Conditions in Rosman mobile home parks, a major provider of affordable housing, are not "pretty" but improving.

Owners say they are working hard to make repairs, but residents say they have lived with mold, insect infestations, leaks and inadequate heating, while housing advocates press for more protections.

ROSMAN — Bruce Presley, a slim, sideburned street preacher, opened the door to his single-wide mobile home — and to a view of the recent history of Rosman’s French Broad Mobile Home Parks.

Presley, 76, who can frequently be seen working the corner of Broad and Main streets in downtown Brevard, lives alone and pays his rent out of his Social Security check and with the help of a federal housing voucher.

Greg Kantor, whose family owns the park, said he regularly checks in on Presley to make sure he has money for groceries. And earlier this spring, a maintenance crew completed a renovation of Presley’s home that included a new roof and kitchen, as well as a much-needed cleaning.

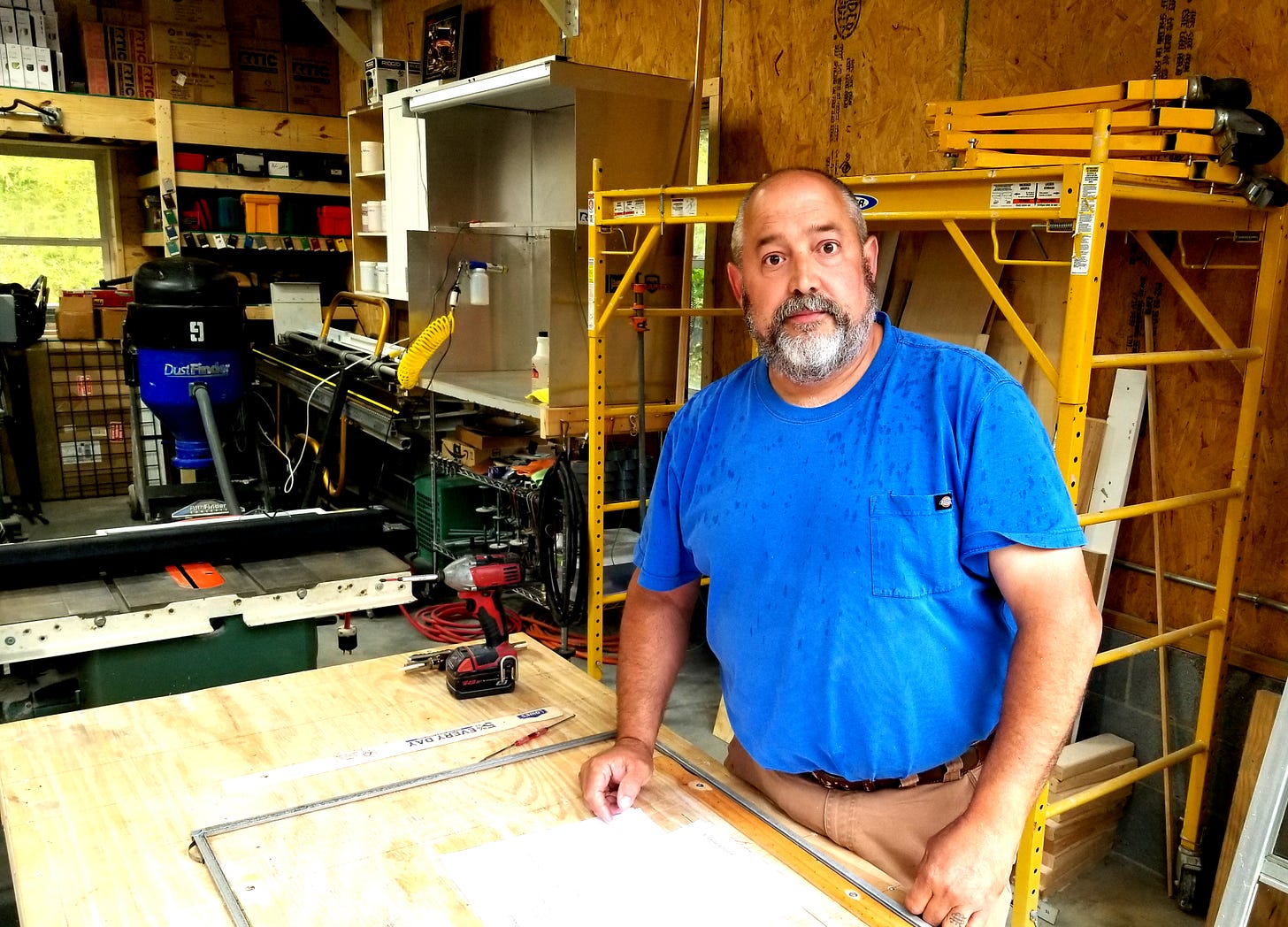

“I personally went in his bathroom and scrubbed every inch of it,” said Marcos Meilan, a close friend of the Kantors and part-owner of the park, who took over its maintenance a year ago.

Presley proudly showed off his home — the vintage television in wooden cabinet tuned to an episode of Wild Wild West, his collection of clocks and figurines purchased at thrift stores and Cracker Barrel, and, especially, his new sink and freshly painted walls.

“I look around and just want to shout and praise God for my brand-new home,” he said.

But before the fixes, he said, he lived nearly five years with mold, roaches and a haphazardly patched, chronically leaking roof.

“It was terrible, sir,” he said. “Terrible.”

Where Else Can They Go?

Transylvania County’s acute shortage of affordable housing raises an obvious question: As home and rental prices soar, and as waiting lists grow at income-restricted apartment complexes, where can the county’s low-income residents afford to live?

The answer is often the collection of mobile homes on a network of twisting gravel roads in or near Rosman, where many residents report the same trends as Presley — the sometimes-charitable but often-neglectful management of Kantor, a significant improvement in maintenance since the arrival of Meilan.

The Kantor family owns “north of 200” rental units in the county, said Greg Kantor, 45. About half of them, he said, are in the Rosman communities that go by variations of the name French Broad Mobile Home Park, which advertises itself on Facebook as the largest provider of affordable housing in Transylvania County.

The monthly, market-rate rents of between $500 and $750 are roughly half the countywide median found in Bowen National Research’s 2020 regional housing report and are intended to be “the cheapest in the county,” said Meilan, 50.

That makes these parks a magnet for residents getting by on federal assistance or earnings from the county’s many low-wage, service-sector jobs. The Rosman single wides also house 43 families — 24 percent of the county’s total — receiving Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers, said Sheryl Fortune, housing program director of Western Carolina Community Action (WCCA).

“Were it not for him,” she said, referring to Kantor, “where would they go?”

The living conditions at the parks reflect their position at the low end of the housing market, Meilan said.

“Is it a perfect, beautiful place? No, it’s a trailer park,” he said.

But Kantor, who handles the business side of the parks’ management, said he is a caring landlord who faces the extreme challenges of collecting rent and maintaining the property of low-income residents who in many cases struggle with mental health or/and substance abuse problems.

Since his arrival, Meilan said, the parks have worked hard to clean common areas and promptly make repairs, especially ones needed to maintain safe and sanitary conditions.

“Anything to do with water or heating or electricity we get on right away, usually in a day or two,” he said.

Unrepaired problems tend to be the unreported problems of residents who don’t want to draw attention to the money they owe — or just don’t care.

“I have a guy renting a trailer with six kids and two adults and they don’t lift a finger to do anything,” Meilan said.

Several residents agreed that Kantor is forgiving of unpaid rent and generally responsive to complaints, much more so since Meilan’s arrival, said tenants and Fortune. “It pretty much turned 180 degrees from what it was the last number of years,” she said.

But other tenants complained about widespread drug use and say they have lived for extended periods with deficiencies such as rotting floors, balky heating systems and leaking roofs and plumbing fixtures.

Older mobile homes also come with less pressing problems such as deteriorating insulation that can add hundreds of dollars annually to already strained housing budgets — and with the need for repeated repairs, said Sonya Flynn, senior housing specialist for WCCA, which conducts annual inspections of voucher-supplemented dwellings.

“Once a mobile home is past 10 or 15 years old, you’re going to find things that need to be fixed,” she said. “It’s just a given.”

Along with the dozen tenants who spoke about conditions were several more who declined to for fear that they would be evicted from the only housing they can afford. It’s an understandable sentiment considering the state’s toothless housing laws and the county’s shortage of affordable housing, said Robin Merrell, managing attorney for Pisgah Legal Services, which offers civil representation to indigent residents.

Merrell, who also serves as chairwoman of the board of the North Carolina Housing Coalition advocacy group, says local governments can help by passing enhanced minimum housing standards. They can also provide additional support for affordable housing projects that could ease the sky-high demand that gives landlords leverage over tenants.

When residents do find affordable housing in a market as tight as Transylvania’s, she said, “it’s in their best interest to keep it, and that can mean not rocking the boat, because the landlord knows there will be a whole lot more people to rent to as soon as that tenant is out.”

The Owners’ View

Rosman Mayor Brian Shelton said mobile homes first started to appear along Old Rosman Highway in the 1980s and for many years the largest of these was owned by Johnny Rogers, who served as town mayor from 1997 to 2006.

County property records show French Broad Mobile Home Park LLC — with Kantor’s father, Charles, listed as a company officer — bought Rogers’ property for $400,000 in 2005.

The park contained 30 to 40 homes at the time, Greg Kantor said. The family’s companies, county records show, have since bought several nearby tracts and have received permits to install 74 additional or replacement mobile homes in or near Rosman, including 10 last year.

Between 2006 and 2018, a town ordinance prohibited the installation of mobile homes more than 10 years old, and most of the units on that original property were manufactured in the 1990s or early 2000s.

The oldest home, however, dates back to 1969 and, along with a handful more built in the 1970s, carries an assessed value of $1,000, while the total taxable value of the 67 mobile homes on the parcel is $248,000.

But this glimpse into the companies’ business doesn’t begin to provide a complete picture, Meilan and Greg Kantor said.

The roads, which tend to wash out after heavy rains, need regular, expensive regrading, Meilan said, and since his arrival he has sealed 95 roofs and renovated 13 mobile homes at a cost of about $10,000 each.

He recently rented an excavator to remove discarded, sodden mattresses and couches, and he spends hundreds of dollars weekly in tipping fees and other cleanup costs. He has bought a standing stock of water heaters and toilets to have on hand as replacements — all for tenants who routinely fall behind in their payments.

“If we evicted everybody who owes us money, nobody would be left in the park,” Meilan said, adding, when pressed about this statement, that it is only a slight exaggeration.

The French Broad Mobile Home Park companies have filed dozens of claims over the years to evict tenants and collect unpaid bills, including 26 in 2020, according to court records, which also show that the parks have collected not a single dollar of the back rent awarded in these judgments.

Eviction is a last resort, Meilan said, and one that has mostly been unavailable since the implementation of a (recently overturned) federal restriction on evictions after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. And Kantor said his goal is to keep tenants in his park, not kick them out.

“If they will communicate with me (about money owed), I bend over backwards to help,” he said, and described himself as the benevolent manager of a refuge for otherwise unwanted tenants whom he considers “family.”

The parks don’t “discriminate” against residents with histories of drug arrests or mental illness, Meilan said. Kantor distributes toys to the park’s children at Christmas and is sometimes charitable to a fault, Meilan said, which is why he has allowed people desperate for shelter to move into homes not ready for habitation.

“I think I provide a stepping stone for people to move on to better things, to find a house, to buy properties and live the American Dream,” Kantor said. “I can honestly tell you, I try to make the world a better place.”

Stepping Stone

There’s some truth to this portrayal of the park and Kantor’s management, said Brian Peacock, a 45-year-old father of two, as he planted a terraced vegetable garden in the slope behind his home on a recent afternoon.

He described Kantor as responsive to complaints and felt confident that that a crew would repair a recently broken window, covered by plywood, that he said he had not yet reported. Peacock, a construction worker, and his wife, a manager at Dollar General, could probably afford to pay the high rents at the apartments they looked at after arriving in Transylvania two years ago, he said.

But the $740 monthly rent they pay for their mobile home has allowed them to progress towards their goal of buying property.

“All I care about right now is the land, and maybe later I can build a house on it myself,” he said.

David McCall, 32, an experienced chef who makes $12.50 an hour working at a Cook Out restaurant, said Kantor was sympathetic when he missed payments as his hours were cut during the pandemic.

“I got $2,600 behind and he still didn’t threaten to kick me out,” said McCall, who pays $750 a month in rent for a three-bedroom mobile home that he shares with his unemployed father and four children.

“Greg was a really nice guy, taking what I could give him,” said McCall, who said he used Covid-19 relief payments to clear his debt. “He really understands the common folk.”

Another resident, Vicky Garcia, 43, said the park had recently repaired the roof on a mobile home she shares with her longtime partner, Dan Hall, and that she has seen little evidence of the criminal activity and drug use reported by other residents.

“I love my neighbors,” she said.

Roaches, Drugs, Mold

But even some generally content residents report unsatisfactory living conditions.

Peacock said his furnace is so inefficient that he warms his home with space heaters and that a hole in his bathroom floor was covered with a sheet of linoleum. He has also paid for an exterminator, he said, in a fruitless effort to control a chronic roach infestation, one of the tenants’ most common complaints.

“The roaches are bad and it doesn’t have anything to do with cleanliness,” he said, sweeping his arm to indicate the park as a whole. “They’re just there.”

Hall, 57, said the crew working on the roof caused damage to the ceiling that has not been repaired and that the floor is settling in what appears to be one of the park’s older homes.

“It needs to be taken down and moved out of here,” he said.

Tia Shetters, 34, who has lived at French Broad for two years, said she recently lost her job as a customer service representative for Amazon, partly because the company would not make mental health accommodations after the sudden death in July of the father of the youngest two of her four children.

She now gets by on their Social Security survivor benefits, she said, more than half of which is consumed by her $740 rent, and she is so concerned about criminal activity in the park that she sometimes carries a gun and doesn’t let her children out of her sight.

“Your kids are supposed to be safe in their home and mine are far from it,” she said.

As she spoke, a homeless man who has served prison time for drug charges, Chevus Griffin, was temporarily living in a tent served by an extension cord that ran from the home next to Shetters’. Through mid-April, the Transylvania County Sheriff’s deputies reported making 97 trips to the Rosman parks in 2021, including to serve warrants and to respond to calls for matters ranging from “shots fired” to “animal complaints.”

“This is very definitely a problem area for our guys,” said Chief Deputy Eddie Gunter. “We probably answer no less than four or five calls a week up there for something.”

Meilan said he has recently talked to deputies about ways to address drug use in the park, but Shetters said that’s not the only problem.

Having previously been evicted from French Broad and having spent time living on the street, she is grateful for any housing, she said. But a broken furnace the first winter of her return forced her to warm the mobile home with space heaters, Shetters said, and she pointed out an ongoing problem she has told Kantor about repeatedly, pressing her foot into a puddle of water at the base of her toilet.

“It’s been leaking for two months and now the floor is getting soft,” she said.

The clearest pictures, literally, of the state of the homes before Meilan took control of maintenance were posted on the Facebook page of a former resident, Shannon Bentley. Her mother still lives in the park and reports that crews are more attentive now.

But images that she shared with NewBeat show walls and ceilings soaked from roof leaks, decaying floors, and carpet matted with mold.

The fixes were long-delayed and temporary, said Bentley, who received a Housing Choice Voucher that subjected her home to annual inspections.

Park management, she wrote in a Facebook message, “didn’t fix anything until the day before the inspection and even then it would be a Band-Aid.”

The Flimsy Safety Net

There are some provisions in place to ensure adequate living conditions for voucher recipients, but almost nothing for tenants who pay out of pocket, housing advocates said.

Dwellings occupied by voucher holders are inspected before tenants move in and then annually to ensure that they are “decent, safe and sanitary,” Flynn said.

“Nowhere does it say new. Nowhere does it say pretty,” she said.

Renters who live in uninspected homes, and who say their complaints are more likely to be ignored because of it (an accusation Kantor called “ludicrous”), are supposed to be supported by a similar standard in North Carolina law.

The statute requires that landlords provide “fit and habitable” housing, said Merrell, of Pisgah Legal, but it does not adequately define that standard, and it is mostly enforced by lawsuits, “which take resources and time that most low-income people don’t have.”

Mike Owen, Transylvania’s code enforcement administrator, said that his department only inspects permitted repairs and new construction; it does not address living conditions in existing housing. Neither does the county’s Public Health Department, said Environmental Health Supervisor Jim Boyer, who cited as an obstacle to such inspections the county’s lack of a minimum housing law.

That points to one of the main benefits of the ordinances passed by local governments including Buncombe County and the cities of Asheville and Brevard, said Ben Many, another Pisgah Legal attorney. Such laws usually designate a staffer or department to enforce them.

Both Transylvania and Rosman have passed mobile home ordinances, but these focus on issues such as roads, utility service and the space between units needed for fire safety. The age limit on homes in the Rosman code was removed, said Shelton, the mayor, because the town was advised it was not legally defensible.

Neither government has passed a law covering minimum housing standards or is considering it.

“Of course commissioners would look at anything regarding the health of the citizens,” said County Commission Chairman Jason Chappell, but “nobody has ever approached commissioners with that.”

Shelton said that the cost of assigning a staffer to inspect homes and respond to tenant complaints is far beyond the reach of a town with a budget of less than $1 million.

“We don’t have the resources,” he said.

A Different Park?

Meilan and Kantor said they are working hard to provide decent housing without oversight.

Kantor rejects the notion that his family ever neglected maintenance, saying that he is doing what he has always done, providing shelter for people who desperately need it.

“I can’t tell you how many phone calls I get from people who say, ‘I need a place and I need it yesterday.’ I talked to someone the other day who said he’d been couch-surfing for a year,” he said. “There’s such a void for housing and I really feel like I’m doing the best I can.”

But Meilan said that as Charles Kantor, now in his 70s, grew older and his health declined, and with Greg Kantor splitting his time between Florida and North Carolina, “a lot of stuff got pushed to the side.”

Since he arrived “I’ve been going in and getting after it full-throttle,” he said. “Our goal is, in the next couple of years, it’s going to be a whole different park.”

Marcos Meilan is a wonderful guy! Good for you on tackling those jobs.

Good morning Dan. I look forward to all your thorough articles and tackling of the issues of our community. Keep up your fantastic reporting!