Plenty of Money or Not Enough? Schools, County Battle over Funding

Transylvania School Board members talk about roof leaks and a $35 million backlog in needed improvements across the district. County commissioners cite high rates of local spending on schools.

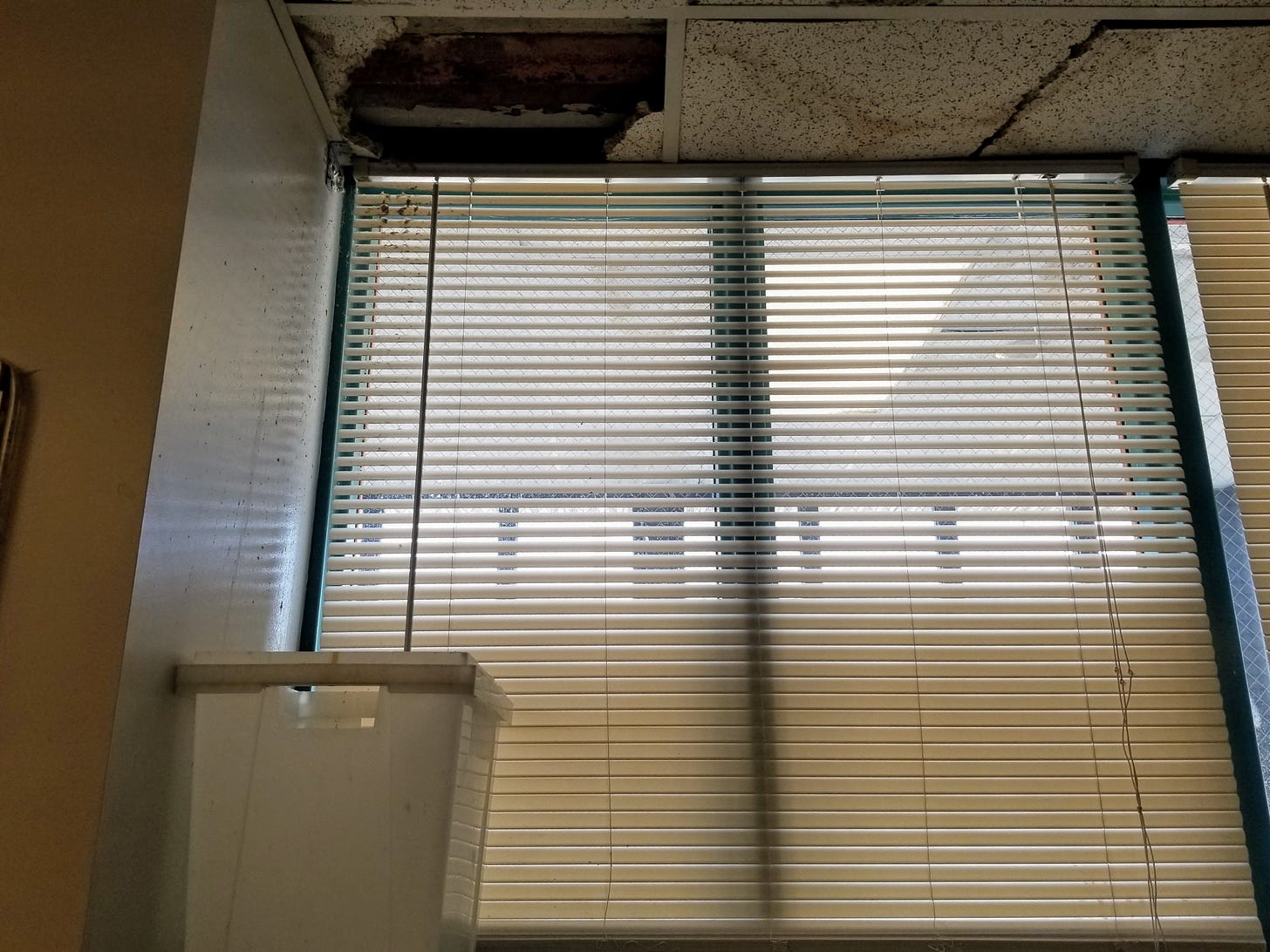

BREVARD — Rosman High School Principal Jason Ormsby pointed down to the water-stained carpet in the school’s front office and then up to a space above the ceiling tiles where buckets had been placed to catch leaks.

During heavy rains, a custodian arranges trash cans on the floor to contain the remaining drips and a receptionist recently wore a raincoat during school hours to protect against spattering moisture.

So, when it comes to signs of the school’s leaking roofs, this is ground zero?

“No, this is ground 100 and zero. One of many,” Ormsby said this week, and on a subsequent tour of the campus, he and incoming Rosman Middle School Principal Julie Queen showed off a wide range of causes and results of the chronic water intrusion in both schools:

Flat and repeatedly patched roofs, a quarter-inch crack between new and old sections of the schools, stained and crumbling ceiling tiles, blistering paint, buckets permanently perched next to window frames and a corridor called the “obstacle course” because of the number of trash cans set out during storms.

Because these fail to catch all the water falling onto the hallway, Queen said, “during the last couple of heavy rains we actually had to close it down.”

The roofs are one recent flashpoint that has helped make the always-contentious relationship between the Transylvania County School Board and the County Commission, which holds the power to fund it, more contentious than at any time in recent memory, said Board Vice Chair Ron Kiviniemi.

“I’ve been on the Board for almost 10 years now and it’s at the lowest point it’s been,” he said.

The underlying issue is the stalled, voter-approved $68-million renovation project for Brevard High School and Rosman High and Middle schools. The board asked the county to sign off on contracts needed to move forward with this work at the end of January, and the Commission has not yet taken action — though a discussion of the topic has been placed on the agenda for the upcoming meeting on Monday.

Former School Board member Alice Wellborn’s reminders of this delay during public comment have become almost as standard at the start of Commission meetings as the Pledge of Allegiance.

More recently, Board members have expressed growing frustration at a lack of funds for smaller but still expensive improvements, such as the roof replacements at the Rosman schools that would cost a total of $400,000.

Thanks to chronic underfunding for such work, School Board Chairman Tawny McCoy wrote recently in a letter to commissioners, the school has accumulated a backlog of $35 million in facility needs — not including the major renovations at Brevard and Rosman.

“I’m about ready to pull my hair out, and I have very little left to pull,” Kiviniemi said at the Board’s June 6 meeting.

The Commission, struggling to find money for other pressing projects such as a new courthouse and a new campus for Blue Ridge Community College, is pushing back.

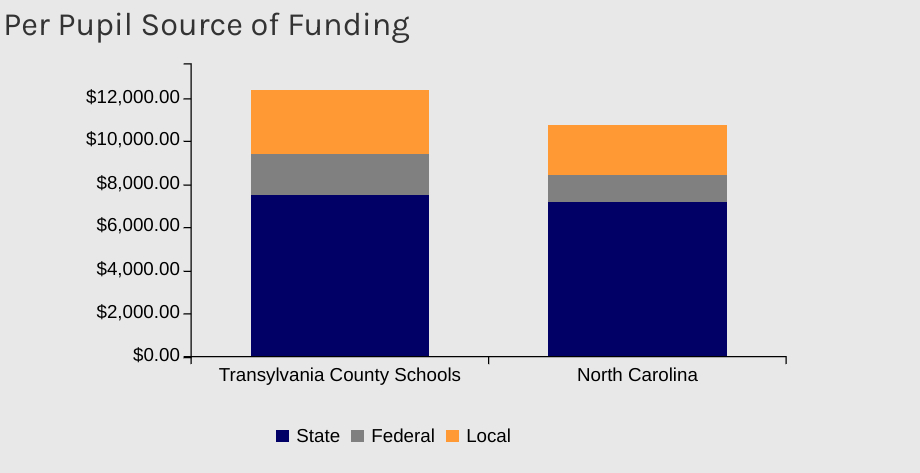

And on Monday, Commissioner Larry Chapman brought home his point with a statistic about the county’s contributions to education: Transylvania County has the fourth-highest per-student funding among the state’s 100 counties, he said.

“I’m proud of what this county has contributed to the education of our children and the numbers show it,” he said.

Taxes and Spending

McCoy’s letter, sent June 6 with the unanimous backing of the Board, took issue with some components of the county’s $13.1 million contribution to operational funding, saying it was inadequate to cover items such as state-mandated salary increases or improvements to school security.

But the biggest shortfalls result from what Board members say is the inadequate $2.1 million allocated in the county’s recommended budget for capital spending, which must cover both new equipment and school improvements, the letter said. This leaves out, along with money for the roofs at Rosman, $200,000 to repair leaks at Pisgah Forest Elementary School, $125,000 for new paving at Brevard Middle School and $115,000 to cover the increased cost of replacement computers.

In recent weeks, Kiviniemi has pushed two main arguments about the county’s process of deciding the schools’ budget.

Historic county funding for schools’ capital needs has been the minimum allowed by state law, derived strictly from mandated percentages of local sales taxes, he said Monday.

“I think the citizens of Transylvania County would be surprised to find that there is no county money coming for capital repairs and improvements to schools other than what (commissioners) are required to share in sales taxes,” he told the Commission.

That’s not quite accurate, said County Finance Director Jonathan Griffin, pointing to a contribution in property tax revenue needed to cover some school capital costs in 2019.

“There was a time, fairly recently, when property taxes were necessary to close that gap,” he said.

But Kiviniemi produced a document showing that if the county had regularly matched schools’ requests for funding, it would have amounted to an additional $11.6 million to address needs from 2005 through the end of the current fiscal year.

Money to pay for regular repairs, he said, would have “absolutely” cut into the current backlog of needs.

“We would have been able to keep the roofs repaired and the bathrooms remodeled,” he said.

He also criticized the county’s 2020 decision to take control of individual school improvement projects rather than leaving those decisions to the Board.

Yes, this is allowed by state law, he said, “but it gives the County Administrator (Jaime Laughter) the power to arbitrarily delete some items. For instance, I would point to the two roofing projects.”

In this year’s budget discussions, Laughter, who was out of town and unavailable for comment this week, has repeatedly stressed several points. No county function received all the money it requested in the upcoming budget, which the Commission is set to approve on Monday.

Raising property taxes is the only feasible means available to commissioners to collect additional revenue, she has added, and income from this source is limited by a stagnant tax base that relies heavily on residential properties.

The schools also have the option to request amendments to the projects the county selects, Laughter said in a meeting in March. The Commission voted in 2020 to choose projects for the board, said then-Commissioner Page Lemel, because the schools repeatedly failed to complete budgeted work.

“You would seem to see the same projects carry over year to year,” she said.

And Griffin said this week that the roof replacements at Rosman were put on hold because of uncertainty about the major renovation of the schools, the latest plans for which call for the demolition of the current middle school building.

“We’re still trying to figure out what’s happening at that campus,” he said.

But the current high school will serve as the new middle school after the renovation project, Ormsby said. And it is not set to receive any significant improvements under revised plans the Board agreed to last year after bids for the original proposal came in $18 million over budget, Ormsby said.

It has also been four years since voters approved the project, he said, and there is still no scheduled start date for the work.

“The bond passing has put us in a bad way because we’re on hold,” he said.

Fourth in the State

The school funding numbers cited by Chapman — and echoed by Commissioner Teresa McCall — focus on operational spending rather than meeting capital needs.

Still, they said, it strikes back at the argument advanced by Wellborn and others, that the county is neglecting its duties to fund schools.

“I’m still kind of hung up on comments about our dereliction of our duties,” Chapman said, before mentioning the county’s high ranking for school funding.

According to the state Department of Public Education website, the county’s per-pupil funding in fiscal year 2020-21 was $12,338 compared to $10,753 statewide.

A report recently released by the nonprofit Public School Forum of North Carolina shows a local contribution of $3,923, resulting in the fourth-highest ranking commissioners referred to. The average local teacher supplement, the amount added to the state’s base salary, is $4,118 in Transylvania, second in Western North Carolina to only Buncombe County, the report says.

One of the reasons for high per-student costs, said School Board member Kimsey Jackson, is an aging network of schools built for a larger student population, which has declined from more than 3,500 in 2013-14 to less than 3,300 during last school year, according to the department of instruction.

“We are spread out and we operate too many schools and that increases our personnel costs a fair amount,” Jackson said.

Schools Superintendent Jeff McDaris said that the funding covers a wide range of classes and extracurricular activities offered in Transylvania compared to other counties its size and can be partly blamed on accounting practices. Some counties fund school resource officers and nurses directly, for example, while in Transylvania those positions are part of the schools’ budget.

And if some people see consolidation of schools as a way to reduce spending, he said, they should realize that carries its own costs.

“If you decide you want to combine the high schools and build one shiny new high school, that’s going to cost money. If you decide you want to cram everybody into one existing campus at Brevard High School and fix it up so that everybody can be there, I got news for some people. That’s going to cost money too,” he said.

The best way to increase enrollment, he said, is to attract industry and address the shortage of affordable housing, so more young families can afford to live in Transylvania.

“The schools didn’t cause those issues,” he said, of the county’s low wages and high housing costs. “I want to be more than just a playground for visitors.”

Communication that Hasn’t Happened

Nearly everybody interviewed for this story cited one source of the perennial friction between the Board and the Commission — North Carolina’s unusual system that gives counties funding power over schools.

If that is beyond the control of local officials, the other most commonly mentioned issue is not: a lack of communication between schools and the county.

McDaris said this week he had offered to meet with Laughter when he sent this year’s budget request. Laughter said in March that she had repeatedly sent the same message to schools.

“We have expressed interest in sitting down to go line by line with our finance director and myself for the past five years, every year, and we have not had that meeting,” she said.

They should, said Jackson.

“If I had my way, Jaime (Laughter) and Jeff (McDaris) would meet at least once a month and include the finance officers sometimes. And the two boards should meet once a quarter and talk to each other, and that's not done.”

Commissioner David Guice also called for more civil discussion at Monday’s meeting: “It does us no good to yell at each other. It does us no good to point a finger at each other. It does us no good to blame each other.”

He agreed with Chapman that school operations are well funded, he said in a follow-up interview, but also pointed out that the Commission is legally required to address maintenance issues.

“That’s great,” he said of the county’s high per-student funding. “But that doesn’t meet the needs of our schools . . . and we have to find a way to meet those needs.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Wow. Sobering article, Dan. Thank you.