Local Author Tells "America's Story" through Rosman Station's Past and Present

Craig Gralley says his newly released book about the history of the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute uncovers "one of the greatest mysteries of Western North Carolina.”

BREVARD — Images that are now so familiar — steady, overhead views of whirling storms bearing down on coastal communities — were unknown before 1969’s fearsome Hurricane Camille.

A National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) satellite in a fixed spot 22,000 miles above the Earth’s surface drew a bead on Camille and tracked its development from a tropical storm into a Category 5 hurricane.

NASA shared the photos with federal weather officials, allowing them to warn Mississippi residents in the storm’s path.

The technology was so new that many of these residents didn’t trust the forecast, “so lives were lost, but we saved a lot of people, too,” said Eugene “Joe” Collins, senior engineer for a geostationary satellite program once based at a NASA tracking station in Rosman.

Yes, that’s right, Rosman, or, actually, a remote former chunk of the Pisgah National Forest near the even smaller mountain community of Balsam Grove.

Reliable storm tracking, Zoom calls with loved ones during the Covid-19 pandemic, services such as DirecTV and even broadcasts of live sporting events from distant nations — all of them depend on technology the Rosman site was “instrumental” in developing, said Craig Gralley, author of the new book, Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute: An Untold History of Spacemen & Spies.

These advancements, especially as described to the author by the since-deceased Collins, are among the book’s highlights. But Gralley also reveals that the site may have served an equally vital role collecting intelligence for the secretive National Security Agency (NSA) during the 1980s and tells the inspiring story of its more recent evolution into a one-of-a-kind science education center.

As the “untold” part of the title suggests, much of this history was previously obscure, and the book, Gralley said in an interview this week in downtown Brevard, uncovers “one of the greatest mysteries of Western North Carolina.”

He knows the narrative will naturally resonate with people of that region, especially Transylvania County. “It’s a local story,” he said.

“But it’s also America’s story, because Rosman evolved and changed to face the greatest challenges our country faced — the space race, winning the Cold War, and now science education.”

Origins of the Book — and the Station

This combination of near and distant perspectives comes naturally to Gralley, a five-year resident of Transylvania who previously spent 34 years immersed in national policy, working first as an analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency and later as chief speechwriter for a series of CIA directors, including Robert Gates, who went on to serve as the U.S. Secretary of Defense.

A file he stumbled upon while working at the CIA led directly to the first book he wrote after retiring from the agency in 2013, the acclaimed 2019 historical novel, Hall of Mirrors — Virginia Hall: America’s Greatest Spy of WWII.

Less directly, his job also got him started on the book about the various incarnations of the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute (PARI).

He’d heard of NSA’s Rosman station during his time with the agency, and while driving up US 215 to start a hike with his wife, Janet, he passed a PARI sign featuring images of satellite dishes.

“We’re near Rosman,” he said, recalling his thoughts at the time. “The Rosman Research Station. Rosman Research Station is PARI . . . A light bulb went off.”

In a way he undersells the breadth of the forces that led to the original construction of the NASA station. They weren’t just national, but global. As he writes in Spacemen & Spies, the Soviet Union’s launch of the world’s first man-made satellite, Sputnik, left the US scrambling to fill a large gap in its knowledge of the largest of all subjects: space.

For example, Gralley writes, while the Soviet Union was able to launch Sputnik in 1957, Americans initially were unable to reliably track its orbit.

“We had so many questions about space science,” Gralley said, “about radiation belts around the earth, about the effects of gravity and the loss of gravity.”

Funding for NASA ballooned under President John F. Kennedy, who dramatically announced the goal of sending a human to the moon in 1962. The local station, bearing the unwieldy name Rosman Space Tracking and Data Acquisition Network (STADAN) Facility, opened a year later.

The federal investment included funds to build two “monstrously large” satellite dishes 85 feet in diameter, Gralley writes — so big their footers filled holes 90 feet deep, according to a local resident and longtime employee at the facility, Buster McCall, who told Gralley he had helped dig them.

The Whole Earth

Such antennae were crucial to its mission, tracking several different classes of low-orbiting satellites gathering data about, to name just two examples, solar activity and the Earth’s magnetic field.

But the station’s most lasting contributions may have been its work with Applications Technology Satellites (ATS), the first of which was launched in 1966.

Orbiting high above the equator and at a speed matching that of the Earth’s rotation, ATS craft were able to provide continuous views of 45 percent of the globe’s surface and serve as fixed reflectors capable of relaying messages between continents.

Workers at the station didn’t just collect data, but “commanded” the ATS program, Gralley said. “It was the premier East Coast facility for directing experimental satellite programs.”

And the program didn’t just lay the groundwork for future technology, but had a hand in some of its era’s landmark cultural events.

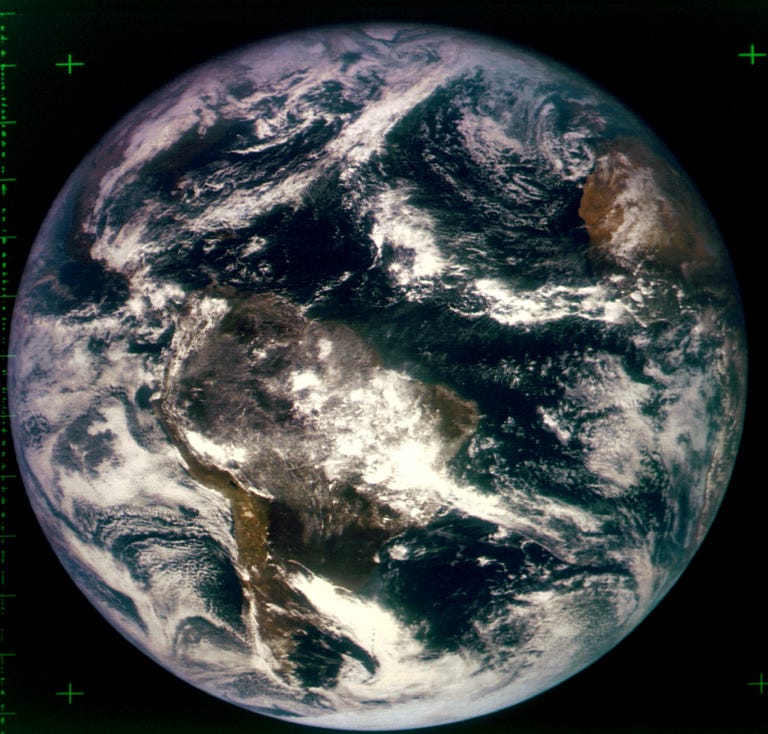

The first color image of the globe as a lonely blue ball, the one featured on the first cover of the aptly named Whole Earth Catalog and credited with helping propel the nascent environmental movement? It was captured at Rosman.

So were feeds from television cameras that provided, for example, the then-mind-bending live images of the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France.

Then there were the feel-good stories. High-orbiting satellites broadcast college-level educational programs to islands in the South Pacific and enabled an early and dramatic instance of telemedicine, relaying a doctor’s guidance for treating a hemorrhaging patient in a remote Alaskan village.

“They weren’t altruistic necessarily,” Gralley said of these achievements, but primarily served as technical challenges to Rosman engineers “trying to stretch the (ATS) capabilities and figure out, ‘Okay, how far out can we use these satellites?’ ”

NASA’s funding dwindled along with the nation’s interest in space travel during the 1970s, Gralley wrote, and the very technology the Rosman station had helped develop contributed to its demise. A new generation of satellites, he said, was increasingly able to take over its tracking mission.

So, the site fell into the hands of the Department of Defense (DoD) in 1981 for use by the NSA, an arm of the military “so secretive that its own employees call it ‘No Such Agency,’ ” Gralley writes.

The “Likely” Work of Spies

Renamed the Rosman Research Station, its grounds were patrolled by guards carrying automatic weapons. The DoD’s additions included panels of bullet-proof glass and “Building 14,” which housed a massive paper shredder staffed by an employee specifically recruited for his inability to read.

Still, Gralley was able to piece together its story from interviews with former employees identified only by their first names and last initials, as well as from the few publicly available sources.

He learned that as the US interest in Central America intensified, so did government investment into the Rosman station. It received about $200 million in new funding starting in 1985 and its workforce expanded from a peak of 260 employees during the NASA years to more than 400.

One research “breakthrough,” he said, came courtesy of the sales literature written after DoD moved on from the property. Just like a Realtor selling a home advertises its number of bedrooms, Gralley said, “when you sell a satellite facility you have a brochure that talks about the frequency of the antennas.”

Matching those frequencies with Congressional testimony about Soviet broadcast signals, he was able to pinpoint the station’s probable role in intercepting transmissions to Lourdes, Cuba, which he wrote was home of “Moscow’s largest, most sophisticated . . . collection and relay ground station outside of the USSR.”

“It is likely that the NSA used the Rosman Research Station to target the Soviet’s central communications center at Lourdes,” he writes.

His experience at the CIA gave him no special insight into such work, he said, but it did help him describe it in a way that could pass a review by federal officials before the book’s publication.

“That’s intelligence speak,” he said of the words such as “likely” that pepper this section of his book. “That is how you write an intelligence report because you don’t have confirmation.”

Easier to pin down was the local response to the secretive doings behind the site’s chain link fence, the creation of “myths” to fill the gaps, he wrote. Some Transylvania residents believed that Rosman, like the similarly named Roswell, New Mexico, was the site of an alien landing, others that the station covered a hidden underground city.

PARI

Another global event — the fall of the Iron Curtain — led the NSA to eventually abandon the site in 1996, leaving its future uncertain. The equipment that the government was unable to donate or dismantle represented a vast burden to just about any future owner of the site, which then covered a little more than 200 acres. That was especially true of perhaps the most likely recipient of the property, the US Forest Service, which would have required the restoration of the land to its natural state.

But then an avid amateur astronomer, J. Donald Cline, recognized the potential of the property and stepped up to save it. Cline, a retired Bell Labs engineer and entrepreneur, emerges as the hero of the last section of Spacemen & Spies. The book is dedicated to him and his recently deceased wife, Jo, and Gralley is donating his share of proceeds from its sales to PARI, the nonprofit Cline formed before taking over the site in 1999.

Cline, Gralley writes, has developed relationships with over 40 institutions, including the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and Duke and Clemson universities. Access to radio and optical telescopes that graduate students must often fight for is readily available at PARI.

But the site’s programs are also open to visitors with a more casual interest in science and to students of all ages — “from K to gray,” Gralley writes, quoting Cline.

“PARI summer camps represent a huge opportunity for students around the country,” Gralley said, but especially to local young people eligible for scholarships.

“That capability to to have hands-on use of this kind of scientific equipment is an enormous benefit to students in this area.”

By the way, he added, those “monstrously large” satellite dishes are still on the site, still in working order, still capable of generating funding to support the Institute’s mission.

“PARI is now positioning itself” to lease out these and other pieces of tracking and collection equipment, Gralley said, listing several potential customers, including private exploration companies such as SpaceX or maybe even NASA.

Which means, fittingly, PARI’s future could look a little like its illustrious past, he said. “It could come full circle.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com