavier showers Sunday.

“We got a lucky break with the weather,” he said.

Fire Weather

But the weather leading up to and during the fire’s first days was anything but lucky.

High winds in the weeks preceding the fire’s ignition in Table Rock State Park dried the landscape and, later, drove flames north towards Transylvania.

The humidity dropped as low as 14 percent as the blaze progressed, according to Douglas Wood, communications director for the South Carolina Forestry Commission.

The total March rainfall measured in Brevard before the last two days of the month, 2.4 inches, came to less than half the historic average, according to a North Carolina State University website that compiles statewide data from the National Weather Service and that also showed a pattern of below-average precipitation in the six months since Helene’s deluge.

An array of factors contributed to this year’s “active fire season” in North Carolina, Corey Davis, the assistant state climatologist, wrote in an email, citing debris left by the storm and a La Nina weather pattern “that shifted jet streams and storm tracks mostly away from North Carolina.”

But he also pointed to persistently high daytime highs in March throughout the state, before concluding that “while climate change wasn’t the sole factor behind our recent fire activity, it's easy to see how those warmer temperatures and higher evaporation rates ramped up the risk during that event.”

Corey Davis also provided a link to a 2015 study showing a predicted 50 to 100 percent increase in the length of the season carrying a risk of “very large fires” in the North Carolina mountains by the middle of the century.

Another study, meanwhile, found that the number of wildfires in the East had doubled in the years between 2005 and 2018 compared to the previous two decades and documented an especially rapid increase in the fast-growing Southeast.

Which not only shows that the threat of wildfire, typically associated with the arid West, is increasingly imminent in the East, but also leads to the subject of residential development in the WUI (pronounced WOO-ee), the Wildland-Urban Interface.

The number of homes in these natural landscapes, often near state and national forests and parks, increased by 47 percent nationwide between 1990 and 2020, according to the US Forest Service website.

Transylvania is a prime example of this pattern, according to an interactive map on the site showing that 98 percent of the county’s housing is located in the WUI.

Considering the number of homes in solidly urban neighborhoods of Brevard and Pisgah Forest, that percentage could be disputed. But there’s no doubt that evacuated neighborhoods such as Big Hill and Sherwood Forest lie firmly within the WUI, and that many of their residents fit the website’s general description of Interface denizens as people who “love to live near forests, lakes, open space and scenic beauty.”

The downsides of the growing crowd giving in to this allure: it makes bulldozing preventative fire lines and conducting controlled burns more difficult and expensive; it increases the urgency and expense of fighting fires; it precludes the possibility of a practice receiving increasing support from forestry scientists — allowing potentially beneficial wildfires to burn freely and consume excess accumulations of fuel.

Overall, according to the US Forest Service site, “WUI expansion increases the number of houses at risk from wildland fire and makes it more likely that wildland fires will occur.”

The Obstacles to Prevention

Full disclosure: I’m one of those WUI residents, as is one of my neighbors in Sherwood, Gus Napier, who owns a primary residence and a guest house in the community’s southernmost corner, closest to the Table Rock Fire line.

He echoed a sentiment nearly universal in the neighborhood — deep gratitude for the firefighters’ work in protecting homes, removing flammable debris and allowing residents to briefly return after evacuation to retrieve valuable possessions.

“Their presence on our street was pretty heavy. They let us in, they let us out, and they were always cordial and friendly and helpful,” said Napier, 86.

“They worked awfully hard . . . They were terrific.”

Robb Davis hears such thanks and praise “every time I get out of the truck,” he said. “It’s very humbling.”

But as proud as he is of the work of all the firefighters who battled the Table Rock Fire, he wishes more could be done to prevent the need for such a massive emergency response.

That includes prescribed burns, outreach to inform residents how to make homes resistant to wildfire, and strengthening fire lines, he said. “I’d really like to beef up some of those contingency lines so we can get engines in there, which really could have helped us with some of our backfire operations.”

That takes staff, modern equipment and money, he said, all of which are in short supply at the state Forest Service.

It’s a message that the state Commissioner of Agriculture, Steve Troxler, took to lawmakers last week, citing the need to fill about 100 vacant positions in the Service and replace aging helicopters and bulldozers.

“The biggest takeaway from (the Table Rock Fire) in my opinion is that, with the reduced employment and retention rates in the Forest Service, we have to do something about it or this is just going to be perpetual,” said Davis, referring to the spread of wildfires.

“The ideal situation,” he said: “We spend more time preventing these fires as opposed to fighting them.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Dan, congrats on an impressively thorough and detailed reporting job. As you know, I live just south of the state line. Our home was two miles from the eventual western edge of the Table Rock fire. I appreciate learning so much from your article about the logistics of the fire fight. Well done! Also ... the irony of how homes in the WUI (mine included) both prevent obstacles to firefighting and add urgency to the battle to extinguish wildfire...sobering.

Wonderful reporting Dan. By far the best story I’ve read on this Fire. Thank you for all the great work you do.