Can Raybow's Expansion Set a Trend for BioScience Growth in Transylvania County?

Economic development leaders say the growth in the pharmaceutical company's business of "making molecules" may bring more, high-tech industry to the county.

By Dan DeWitt

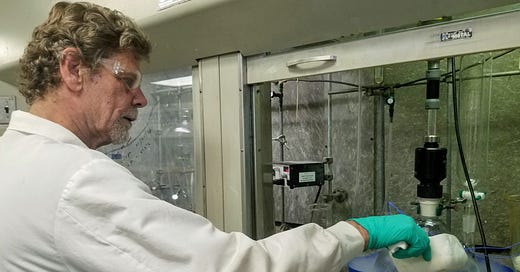

BREVARD — Though Peter Barker looks every bit of what he is — a highly trained chemist working for an international pharmaceutical company — he says he’s really just cooking, just refining a recipe.

Tall and goateed, wearing a lab coat and safety glasses, he hovered over a round-bottomed glass flask rotating in a bubbling, steaming bath of alcohol and dry ice at Raybow PharmaScience’s Brevard lab.

This project started with mixing general amounts of chemical ingredients, Barker said, “a cup of flour and a cup of sugar.”

Now he’s honing in on the final product. “We’re at the stage where we’re saying three-quarters of a cup of flour,” he said, “and one-and-a-half cups of sugar.”

The equivalent of the taste test will be conducted in the company’s analytical lab, which measures the chemical components in prospective and completed products, typically ingredients sold to pharmaceutical companies.

Before these compounds can be served — aka used in human testing — they are cooked up in a federal Food and Drug Administration-approved Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) room.

This is a super-clean, climate-controlled chamber where the process of brewing chemicals is scrupulously measured and documented — and where the comparison between lab and home kitchen breaks down completely.

“If you’re cooking and you screw up, you end up with something that doesn’t taste good,” said Roger Frisbee, co-president of RayBow USA. “If we screw up, we can make people sick or worse.”

The High-Tech Business of Raybow

So no matter how hard Raybow’s scientists try to make their work understandable, make it sound like stuff the rest of us might do every day, in reality it is pure, high-tech, high-stakes industry, which is clear as soon as you walk into the Raybow USA building on a wooded lot east of downtown.

In the front offices, scientists huddle over indecipherable graphs displayed on large-screened computer monitors. White-coated chemists such as Barker work behind them in a glassed-in lab, monitoring test tubes and flasks, consulting lengthy diagrams of chemical reactions grease-penciled on transparent panels above their work stations.

To the left is the analytics room, where the centerpiece is a bell-shaped stainless-steel device that uses powerful magnets to blast chemicals into measurable components, and where tables are stacked with sleek, white machines costing $50,000 apiece.

The GMP room, to the right, is occupied by workers in protective gowns and is so thoroughly ventilated that to open even the outermost of its sealing doors is to be met with a powerful blast of air.

And when Frisbee is not downplaying the complexity of the lab’s job with the standard cooking metaphor, he uses a phrase that suggests a mastery of the building blocks of the universe: “making molecules.”

This advanced work all takes place in an unlikely setting — the squat, 11,000-square-foot former dress factory that serves as the U.S. headquarters of China-based Raybow PharmaScience.

The planned $15.8 million expansion, which will quadruple both the size of the workforce and its floor space, might be the start of another ambitious job in an unexpected location: promoting small, remote Transylvania County as a hub of life-science enterprise, adding sorely needed, well-paid research and manufacturing jobs to the local service-based economy.

Along with Gaia Herbs and Pisgah Labs, which, like Raybow, serves the pharmaceutical industry, “we already have a pretty decent biotech cluster,” said Josh Hallingse, who as executive director of the Transylvania Economic Alliance helped secure the deal for Raybow’s expansion with $464,000 in county tax incentives.

Figuring in the growth of Gaia and the investment into Pisgah Labs, represented by its 2017 purchase by India-based Ipca Laboratories, Hallingse said, “to me it’s not a huge reach to think that this sector will continue to expand over time.”

How Raybow Fits In

Frisbee explained his lab’s role by projecting an image showing a series of chemical reactions. He didn’t name the compounds — he never names names — but said the important thing is the process.

At the top is the starting ingredient, which can be any one of a variety of easily available compounds.

In some cases, it’s the byproduct of a widely distributed drug such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), he said, and “we could potentially start with finger polish remover and make almost anything.”

At the bottom is the target product, the chemical his clients hope to manufacture.

In between are the steps of mixing, heating and/or cooling required to get from start to finish. The example Frisbee displayed mapped out seven steps. Others take as few as three or as many as 30.

Raybow not only can sell this process, demonstrating to clients how to manufacture arcane and expensive ingredients from common and cheap ones. It can also sell the target ingredient itself. Or at least some of it.

At its current size, the Brevard lab might only be able to provide enough of the chemical to see the client through the initial stages of drug testing.

In the rare cases where the required quantities are small, the company is certified by the FDA to serve as a long-term supplier.

“Ophthalmics are a good example,” Frisbee said, referring to eye medications. “World demand is in the hundreds of grams.”

The Expansion

This limited production capacity is one reason Frisbee, 62, and Raybow USA co-president Peter Newsome, 59, started thinking about expansion, and, eventually, Raybow.

They formed PharmAgra Labs in 1999 and moved to the current location in 2002. Daunted by the financial risk of dramatically growing the company so near retirement, they shopped their operation around to larger firms capable of backing their expansion before selling it to Raybow in November of 2019.

Frisbee and Newsome chose the company despite the potential for disruption due to the mounting concern over the aggressive trading practices of China, which Frisbee compared to the passing worries, decades ago, of the economic threat of Japan.

Key to their decision, they said, is the size of the company, which employs 1,500 workers worldwide, and its firm footing in markets in Europe, China and the U.S.

“The U.S. and China have the greatest growth potential,” Frisbee said.

This was confirmed soon after the purchase, with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Frisbee, true to form, declined to say which ingredients they made for which companies. But he did say his lab worked for industry giants developing components of antiviral medications and vaccines, and that they put in a lot of long hours and seven-day work weeks.

“We were very busy, and we had some very short time lines,” Frisbee said. “I think we are all proud of that work.”

Transylvania and Life Sciences

Outside of the building, he pointed to the parking lot, which will be occupied by the planned 30,000-square-foot expansion of the lab, to be built in two phases.

More lab capacity will mean more demand for highly trained workers such as Barker, who has a doctorate in chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley and 40 years of experience in the industry. It's the kind of knowledge needed to develop the series of reactions that “build molecules,” Frisbee said.

On the other side of the building, in a newly cleared lot, will be the pilot plant, so named because it carries out on a limited scale the processes that clients will use for mass production. This will create more jobs for technicians, not all of whom need advanced degrees.

Building a bigger pool of such workers is one way that industrial hubs are established, Hallingse said. Employees can learn the skills needed to safely and accurately manufacture these chemicals by working in related jobs at Pisgah Labs, Gaia or maybe even local breweries, Hallingse said.

More demand can justify programs at Blue Ridge Community College or other nearby institutions, Hallingse said, that will offer “more two- and four-year degrees for technicians and operators.”

But the terms of Raybow’s incentive program requires that it creates 74 jobs paying an average of at least $76,500 per year, more than twice the median annual salary in Transylvania.

That will mean recruiting highly educated workers, who will form another growing pool of workers, and another path for Transylvania to grow as a life-science hub.

Just as Frisbee, who formerly worked at Pisgah Labs, recognized a market and built a company to serve it, some of these other scientists might identify niches that need to be filled.

This model has been established in regions anchored by large research universities, Hallingse said, “places like Boston or Raleigh where you have large concentrations of PHD-level and masters-level scientists.”

It could happen here on a smaller scale, several community boosters have said, for the same reason Transylvania became a retirement hub. It’s a nice place to live.

Barker, 69, is a California native who previously worked in regions known for pharmaceutical research, New Jersey and, most recently, Ann Arbor, Mich.

When Newsome approached him about coming to Raybow five years ago, “he told me to Google ‘Transylvania’ and ‘land of waterfalls,’ Barker said.

“I was struck by the scenic beauty of the area,” he said. “I was pretty much blown away . . . That’s what sold me on this specific area.”

https://www.raybow.com/