Brevard Resident and Acclaimed Historian Unmasks Klansman, the Legacy of Segregation

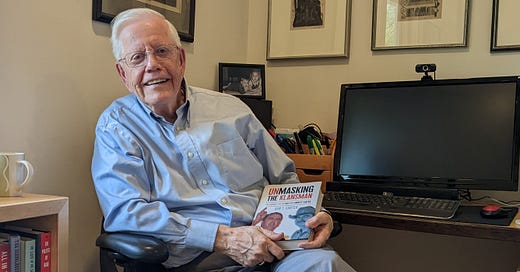

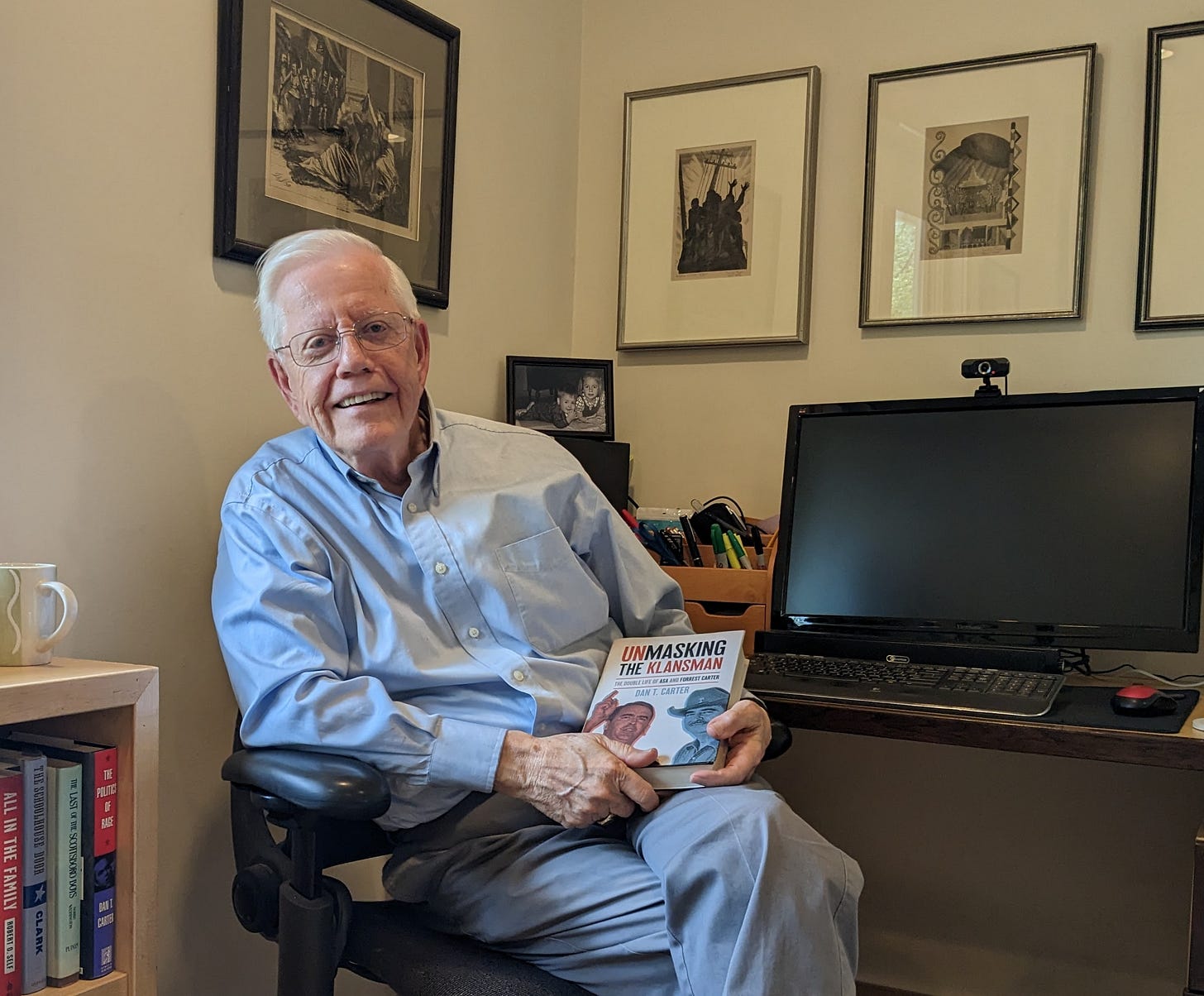

Dan T. Carter, called "one of the greatest" historians of the South, has published a new book that completes his life's work of revealing the lasting damage of the region's segregation era.

BREVARD — To see why Dan T. Carter is one of the nation’s most admired historians of the 20th century South, look at this single sentence in his new book, Unmasking the Klansman: The Double Life of Asa and Forrest Carter:

“While a fellow Klansman held the kerosene lamp, Floyd severed the testicles of Judge Edward Arone and placed them in a Dixie paper cup.”

It’s the product of Dan Carter’s typically relentless research. Though the hours he spent poring over the case’s trial transcripts sometimes left him feeling “queasy,” he said, he kept at it because the details he unearthed allowed him to capture the essence of his subject, the dehumanization of the man’s white supremacist beliefs.

That “Judge” is not a title, it’s a first name, a cultural clue that Dan Carter — who grew up in the segregated South and has written about it for more than 50 years — is uniquely qualified to decipher. Working-class African Americans such as Arone were often given grand-sounding names to “subtly mock” a system that failed to grant them basic respect, Carter writes.

Then there’s the unadorned language. Passing judgment is not just unnecessary — the brutality of the action speaks for itself, Carter said — it would interfere with his main goal, which is to reveal.

“You don’t have to agree with people, you don’t even have to fully empathize with people,” he said during a two-hour interview last week in the small, elegantly furnished home in Brevard he shares with his wife, Jane, whom he calls his first and best editor.

“But at least understand what’s going on in their heads.”

It’s been his life’s work, understanding the segregated South and sharing his findings as a history professor at schools such as Atlanta’s Emory University and as the author of seven books.

His first, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, was a rare doctoral thesis gripping enough to receive a special citation from the Mystery Writers of America and scholarly enough to be awarded a 1970 Bancroft Prize as a distinguished work of history.

The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics, published in 1996, is not just the definitive biography of the former Alabama governor; it served as the basis of PBS’s award-winning documentary, George Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire.

“I have an Emmy in there if you want to see it,” Carter said casually, sitting in his office and nodding in the direction of a neighboring room.

So Carter is a national figure. Ask his fellow historians about him and you hear words such as “foremost,” and “outstanding,” descriptions like “great detective” and “master storyteller.”

“Dan Carter is one of the greatest historians to ever write about the South,” Princeton University history professor Kevin M. Kruse wrote in an email. He called Scottsboro “a fearless work” and the Wallace biography “one of the most insightful and beautifully written accounts of a major political figure anywhere.”

But Carter is also a loyal and engaged resident of Transylvania County, where he has owned property since the 1990s and lived full-time since his retirement from teaching in 2010.

There’s the unusual cultural vibrancy for a city its size, he said, but it also “has that small-town thing. As Jane says, you can’t really walk too much downtown because you’re not really walking. You’re stopping and talking.”

The “Fountainhead”

Dan Carter listed several reasons not to write about Asa Carter.

He’s a “right-wing nut from the 1950s who had a very limited following,” Dan Carter said.

As depicted in the book, he was also a thoroughly loathsome character, an extreme and violent white nationalist even by the standards of segregation-era Alabama. He bullied family members, lied routinely, and not only left dirty work such as attacking Arone to his Ku Klux Klan followers, but bilked them out of their membership fees.

The prospect of immersion into such darkness, Dan Carter wrote in the book’s introduction, prompted his wife to ask, “ ‘Do you really want to spend years getting inside the skin of Asa Carter?’ ”

Yes, he ultimately decided. Because despite Asa Carter’s obscurity, he left an outsized and lasting legacy.

Forced to work behind the scenes due to his toxic reputation, Asa Carter helped guide Wallace’s transformation from a young liberal to the nation’s leading spokesman of white supremacy.

When Wallace, in his infamous 1963 inaugural address, pledged to stand for “segregation now . . . segregation tomorrow . . . segregation forever,” he wasn’t stating long-held beliefs. He was channeling Asa Carter, who wrote the speech after being locked in a hotel room with a carton of Pall Malls and two bottles of Jack Daniels by a campaign staffer.

That was another of Asa Carter’s compelling traits: He could really write, which in turn created an irresistible narrative hook for his biographer — Asa Carter’s use of this gift to con the nation.

Facing a dwindling market for racist screeds, he disappeared from public view in 1972 and reemerged with a first name stolen from his lifelong hero — the unrepentant Confederate general and founder of the Reconstruction-era Klan, Nathan Bedford Forrest — and a charismatic persona stolen from the Cherokee Indians.

It was as the tanned, slimmed-down and purportedly Native American author Forrest Carter that he wrote The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales, later made into one of the most profitable and acclaimed Westerns of the 1970s. A “memoir” about Forrest Carter’s fabricated Cherokee upbringing, The Education of Little Tree, became a posthumous New York Times number-one best seller in 1991.

A different Carter, but the same instinct for the power of a false narrative, which leads to the final reason the historian Carter (no relation) was determined to finish a book he first imagined more than 30 years ago.

Asa Carter’s reach was limited to the audiences of tiny radio stations and his self-published magazine. Contemporary hard-right commentators and politicians are seldom as nakedly racist as Carter, but they can spread similarly divisive and inaccurate messages across the country by way of social media and Fox News.

“I was trying to show that all this has a background and a history we have to be aware of,” Dan Carter said. “In some ways the fountainhead was in the 1950s and ‘60s.”

The Lure of Hateful Politics

He knows the seductive power of lies such as white superiority, he said, because he was seduced himself.

“It’s a reminder of how easy it is to live in that world,” he said. “It’s the water you swim in.”

So besides being a biography and a cultural history, Unmasked is a personal book, interwoven with Dan Carter’s memories of growing up on a tobacco farm near the eastern South Carolina town of Florence — stories that also came up a lot in his interview.

Their main theme: his amazement at both the dominance of an idea that was so clearly wrong and the courage of the handful of residents willing to point that out.

The principal of Carter’s school, he writes, held an assembly to announce that the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled, in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, that segregation is unconstitutional. He urged calm and pointedly called black people not “nigras” but “negroes,” making it sound like “knee-grows,” Carter writes, “a correct pronunciation I had only heard on radio and in films.”

When the principal later ran for school superintendent, “he wanted us to see integration not as a ‘problem’ but as a challenge,” Carter writes at the end of the section. “He lost by a two-to-one margin.”

There were a handful of similar figures in Florence, including the editor of the local paper and an older cousin of Carter’s who sometimes went off for a walk when other family members started talking about race.

“It just reminds me how lonely it was for people who stuck their heads above the parapet,” he said.

On the other hand, he said, he remembers watching the The Ed Sullivan Show with the family of a girlfriend who made a mildly approving comment about one of the guests, the African-American singer Johnny Mathis.

“Her father exploded. ‘If I ever hear another word like that out of your mouth about this n—---- or any other n—---, you are out of the house,’ and she was a high school senior,” Carter said, shaking his head at the memory.

“I thought, ‘My god, my parents are segregationists, but they ain’t segregationists like this.’ ”

At least, he said, they didn’t believe in gratuitous humiliation, the crushing weight of which he realized when he saw it briefly lifted.

He recalls his father, a contractor, giving directions to a black truck driver delivering a load of lumber. He called him, “Joe,” and the driver told young Dan Carter, “ ‘You know, your daddy is the only white person who doesn’t call me ‘boy,’ who calls me by name,’ ” Carter said. “I thought, that really is a hell of a thing, that that simple decency is something people aren’t willing to give.”

The Quest

The origins of Unmasked can be traced to a much earlier unmasking, which is another reason that writing the book became a personal mission.

In 1991, as Dan Carter was researching the Wallace book and Little Tree was climbing the best-seller lists, he wrote a column in the New York Times revealing that Forrest was really Asa, not a Cherokee from the hills of Tennessee but a county boy-turned-white nationalist from northern Alabama.

The backlash came from both the book’s publisher and Carter’s surviving friends and family members, none of whom agreed to be interviewed for Unmasked.

Undeterred, Dan Carter started researching the project after the publication of the Wallace book and the airing of the subsequent documentary. By 2007, he had completed several chapters.

But without personal accounts, it read like a doctoral dissertation, he said, and not like the page-turner about Scottsboro he wrote for his actual dissertation at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

“It was flat,” he said.

One breakthrough came years later when the producers of a documentary about Asa Carter generously allowed him to view outtakes of their interviews. Another came from a longtime reporter for the Anniston (Ala.) Star, Fred Burger, who had also planned a book on Asa Carter.

The two bonded over their shared interest, and Dan Carter was stunned when Burger died suddenly at age 68 in 2018 — and stunned again when Burger’s brother donated about 200 hours of his taped interviews to the Public Library of Anniston-Calhoun County, saying that is what Fred Burger would have wanted.

“That was another reason I plunged back into it,” Dan Carter said of the book, which is dedicated to Burger.

It created a lot of work at a time when Dan Carter could have been enjoying retirement. He could have been pursuing his hobby, building furniture. He could have traveled with Jane and the families of his adult children. “I have a bucket list,” he said.

He instead spent hundreds of hours listening to tapes, reading trial transcripts, and, of course, writing, which was always hard for him and only got harder as he aged, said Carter, 82.

But he had one more figure of the American South to understand, one more gap to fill in the big story he has been writing since he was in graduate school.

“No one better dissects the dynamics of race and southern politics from the 1930s through . . . Wallace to (Richard) Nixon and (his) Southern Strategy and right up to (Donald) Trump,” Tony Badger, a retired professor of American History at England’s Cambridge University, wrote in an email about Carter.

“When I turned in the last page, I thought, ‘Was this really worth it?’ ” Carter said. “But it would have haunted me until the day I died if I had left it unfinished . . . That is really what drove me at the end. I think this is a story that needs to be told.”

Email: brevardnewsbeat@gmail.com

BRAVO, Dan! Dan Carter is a wonderful person, compelling historian, and so deserving of this terrific article you've written about him and his new book on Asa Carter. As a much younger reader, I was very moved by The Education of Little Tree. Dan's full story about him adds so much more to the profound puzzlement and horror I felt when I first heard about the complexities of that man. I'm so grateful you for writing this column!

Wow!! Just Wow.