Logging Can Renew Habitat. And, A Lawsuit Says, Destroy It

Three years after controversial logging at Headwaters State Forest, a more diverse habitat is emerging. But the larger debate includes a suit challenging harvests in national forests.

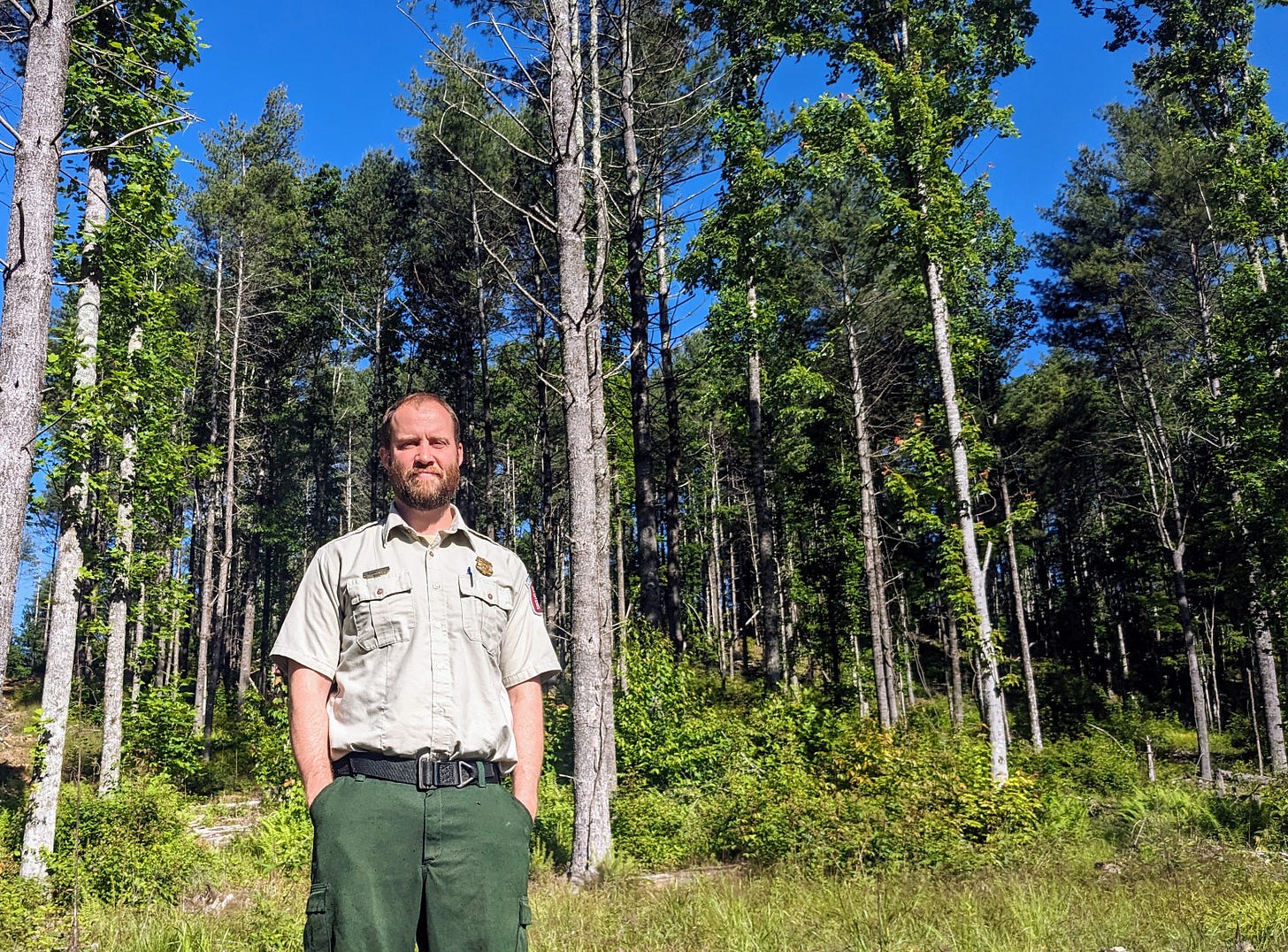

CEDAR MOUNTAIN — Lee Wicker would have been walking in deep shade a little more than three years ago, when the slope in Headwaters State Forest he climbed Wednesday morning was covered by a crowded stand of 40-year-old white pines.

Clearcut logging completed in early 2021 reduced this tract to a denuded, slash-littered landscape. Even Wicker, the North Carolina Forest Service forester who managed the harvest, acknowledged that, at least to the untrained eye, the initial results “looked terrible.”

But now, in bright sunshine, he passed shoulder-high shortleaf pines and clusters of white oaks planted in the cleared land. He pointed to the surrounding natural growth of blackberry bushes, pokeweed and the seedlings of birch and black locust — the foundation of a new forest already feeding deer, turkey, songbirds and pollinating insects.

“This is a buffet,” Wicker said. “To me, this is a success story in tree planting and the creation of beneficial habitat.”

The logging at Headwaters, which included both the 51-acre clear cut and the thinning of more than 74 acres near Glady Fork Road in southern Transylvania County, became a local flashpoint in the much larger debate about timber harvests on wild lands.

Nature lovers expressed outrage at what they saw as the destruction of a mature forest, and a prominent if controversial California ecologist, Chad Hanson, proclaimed clearcutting indefensible and advocated for allowing natural succession of the habitat.

“I suggest leaving it alone,” Hanson said at the time.

But what may have appeared to be a natural pine forest was actually an old pine plantation, a state forester said, and the stand designated for clearcutting was too old and unhealthy to be salvaged. He said the growth that replaced it would be far more diverse and vibrant, which you could see for yourself if you came back in a few years.

On that return visit this week, Wicker was able to show the promised regeneration, and representatives of environmental organizations interviewed said it shows that under the right circumstances clearcutting can be, as one of them put it, “good stewardship.”

“We’re not opposed to all logging in the national forests,” said David Reid, national forest issue chair for the North Carolina chapter of the Sierra Club. “We supported reasonable logging targets that would achieve a balance.”

A Logging Lawsuit

Defining that balance is the crux of the broader debate about logging, including a dispute over the recently finalized Nantahala-Pisgah Land Management Plan that Reid referred to in his comments.

Last month, the Sierra Club and three other environmental groups filed a federal lawsuit against the US Forest Service, claiming that the dramatic expansion of logging the plan allows in these national forests would degrade the habitat of four endangered bat species.

Though lawyers for the Service have not yet filed a response to the suit, an analysis completed as part of the years-long planning process was intended to carefully address the impact of logging. It not only accounted for the future health of threatened and endangered species, this study’s narrative said, but considered impacts on “an additional 689 plant and animal species . . . based on the request of the public or other species experts.”

Reid’s view, on the other hand, is that the expansion of harvests was the result of “political and bureaucratic pressure.”

And the plan definitely doesn’t do enough to protect bats, according to the suit, which states the allowed “tree clearing can eliminate multi-generational roost trees or favored foraging areas that bats return to year after year.”

Some of the bat species are also highly sensitive to the size of openings in the forest, said Josh Kelly, public lands field biologist with Mountain True, another party to the suit. Northern long-eared bats, in particular, tolerate only small openings, he said, and avoid large clearings created by logging operations.

It’s a prime example of the nuances required for a responsible approach to timber harvests, he said.

“What Mountain True really objects to is the (logging of) 100,000 acres of Nantahala and Pisgah national forests that are documented to have really high values for very unique and rare species of wildlife.”

Deer, Songbirds and Pollinators

What about the logging in Headwaters?

Andy Tait is co-director of EcoForesters, a group that promotes responsible logging practices, of which the work at Headwaters is a prime example, he said.

One key consideration is the type of forest being re-established. “Shortleaf pines used to be very very common in the natural landscape.,” he said. “It’s an important tree for wildlife and white oak is probably the most important tree for wildlife . . . The acorns and the amount of insects it supports is just incredible.”

The other crucial factor is the forest it replaced.

Fast-growing white pines were long favored by landowners looking for relatively quick profits from harvests, Kelly said, and the plantation Headwaters inherited was “basically an agricultural system that was installed and replaced the native forest. It’s okay to remove that agricultural system and try to restore the natural forest.”

Habitats are “very site specific,” he said, and he hadn’t spent enough time on the property to detail the forage growing there or provide a precise list of species it supports.

But he could say that natural fires historically created openings in the wild landscape that were once far more common than they are now, and that these spaces generally attract a wide variety of wildlife, including bear, deer and turkey.

Reestablishing such a blend of habitats in Headwaters, which is dominated by densely canopied forest, was one of the logging operation’s main objectives, Wicker said.

“We’re not doing the same thing everywhere,” he said of the thinning and clearcutting. “We need the combination.”

And though he is neither a biologist nor a bird expert, he said, he can attest to the increased vitality of the recently cleared land.

For deer and turkey, he said, “the openings are great, especially the browse, the low vegetation they can get to.”

He pointed out a flitting hummingbird seeking nectar and paused to take in the soundtrack of constant songbird calls. The blossoms of black locusts had only recently dropped, he said, and blackberries and mountain laurels remained in robust bloom.

“I’m a hobby beekeeper and I would love to have my bees in here,” he said.

On a slope thinned by logging, tall hardwoods had spread among the pines, creating sheltered thickets for deer, he said. Oaks are key producers of “mast,” the fruits and seed crucial to sustaining wildlife, and have been crowded out by faster-growing species in dense forests throughout the southern Appalachians.

“They never make it to the midstory or the canopy because they don’t have the right sunlight conditions,” Wicker said.

White oaks are especially big deliverers of mast, he said, and clusters of these trees were planted among the shortleaf pines in the hopes that at least some of them will grow to maturity.

“The goal is for this to be a mixed shortleaf pine-oak forest,” he said.

Erosion was one of the main concerns of opponents to the clearcutting who said it would allow sediment from the exposed land to run into a nearby creek in Headwaters, which was established in 2018 partly, as the name implies, to protect sources of the East Fork of the French Broad River.

Wicker can’t guarantee that no soil was carried into the nearest stream. “I wasn’t out here 24/7,” he said.

But he did point to methods designed to prevent this from happening — wide wooded buffers left along waterways, logging slash that stabilizes the soil like mulch in yards, berms built by loggers to block the rapid flow of runoff.

Another objection: logging the land was all about generating revenue.

“Of course it makes money and we want it to make money,” Wicker said, but those earnings are poured back into the forest, bolstering old, erosion-prone forest roads, for example, and helping to pay for prescribed burns that will maintain openings in the growing oak-pine forest.

And certainly turning a profit wasn’t the primary goal. Headwater’s 10-year management plan makes no mention of this as an aim of timber harvests and instead emphasizes their role in creating “diverse habitat.”

To further demonstrate how this was accomplished, Wicker drove a few hundred yards up Glady Fork and walked from the road into the sunless ground under a remaining stand of the plantation.

Beneath his feet was a thick layer of dead pine needles and scattered cones and twigs. The understory growths of buckberry and ferns were sparse and isolated.

“There’s less cover for any wildlife species, way less browse as far as wildlife food and very few flowering plants,” he said. “It’s essentially only needle litter and I don’t know what eats needle litter.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Oak regeneration is often the reason given for silvicultural treatments such as clear-cutting old white pine stands. But the problem is oak regeneration is successful only where there are high numbers of oak sprouts and sufficient existing mature trees to supply mast and seed source for new sprouts. The current scientific literature also makes clear that the oak sprouts need to ALREADY EXIST because there are oaks in the canopy. You cannot plant enough oaks to ensure success. Then you need to manage the understory (fire) to ensure oak are not out-competed by other species such as beech, maple, or poplar. But, as is often the case, there is a secondary goal which is to increase deer (game) presence by creating early successional habitat (openings). Deer and oak regeneration are opposing goals. You see, oak sprouts are a favorite food of deer and they will overwhelm a planted oak population unless they are fenced out which of course isn't practical for a 50+ acre stand. "For deer and turkey, he said, “the openings are great, especially the browse, the low vegetation they can get to.” Herein lies the problem - you want oak to regenerate but you also want openings which attract deer and the deer browse the oaks that you just planted. You can have oak regeneration or you can have deer, but you can't have both.