Longtime Employee Helps Keep Harris Hardware "Real"

Robert "Bob" Williams is more than a clerk at the famous downtown hardware store. He's its resident historian and an "essential" guide to its dizzying array of merchandise.

BREVARD — If you can forgive the cheap wordplay, let’s say the nails pounded into Harris ACE Hardware’s century-old floor nailed down Robert “Bob” Williams’ decision to move to Transylvania County.

In the summer of 1997, as Williams was wrapping up his career as a micropaleontologist in New Orleans, he and his artist wife, Barbara, arrived in Brevard on a scouting trip of future retirement destinations.

She visited galleries. Williams, 81, who is as moved by orderly bins of nuts and bolts as football fanatics are by long, arching spirals, made a beeline for the hardware stores.

At Harris, his eyes caught the oiled wooden floor and the row of shiny nail heads, which he identified as a time-tested, time-saving tool for measuring rope.

“One foot, two feet, three, four, five . . .” Williams said last week near the rear of the store, pointing to the first few markers in a middle aisle. “Then every five feet until you get up to the front window. So, if you want to measure some rope, I can get it for you.”

When he and his wife reunited, the conversation went something like this, Williams recalled:

“She said, ‘I’m getting some good information from people in town. I think this is where we want to live.’ And I said, ‘I agree.’ ”

So, probably nobody appreciates Harris, which has occupied the same building on 87 W. Main Street since 1972, as much as Williams, who’s spent much of the last two decades as a clerk camped out in his favorite aisle in the store, the one on the left as you walk in, the one with all the tools.

Christmas being the season to celebrate local shops, it’s a good time to toast maybe the city’s most recognizable retail employee.

Williams is the guy in the tape-measure suspenders who looks enough like one of Santa Claus’ short, stout helpers that a white-lined spot behind the store is reserved for “Gnome Parking Only.”

In keeping with the holiday theme, his 2000 Chevrolet Asto minivan is so vividly green that it is nicknamed “the Pistachio.” His work T-shirt, advertising Benjamin Moore paints, is bright red.

And as a sign of his devotion to the store, he recently compiled an exhaustive history of the Harris building that fills much of a three-inch thick binder at the Transylvania County Library.

But Williams is hardly the only county resident to appreciate Harris, and longtime Brevard City Council member and Transylvania native Mac Morrow was one of several people interviewed who described the store as “real.”

If it has become a destination for nostalgia-minded tourists, that’s only because it never catered to them. In a downtown increasingly full of stores offering merchandise visitors might want, Harris stands out for being packed floor-to-ceiling with items they actually need.

It’s a throwback to the Brevard of Morrow’s youth, he said, when the city center was a hub of essential commerce, adding that he had recently picked up a pipe fitting at Harris for a project at his nearby employer, KEIR Manufacturing Inc.

“It’s a practical matter for those of us who live and work here, to have that supply chain available locally,” he said. “It’s what you need to make the town authentic, to make the town relevant.”

It Started with “Dad”

How much does Williams like stores such as Harris?

His first trip there was in keeping with a lifelong habit.

“Whenever I go from point A to point B, I pretty much hit every hardware store in between.”

Why does he like them?

He answered by describing his childhood in the small, northeastern Pennsylvania town of Nesquehoning, telling stories in a tone of low-key amusement, confident his listener will find them as fascinating as he does.

His father was a high school shop teacher who, nearly every evening, descended into a basement workshop with young Robert at his heels.

“He’d sit me down on a big barstool at the end of the workbench and explain everything he was doing,” Williams said. “When I got to first or second grade, I knew what all the tools were and I knew how to use them and I knew how to sharpen them.”

Williams later accompanied his father when he drove to side jobs as a carpenter or painter, his 1936 Chevrolet coupe loaded down with tools and paint cans, with ladders on fender-mounted racks.

“We’d just barely make it up hills and then go like a bat out of you-know-what on the other side,” he said.

The father demanded that his son deliver lunches to his painting jobs and clean up after their nights in the workshop, sweeping shavings from the floor, lightly oiling the tools and stowing them in their prescribed spots. It was Robert’s responsibility to assemble supplies needed for upcoming jobs and if he forgot to include, say, a spare hammer, he’d be scolded by “Dad,” he said.

“He’d say, ‘What happens if that hammer breaks? I have to come back home to get another one.’ ”

When asked if he really enjoyed this role, serving as unpaid help for a taskmaster father, Williams suddenly turned serious.

“I loved every minute I spent with him,” Williams said emphatically. “I was learning. It was fun.”

29 Mules

Williams went on to earn a masters’ degree in paleontology from Pennsylvania State University and embark on a career analyzing soil removed by the drilling operations of a major oil company.

“I used a microscope to identify fossils,” he said.

He later added history to his researching skill set by documenting his family’s genealogy. Then, starting in late August, he devoted more than a month of evenings and weekends to mining the Library’s Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room newspaper archives for stories about the Harris building.

He just wanted to learn more about the history of hardware in Brevard, he said, wanted to flesh out stories he’d heard from its previous owners — founder Mabry Harris, who died earlier this year, and his son, longtime Brevard Mayor Jimmy Harris, who took over the store in 1988 and who, in declining health, sold it to Sapphire-based McNeely Companies last spring.

As Mabry Harris had often told him, Williams said, there really was a fire at the store’s location, a big one, the extent of its damage summed up by the following subhed above a story in the Jan. 12, 1923 edition of the Brevard News:

“29 Mules Burned to Death — Dozens of Automobiles — $60,000 Blaze”

The destroyed structure was called the King Building, after A.H. King, who founded a Brevard Ford dealership in 1913. By the time of the fire, he’d sold it to other owners, who also operated a livery stable in what is now Harris’ basement.

Though many horses were saved, the death toll of mules was likely to climb, the story said. “There are half a dozen that were so badly burned they will probably die.”

A new owner of the dealership, C.E. Lowe, built the current structure, and its completion in November of 1924 warranted a celebration featuring the new “Municipal Band,” according to announcement in the News, which urged readers to stop by and “congratulate Mr. Lowe on his achievement.”

Among the enterprises that later operated in this space, according to Williams’ summary of his research, were furniture and feed-and-seed outlets, a skating rink and the Brevard Battery Co.

Also, one previous hardware store — apparently part of a chain with which Harris carries on such a heated rivalry that, rather than say its name, Williams formed an ‘L” with his thumb and forefinger in front of his ball cap.

Lowe's was founded in Wilkesboro in 1921 and was beginning to build a national presence in the early 1960s, when newspapers referred to what is now Harris as a “Lowe’s Brevard Associate Store,” Williams wrote.

“I think that’s how they started out,” he said of the Lowe’s chain, “and they were here for two years.”

You Need a Guide

Such historical knowledge allows Williams to add extra information, bonus content, to the home-improvement and inventory expertise he needs to do his job.

Think of Williams not as a clerk, but as a guide leading clients through the store’s 6,000 square feet of territory to two elusive destinations — the location of a single desired item in a business stocking well over 12,000 of them and the finish line of a project’s completion.

Many customers who come in can only describe the job they hope to complete, said store manager Seth Batchelder; Williams is able to tell them how to do it, the tools or supplies they need and where to find them.

Especially since Williams took time off during the Covid-19 pandemic, Batchelder said, he has come to realize that “Bob is essential.”

“It was rough without him. He’s the go-to,” said Batchelder. “Bob is Bob. He’s a character and curmudgeon. He’s just a beautiful person and we love him.”

Williams, in turn, sees beauty in, for example, the brick pillars in the store’s basement that survived the fire. They now outline storage bays stacked with bags of pool chemicals or galvanized steel tubs. In the old livery, he said, they anchored stalls housing horses and mules.

Climbing the wooden stairs to the first floor, he can tell you they have been there for precisely 99 years.

“You can see how they are cupped and grooved,” he said of the steps. “That’s just wear and tear since 1924.”

On the store’s first floor, all that remains of the previous structure are the walls, the brick of the eastern one covered with fake wood paneling barely visible behind a long, ceiling-scraping row of air conditioning filters.

Which gets us back to Williams’ main job.

He knows what few outsiders could tell by looking up at those filters, that they are carefully ordered by size. Down at eye level, he instantly locates a specific lag bolt stored amid a row of 12 plastic drawers stacked 12 high.

His interviewer is amazed by the variety. A total of 144, right?

No, he said, pointing to four other similar displays of nuts, bolts and screws.

“Times five,” he said. “That might get you close.”

The ability of Harris’ clerks to navigate this maze of merchandise is why Stephanie Smith, an interior designer, said she usually makes the store her first hardware stop.

“I appreciate that I can walk to the front desk, tell them what I’m looking for and they can point it out in about five seconds,” she said last week, when she arrived in search of wood screws to anchor a door to a jamb.

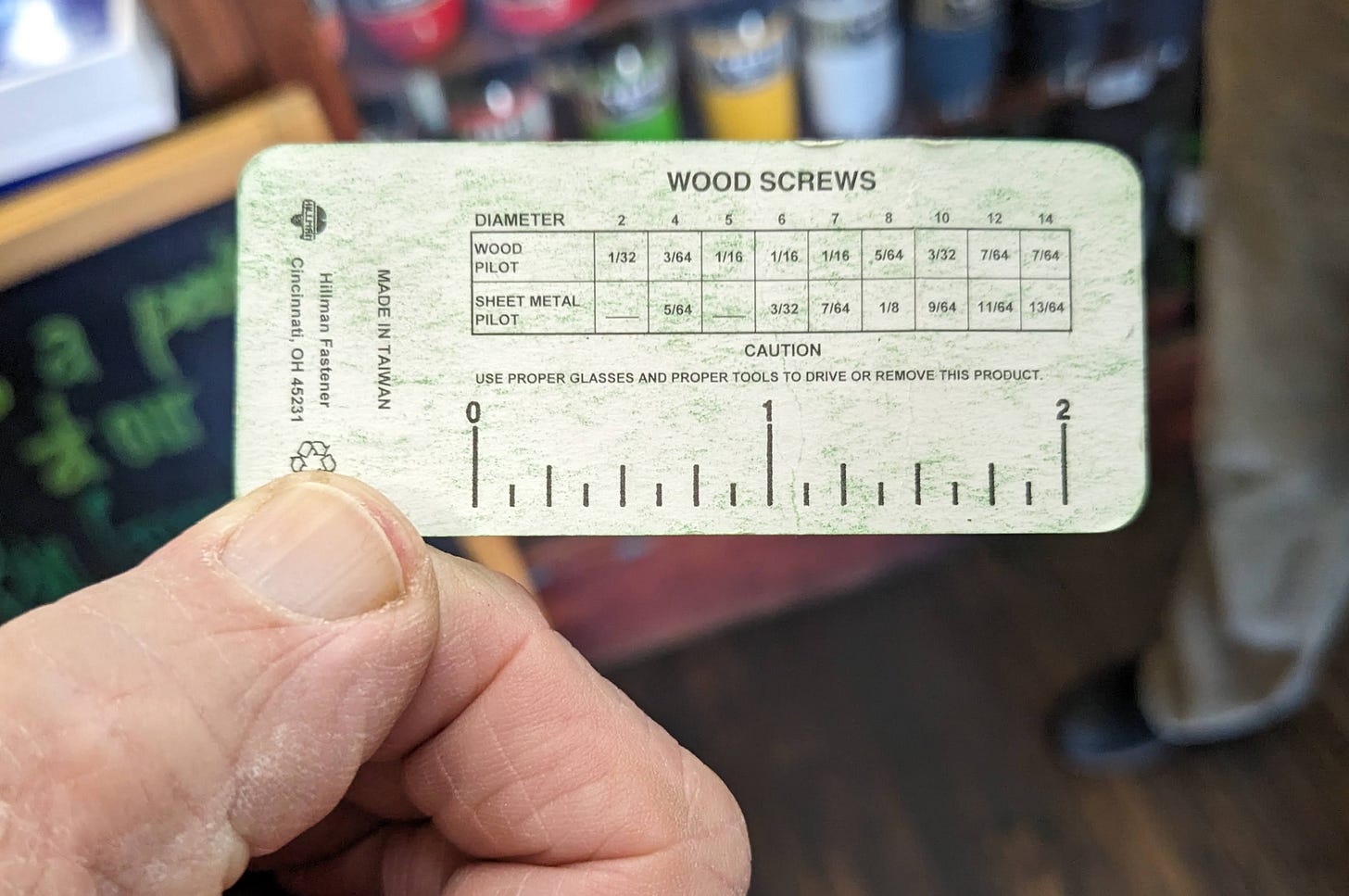

Williams couldn’t help her without seeing the hinge, he said. But he did take the time to explain she would need to drill pilot holes, and he then produced one of the tiny charts formerly included with packages of screws showing the correct diameter of such holes for each size of fastener.

“You don’t have to bring the door, just the hinge,” he said, joking. “That’s what I need to see so I can tell what screw goes in there, and I can tell you the size of the pilot hole.”

After she had left, he acknowledged that his time with her wouldn’t lead to a big sale. Neither did his extended conference the previous day that hooked a man up with a nut and bolt costing a total of 65 cents.

“But you know what? On the way out he might get something else, and he’s going to come back because he got really good service really quickly,” Williams said. “And he’s going to look for Bob.”

Not Really the Nails

Which pretty much sums up the store’s business strategy, Batchelder said.

Customer service has allowed it to maintain its niche in the era of a chain hardware stores, he said, a niche it has continued to occupy since its sale to McNeely, which controls a sizable chain in its own right — more than a half-dozen ACE Hardware stores in the western Carolinas.

The company committed to operating Harris in its current location “mainly because of the history of it,” said one of the company’s owners, Sherry Whitmire. “It’s a fixture downtown and it would be a disservice to take that away.”

What about when McNeely completes its plan to open a large, full-service Ace at the site of a former bowling alley on Rosman Highway? The only change Batchelder foresees at Harris, he said, is the ultimate destination of customers like Smith — the ones who come to his store first and can’t immediately find a desired item.

“They say, ‘Please don’t send me to Lowe’s,’ and we’ll be able to tell them we have what they need right down the street,” he said.

Williams sometimes seems happily amazed that this is really his job, helping customers, joking with them, chatting about the pros and cons of various approaches to their projects.

“I love coming to work,” he said.

And when you look back at his long fascination with hardware, you realize its not just about drills, hammers, nuts and bolts or even the rope-measuring nails. It’s about the accompanying culture, a culture populated by his father and the Harrises, by his coworkers and customers.

“It’s the people,” he said.

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

👍😊

Bob Williams is of my favorite characters and friends! Thanks for this beautiful article.