Building "Forever" Homes: Habitat, other Nonprofits, Tackle Affordable Housing Crisis

A coalition of local churches and charitable organizations is working to add affordable and workforce residences, with rapidly growing Transylvania Habitat for Humanity leading the way.

ROSMAN — Mackenzie Galloway’s Transylvania County housing story starts on the usual, discouraging path.

Ownership seemed out of the question due to the county’s sky-high home prices and the limited chances for Galloway, 23, and her husband, Levi, 22, to build credit.

And never mind that Levi Galloway has a good job, installing heating and air conditioning systems; the couple couldn’t come close to affording the $1,500 average monthly rent for apartments large enough for them and their toddler son, Sawyer, Mackenzie Galloway said.

Though they’ve been lucky to be able to live with her husband’s parents, she said, it was hard to imagine how they could find a place of their own.

Not, at least, until they reached an agreement with Transylvania Habitat for Humanity that requires the Galloways to make house payments — set at no more than 30 percent of their income, about $1,150 monthly— and contribute a total of 400 hours of “sweat equity.”

They have both worked at the organization’s ReStore thrift outlet in Pisgah Forest. Levi Galloway helped with the framing of a home in Habitat’s Don Ross Acres in Rosman. And last week, Mackenzie Galloway vacuumed up dust so a crew of volunteers could begin laying flooring.

In return, hopefully before Christmas, the house “will be ours,” said Mackenzie Galloway, a stay-at-home mother, after shutting off the industrial vacuum cleaner for a brief interview.

“It’s going to be where my son grows up,” she said. “It’s going to be our forever home.”

The happy ending to the Galloways’ story isn’t an isolated case. It’s a sign of the potential for Habitat for Humanity and other local nonprofits to shift the housing narrative for dozens of low-to-moderate income Transylvania residents.

To be sure, these groups can’t solve the county’s vast shortage of affordable and workforce housing. But they are providing a needed supplement to local government efforts, many of which are admittedly incremental and geared for long-term results.

One of these organizations, Habitat, has recently initiated a new outreach program to recruit volunteers from local churches, and this year launched a “critical repair” program that has helped the organization dramatically increase the number of county residents it serves.

With its recent acquisition of an 8.1-acre property near Brevard, Habitat has brought its total holdings of land for future projects in the county to about 19 acres.

At least two Brevard churches, meanwhile, are eyeing future affordable or workforce developments on their own vacant parcels.

And though the Sharing House poverty assistance organization is still working on its affordable housing plans, these could be advanced by the organization’s purchase of a one-acre parcel near its headquarters in the city’s Rosenwald neighborhood.

Representatives from all these organizations are meeting monthly as part of the year-old Brevard/Transylvania Housing Coalition, an informal group formed with the recognition that government action alone cannot address the county’s acute shortage of reasonably priced homes and apartments.

“I feel like the Housing Coalition has really gotten traction and there are important organizations and government people at the table,” said Sharing House Executive Director Shelly Webb, one of the Coalition's founders.

“We are advocating for more support from all aspects of the community for housing because it truly is a crisis.”

The Growth of Habitat

Though broad-based collaboration is the goal, at this point the work of one organization clearly stands out.

“The big advance of the past year has been the growth of Habitat,” Webb said.

It’s actually been about three years coming, said Angie Hunter, who has served as the organization’s executive director since October of 2019.

Revenue plunged a few months later, with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, she said, as did the number of available volunteers and even residents seeking the group’s services.

“Covid was really not a good year for us,” Hunter said.

Told that the Sharing House was able to build a nest egg from donations that surged after the pandemic but have since flattened, Hunter illustrated Habitat’s post-Covid revenue trend with a dramatic upward sweep of her right hand.

“Ours has been more like this,” she said.

Since the end of fiscal year 2020-21, the proceeds from ReStore have more than doubled to about $915,000.

That’s enough to cover the group’s payroll and operating expenses, Hunter said, “so when we go to the community to ask for donations for materials, we can say all that money goes for construction.”

Though the total amount of grants and contributions received by the group fluctuates annually due to one-time infusions of funds, it climbed from about $163,000 in the fiscal year that ended in June of 2020, to about $738,000 last fiscal year.

That number does not include increased proceeds from home sales, which — due to a change in Habitat’s agreement with lenders — are now distributed to the group after closing rather than over the life of 30-year mortgages.

Also above and beyond the revenue number from last fiscal year: the pledge of a $550,000 grant from Dogwood Health Foundation that will allow it to start work on planned projects in Rosenwald.

With more money coming in, the organization has increased its full-time staff from 10 to 18. This, in turn, has allowed more outreach to volunteers, whose total number of contributed hours has climbed about 50 percent compared to pre-Covid levels.

This trend should continue with the launch, earlier this fall, of the Faith Build program that enlisted more than 15 new recruits from two Brevard churches, St. Phillips Episcopal and Brevard-Davidson River Presbyterian.

Also new this year: the critical repair program designed to allow low-to-moderate income-residents stay in their homes.

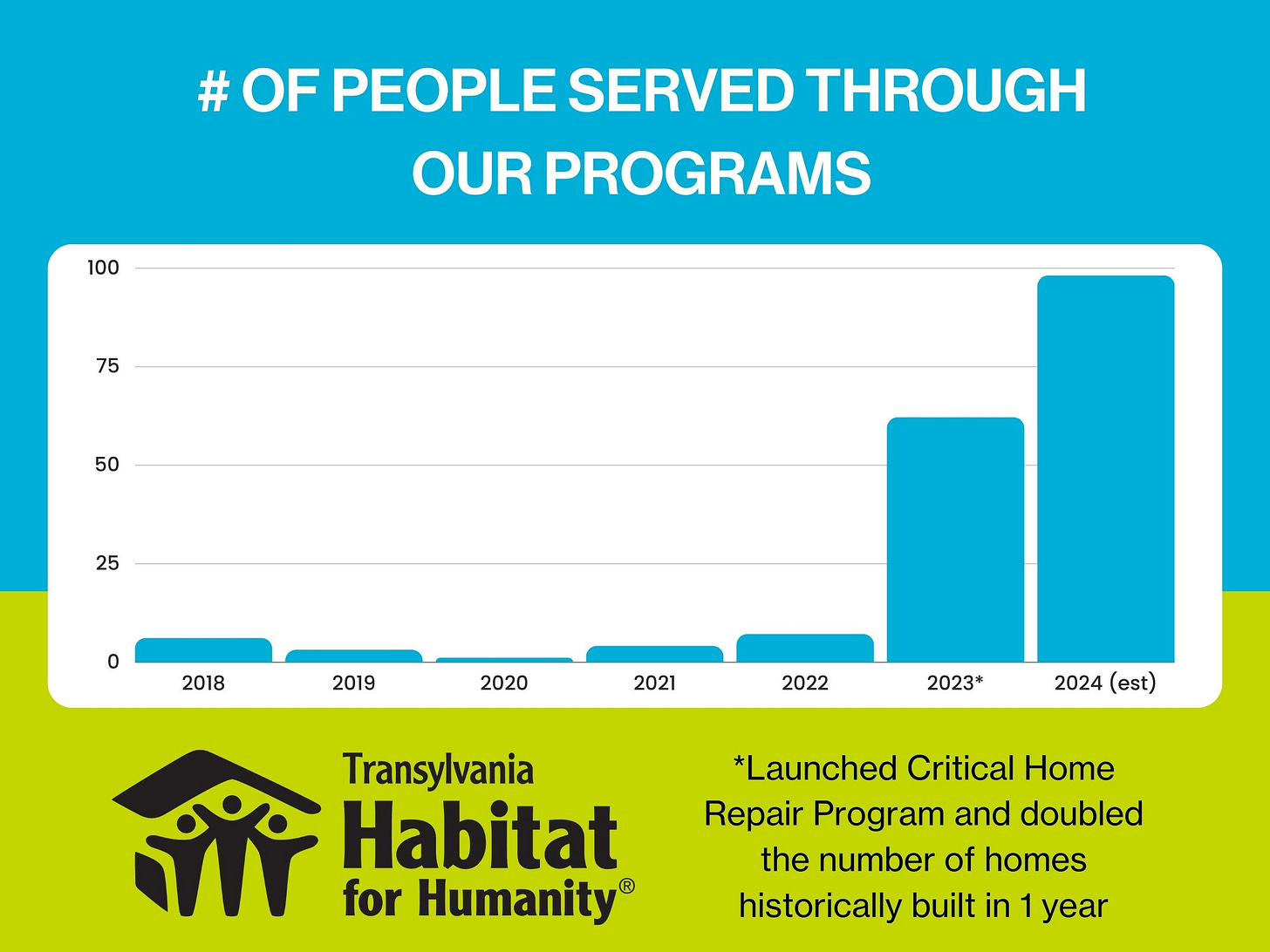

By the end of the year, Habitat expects to complete about 60 essential upgrades such as roof and heating-system replacements, propelling the surge in the total number of impacted residents documented in the graph below.

“This year we’ve seen a huge growth in our organization,” Hunter said. “It’s a really exciting time.”

The Importance of Land

But it’s also just a start, Hunter acknowledged.

Habitat, for all its accomplishments, is on track to complete five homes this year.

Meanwhile, even before the local post-Covid real estate boom, about 800 low-to-moderate-income Transylvania families were in need of housing, according to a July report from an arm of the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s School of Government — a study that also documented the seemingly intractable roots of the crisis.

Half of Transylvania’s workers are employed in industries such as retail that pay an average of less than $40,000 per year, according to the report from the School’s Development Finance Initiative (DFI), while the average price of a new home more than doubled between 2016 and 2022 to $633,000.

But the study also suggested a crucial role for nonprofits in addressing one of the most daunting obstacles to addressing the county’s housing shortage — its dearth of developable parcels.

DFI looked at three lots in the city considered promising locations of future affordable or workforce housing projects. Their total area amounted to 16.3 acres and they all carry significant obstacles to development ranging from steep slopes to unwilling sellers.

Habitat, Sharing House and two area churches, on the other hand, own a half-dozen parcels totaling about 25 acres. And all these groups have at least tentative plans to reserve these properties for reasonably priced housing.

Habitat’s holdings include 8.6 acres on See Off Mountain Road where the organization plans to build single-family homes — sometime after it takes on projects in Rosenwald.

“Rosenwald will be our next step,” Hunter said.

On the two parcels it owns there, Habitat plans to both add affordable units and push back on the gentrification that, longtime residents say, has undermined the character of the historically Black neighborhood and led to an exodus of long-time residents.

Habitat will build a five-bedroom home on one of its Rosenwald properties. On the other lot, the organization will assist occupants of two existing homes and, on the parcel’s remaining land, break with its long-time pattern of building exclusively single-family homes.

It will instead construct a fourplex, Hunter said, in recognition that the lack of land in Transylvania demands increased density to address the affordable crisis.

And though the organization has no firm plans for its large, recently acquired property on Meadow Lane, it may also look at building more than the 33 residential units the property’s current zoning allows.

Habitat will work with nearby residents, she said, and avoid disrupting the atmosphere of a neighborhood dominated by single-family homes.

But “we want to go with as high a density as possible,” she said. “We’re not opposed to town homes.”

Churches and Sharing House

Sharing House’s plans for the one-acre lot adjacent to its current offices are also in the early stages, said Cara Bradshaw, the group’s community impact director.

The organization’s leaders are charting a long-range path forward that, at this point, could lead in several directions, including a renovation of its 40-year-headquarters and/or an expansion of its scope of services to affordable housing.

Which is what prompted Sharing House to jump at the chance to buy the property for $625,000, a deal expected to close this week.

The parcel is now the site of two small rental homes, and Bradshaw said the group will “work with existing tenants . . . and keep it affordable for them. We’re looking into making some repairs. We want to be good landlords.”

Considering that the land also borders The Haven long-term homeless shelter, the wooded central section of the property may be an ideal site for “transitional housing,” offering stability and support for residents as they seek permanent homes.

They could access existing Sharing House services such as food, clothing and emergency financial assistance, Bradshaw said. This model would also call for a portion of residents’ rent to be set aside for future expenses including deposits on apartments or down payments on new homes.

“Some of their rent would be going into a nest egg for them,” Bradshaw said. “Whatever we do we want to make sure that people are building equity as renters.”

Brevard-Davidson River Presbyterian owns an even more promising, 4.7-acre property near its sanctuary in downtown Brevard. Pastor Keith Thompson said he is not ready to discuss the church’s plans for the land, other than to say that it is exploring its use for affordable or workforce housing.

“There is stuff happening. Meetings are continuing,” he said. “Feasibility studies are continuing.”

Brevard First United Methodist Church, on the other hand, is firmly committed to building housing for teachers on the site of the former Rosman United Methodist Church.

The Brevard congregation, which controls the property, sought to honor the disbanded church’s “legacy” of service to Rosman, said Veranita Alvord, the Brevard church’s pastor. And it heard from school officials about an obvious way to help — addressing the lack of affordable housing that is a major impediment to recruiting new teachers.

The plan is to ultimately build two to four small houses on the land near Rosman High School, Alvord said, which will require both future fundraising on the part of the church and the kind of collaboration that Sharing House’s Webb advocates.

Sharing House recently secured a grant to pay for an engineering study that will determine the property’s capacity, Alvord said. The church will start by constructing a single home, she said, and “we hope that once we build one we can find other nonprofits and private sources to build some others.”

“This for us, is a low-hanging fruit,” she said. “It’s not huge, but it’s an effort to do what we can do to help get the ball rolling.”

Housing Help for Workers

The need to provide housing for teachers points to an essential truth about the affordable housing crisis in Transylvania.

Though much is often made of the difference between low-cost “affordable” housing and mid-range “workforce” housing, that distinction tends to evaporate in a county where wages are as low as those documented in the DFI report.

In Transylvania, most residents meeting income requirements to qualify for affordable housing are in the workforce.

“Workforce and affordable housing — those terms in this economy are interchangeable,” Thompson said.

Case in point, outgoing Brevard City Council member Maurice Jones, the father of four young children who works as a merchandising manager for Lowe’s.

To qualify for Habitat assistance, prospective homeowners can make no more than 80 percent of the area median income, Hunter said. For a family of Jones’ size in Transylvania, that threshold stands a $65,000 per year, according to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Yes, Jones has solid employment, he said, but his wife doesn’t work outside the home partly because of his oldest son’s special needs, and “my income is the only income for a family of six.”

They now live in a two-bedroom house. The five-bedroom home that Habitat plans for his family will be built on land that Jones grew up on and that his mother donated to the organization.

“It will mean freedom,” Jones said, “because right now we're just living on top of each other.”

The Need for More

In one way, Jones represents a major part of the Habitat success story.

“I think it has a lot to do with the myths about Habitat being busted,” Hunter said.

Among these is that it provides free houses to indigent families, she said, while the nonprofit actually tailors payments to the incomes of mostly working homeowners. But clearing up such false impressions means “we have a lot more people requesting our services,” she said.

Which in turn means that it must continue to grow, must find more revenue and enlist more volunteers.

More people, in other words, like Mike Wallace, a member of the St. Phillips congregation who said he typically volunteers for Habitat on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

But there he was last Thursday morning, carrying boxes of flooring into the future Galloway home and then proceeding, unprompted, to unfold a step ladder and begin painting the fine line between a wall and ceiling.

He acquired a range of construction skills as a long-time supervisor of a golf course in Connecticut, he said. “I have the ability and I feel if the Lord gave me that gift I should use it.

He encourages others to do the same, even if their skills are more limited than his and they available only occasionally.

The work is flexible, he said. He likes the camaraderie of the crew. And especially because he knows the acute need for housing in the county, he has enjoyed the satisfaction of bringing 10-unit Don Ross Acres to near completion, watching the houses take shape, seeing deserving families like the Galloways move in and make these houses their homes.

“This is my ninth house. To see a community come together, with kids, it’s very rewarding,” he said. “We’ve built a little neighborhood here.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

Habitat is an amazing ministry. It gives people dedicated to diligence in working their way consistently and helping them

with financial

skills while they put in their “sweat equity”.

Great article Dan!

I would love that